Christine Neill and Saul Schwartz

The Biden administration has announced plans for student loan forgiveness. It would make little sense for Canada to follow suit.

The Biden administration has just announced plans to forgive $10,000 of student loan debt for all borrowers who earn below US$125,000 ($250,000 for couples). Anyone who came from a low-income family and who received a Pell grant will have US$20,000 forgiven. Inevitably, there is talk of similar debt relief in Canada.

We think a targeted and generous debt-relief program is good for former students who are struggling to repay their loans. But, Canada already has such a program — one focused on those who are struggling. Broad-based loan forgiveness would disproportionately benefit families in the upper half of the income distribution.

Borrowers who run into difficulty should be the priority

It is certainly true that young people can take some time to find their feet in the labour market. Even in good times, some student loan borrowers will leave school and not be able to start repaying their student loans immediately. More of them have trouble when unemployment rates are high, particularly in a recession or, as we have seen, in a pandemic. There are good reasons for governments to have a student loan system that provides insurance against such bad outcomes.

Canada’s Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) provides targeted reductions in repayments to borrowers whose income is so low that the required student loan payments are likely to cause hardship. Under RAP, individuals earning less than $25,000 per year pay nothing on the federal portion of their student loans and pay nothing on the provincial portion of their loans in most provinces. No interest gets added to borrowers’ loans while they are enrolled in RAP.

Compared with other debt-relief programs in other jurisdictions, RAP is fairly generous[1] and is scheduled to become more generous if — as promised in the 2022 federal budget — the zero-payment threshold for individuals rises from $25,000 to $40,000. For those with incomes above the zero-payment threshold, an affordable payment is calculated depending on family income and size.[2]

Roughly 23 per cent of all borrowers in repayment at the end of 2018-19 were enrolled in RAP and 85 per cent of those enrolled were in the zero-payment range.[3]By contrast, broad-based student loan forgiveness along U.S. lines is not targeted at those having difficulty. To be sure, it would help those who are struggling. But it would also reduce the debts of many who are able to repay.

According to Statistics Canada’s 2019 Survey of Financial Security, about two-thirds of Canadian student loans are owed by individuals who live in families in the upper half of the income distribution.[4] Forgiving (in whole or in part) student loan debt would benefit richer families more than poor families.

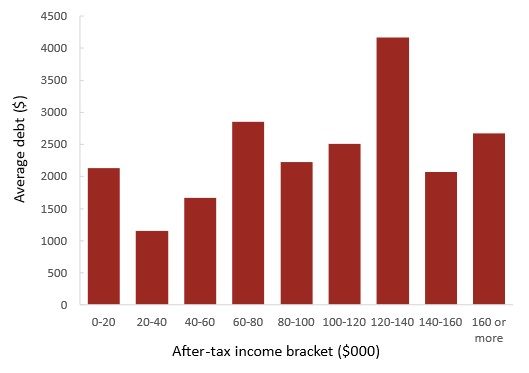

Figure 1: Average student loan debt per household, by after-tax income group (all Canadian households)

In general, the average amount owing is higher for families in higher income brackets (Figure 1). So broad-based student debt forgiveness in Canada would transfer resources to the group who were able to go to college or university – often in more expensive programs or for a longer time – and who borrowed to do so.

Ongoing debt forgiveness is already doing the job

RAP builds in regular and ongoing debt forgiveness. For those who have been on RAP for less than 60 months, or are less than 10 years out of school (i.e., in Stage 1 of RAP), no nominal interest accumulates. That means the value of the debt decreases every month in real terms. When interest rates are low, this debt forgiveness is relatively unimportant, but when interest rates and inflation are higher, it matters much more. For those in Stage 2 of RAP, the debt forgiveness is more explicit. The government figures out how much borrowers would have to pay each month to have all their debt paid off by the time they have been out of school for 15 years. But borrowers are required to pay only an affordable amount each month – usually zero – and the rest is forgiven. So, the dollar value of the debt falls month after month until nothing is left owing 15 years after leaving school. Around six per cent of all borrowers in repayment are in Stage 2.

An interest moratorium for all borrowers — like the one now in place until March 2023 for federal loans — mostly benefits those with higher incomes. Those with low income are eligible for RAP and need not pay interest.

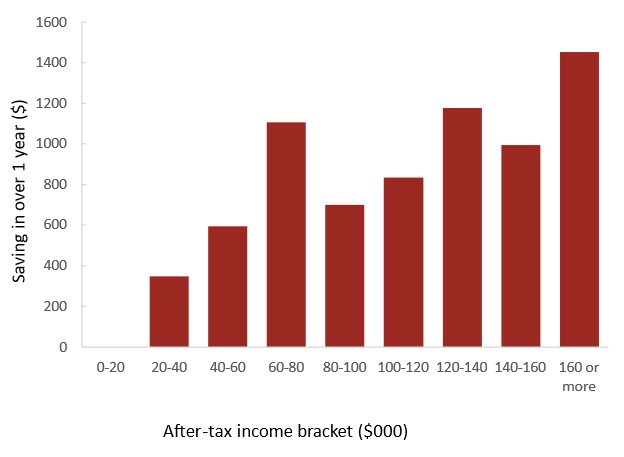

Figure 2: Average savings from interest moratorium relative to status quo without a moratorium (including RAP), for households with student loan debt, by income

