Frances Woolley

Recently, a proposal to end essentially all pandemic-related restrictions on the activities of young and healthy people has attracted significant attention and criticism. This commentary presents data which shed light on the question of whether (public health effects set entirely aside) implementing this type of proposal could actually meaningfully boost Canada’s economic performance. It shows that because young people earn only a small overall share of total income in the economy, there are unlikely to be substantial benefits for the overall economy from loosening or eliminating the restrictions on younger Canadians.

The Great Barrington Declaration argues against universal lock-downs. The authors of the declaration call for young and healthy people to be allowed to return to normal life, with “focused protection” limited to the elderly and other people at high risk of severe outcomes from contracting COVID-19. The declaration reads, in part:

“Those who are not vulnerable should immediately be allowed to resume life as normal. Simple hygiene measures, such as hand washing and staying home when sick should be practiced by everyone to reduce the herd immunity threshold. Schools and universities should be open for in-person teaching. Extracurricular activities, such as sports, should be resumed. Young low-risk adults should work normally, rather than from home. Restaurants and other businesses should open. Arts, music, sport and other cultural activities should resume. People who are more at risk may participate if they wish, while society as a whole enjoys the protection conferred upon the vulnerable by those who have built up herd immunity.”

I am going to set aside the epidemiological merits of the Declaration – while recognizing that they are important in and of themselves, and for the economy’s performance – and instead ask: how much of an economic impact would a targeted easing up of restrictions have?

To answer that question, we need to figure out how much spending power is in the hands of “young low-risk adults”, and how much is in the hands of “people who are more at risk.” COVID-19 risk depends upon a variety of factors, including sex, blood-type, body mass index, and so on. However age appears to be a key risk factor – 40 to 49 year olds in the US are 10 times more likely to die from COVID than people between 18 and 29. The odds of COVID death for people aged 50 to 64 years are 30 times the odds for individuals between the ages of 18 and 29. We can, therefore, arrive at an approximate estimate of the economic effects of loosening restrictions for low-risk individuals by measuring younger people’s aggregate income and purchasing power.

Canada Revenue Agency’s Taxation Statistics are one source of information on the distribution of after-tax income by age. These report the total amount of income declared by every Canadian taxfiler, broken down into five year age categories, as well as the taxes paid. They are not a perfect measure of after-tax income. They only include personal income reported for income tax purposes, and not corporate income. Also, the taxation statistics do not include a measure of after-tax income, so I estimated it by calculating net income minus total taxes paid. Moreover, these numbers are from 2016, so are somewhat out of date. But they serve to make a point.

First, even if young low-risk adults can work normally, it won’t make much difference to the amount of money spent on restaurants, arts, music, sports and other cultural activities, because young low-risk adults don’t earn much money. Many are in school or just starting out in the labour market. Young people’s wages are relatively low, and their unemployment rates are relatively high.

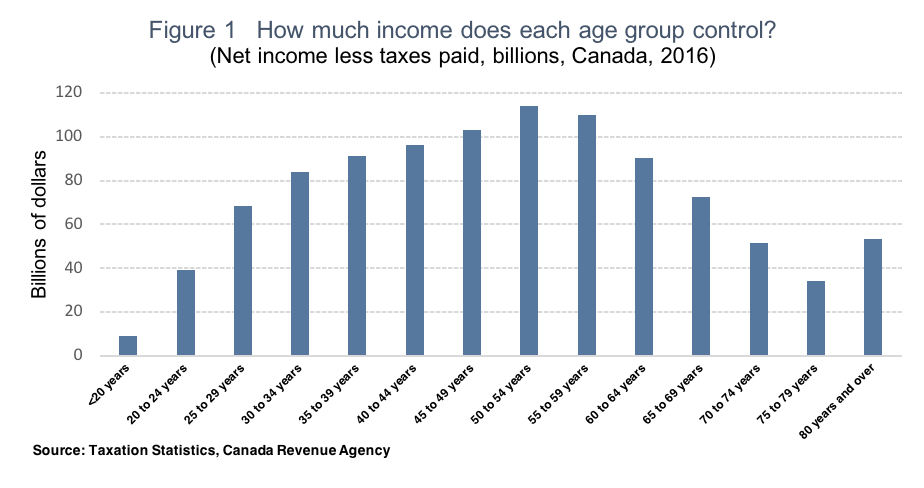

In 2016, the age group that controlled the most economic resources was 50 to 54 year olds: the after-tax income of all Canadians in that age group added up to a total of $114 billion. The next highest earning age group 55 to 59 year olds, raking in a collective $110 billion after taxes, followed by 45 to 49 year olds. This should come as no surprise. These cohorts are large. In 2016, people aged 50 to 54 were the single largest age group in Canada, followed by people 55 to 59. Moreover, people in their 50s and 40s are at the peak of their earning potential.