Figure 2 shows a rough simulation of how much borrowers might have saved per year because of the interest moratorium. Anyone with household income below $20,000, and at least half of those with income between $20,000 and $40,000, could have been enrolled in RAP and would pay no interest, with or without the moratorium. Those with some debt and household incomes above $160,000, by contrast, would have paid close to $1,400 in interest on average without a moratorium.[5] The cost to the federal government of its interest moratorium is roughly $350 million per year.[6]

Broad-based debt forgiveness is quite costly

If Canada were to forgive up to $10,000 in any form of student loan debt for all households with some current debt, the cost would be around $16 billion. Restricting that to households with after-tax income of $120,000 or less would lower the cost to $12.5 billion.[7] It would dramatically cut the number of households with outstanding debt – by 900,000 out of the roughly of the two million households that owe some student loan debt.

These figures would be rather smaller if only the federal government acted and forgave only the debt owing to it, because a large proportion of student debt in Canada is owed to the provinces.

Conclusion

We are not saying that one-off loan forgiveness is a bad thing. Governments are often quick to help out troubled businesses deemed to be important enough that failure would lead to widespread hardship for laid-off workers. There are definitely borrowers straining under the burden of repaying their student loans or who are stressed because they are not repaying those loans. The point is that we already have a system in place to help those who are struggling and we have many other uses — affordable housing, gaps in health-care provision, food insecurity – for the money that might otherwise be spent on further loan forgiveness.

Loan forgiveness for all has one attractive feature, albeit not an economic one. It is politically attractive, providing benefits to a wide swath of the middle class.[8]

For Canada, there are better ways of improving the way we address the very real problems of borrowers who are struggling with repayment. The government has already moved to increase RAP’s zero-payment threshold from its current low level. Other options include:

- Make RAP the default, rather than requiring re-application every six months;

- Make it easier for defaulters to rehabilitate their loans;

- Lower the rate at which the affordable payment increases with income;

- Allow the discharge of student loans in bankruptcy without the seven-year rule;

- Trigger an automatic interest moratorium when unemployment rates are high enough (a Canadian version of the proposed Sahm rule could be used here);

To sum up, one-off debt forgiveness makes little sense in Canada where student debt levels are much the same in dollar terms as they have been for 20 years; have gotten lower over time as a percentage of income; and where there is already a robust if imperfect system to protect those struggling with repayment. The money spent on further loan forgiveness would be better spent on other priorities.

Christine Neill is an associate professor of economics at Wilfrid Laurier University, specializing in education and post-secondary financial aid policies.

Christine Neill is an associate professor of economics at Wilfrid Laurier University, specializing in education and post-secondary financial aid policies.

Saul Schwartz is a professor at the School of Public Policy & Administration at Carleton University, specializing in social policy, the economics of education and labour economics.

Saul Schwartz is a professor at the School of Public Policy & Administration at Carleton University, specializing in social policy, the economics of education and labour economics.

References

Neill, Christine. 2022. Reducing the Burden of Student Loan Repayment: A Canada-US Comparison. In Schwartz, Saul (ed.), Oppressed by Debt. Routledge: New York

[1] In other programs, nominal interest still accrues for those enrolled. Other programs also tend to have payments that increase with income without a cap. But in Canada, no one pays more than a fixed mortgage-style payment. RAP ensures that any debt owed 15 years after leaving school is forgiven; no other program has as short a debt forgiveness horizon. On the negative side, Canada’s current zero-payment threshold is relatively low – $25,000 is below the annual income one would earn working full-time at a minimum wage. Payments also increase very quickly with income under RAP – over a short range, by more than 50 cents for every additional dollar of gross income. See Neill (2022) for further detail.

[2] The RAP “zero-payment” threshold rises with family size. The increased zero-payment threshold for individuals foreseen in Budget 2022 will lead to increases in the family-specific thresholds as well.

[3] Authors’ calculations from Table 1.6.1 (p.28) and Table 1.3.1 (p. 22) of CFSA Statistical Review for 2020-2021 available here. We have chosen to report the pre-pandemic percentages here but the percentages are similar for 2020-21.

[4] The SFS public-use files do not allow us to distinguish between debt owed to governments or to private sources such as chartered banks. The vast majority, however, is owed to federal or provincial governments. Private debt is likely disproportionately owed by those who studied in high-income fields such as law or medicine.

[5] Figure 2 assumes that all debt reported in the SFS receives interest relief; however, not all eligible borrowers are enrolled in RAP, so Figure 2 is something of an overestimate.

[6] The $350 million figure assumes an interest rate of 4.5 per cent; a stock of $11.6 billion in federal student loan debt in repayment as of the end of June 2020; and that $4 billion of the $11.6 billion would have been owed by RAP recipients. It also assumes that interest accumulating on delinquent and defaulted loans is eventually recovered. Assuming non-repayment of that interest as well, the cost would be closer to $200 million. Higher interest rates are increasing these costs.

[7] Based on the household level student loan estimates from the 2019 SFS.

[8] For an assessment of the political impact of U.S. student loan forgiveness, see https://www.npr.org/2022/08/26/1119283353/student-loans-biden-democrats

Susan Dynarski, a prominent U.S. economist, explains why she supports broad-based loan forgiveness in the U.S.