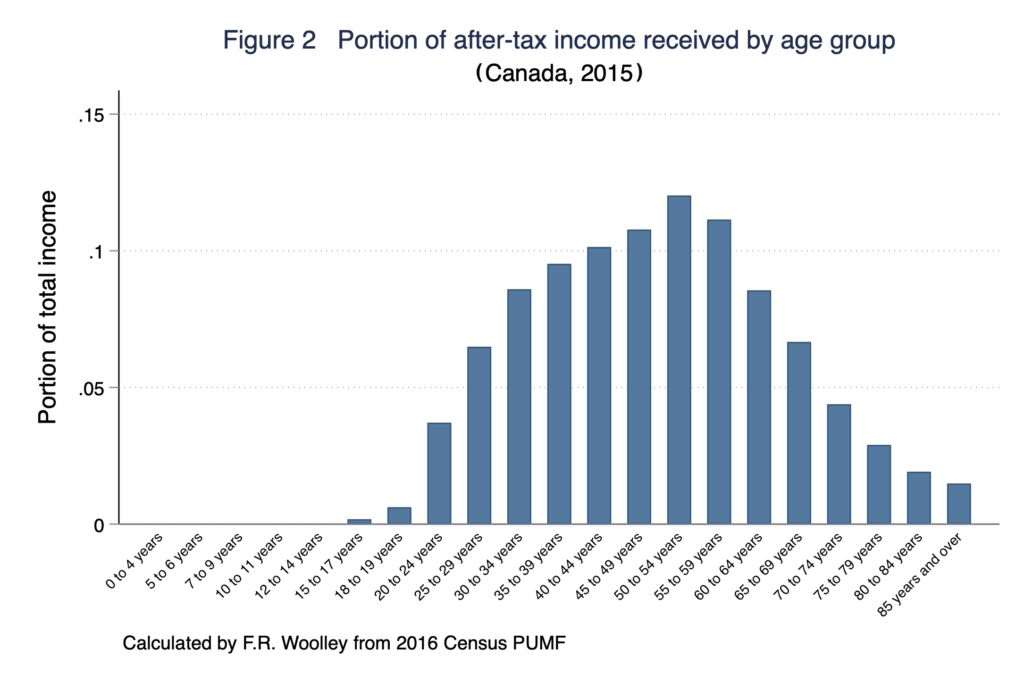

Since CRA’s Taxation Statistics are not a perfect measure of after-tax income, I double-checked the analysis using the 2016 Census Public Use Microdata File (PUMF). The same pattern holds – roughly 10% of after-tax income is in the hands of people under 30, and the age group with the greatest after-tax income is 50-54 year olds:

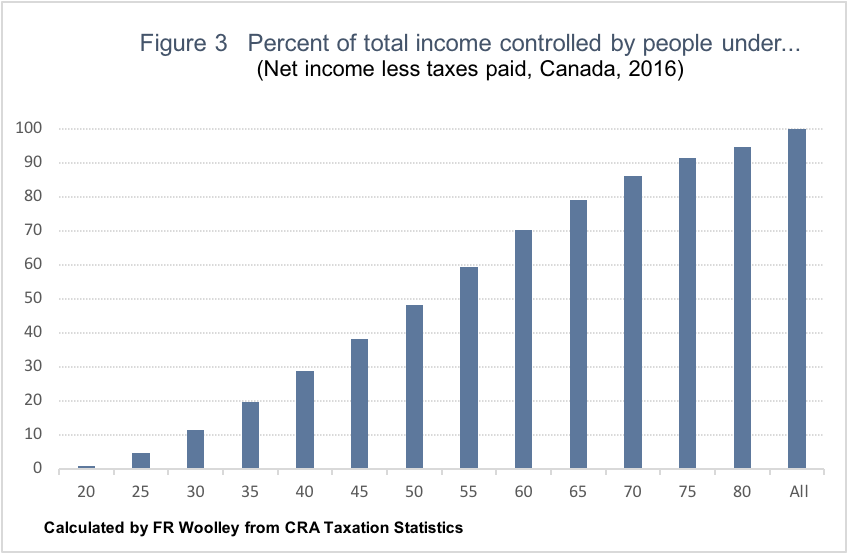

Figure 3 presents the Canada Revenue Agency data slightly differently. It shows the percentage of total income received by people under the ages of 20, 30, and so on. For example, the graph shows that people under the age of 20, who reported a total of $9 billion of after-tax income in 2016, accounted for less than 1 percent of the total after-tax income reported that year. People under the age of 30 accounted for 11 percent of the reported after-tax income. Less than half of after-tax income was received by people under the age of 50. The majority of income was received by people 50 and over.

These data are from 2016, so are slightly dated – but the aging of the baby boomers would be expected to push the bulk of purchasing power even higher up the age distribution.

It could be argued that people in their 20s and 30s don’t earn that much money, but they’re the ones who keep the economy going by buying homes, cars, and consumer durables. Yet this argument actually undermines the idea that loosening economic and social restrictions on young people would resuscitate the ailing sectors of Canada’s economy. The housing market is on fire right now. Car sales are strong, as are sales of consumer durables. It’s the service sector that’s hurting – plays, music, restaurants, museums, art galleries, and so on. And, generally speaking, it’s middle-aged people who have disposable income to spend on these services.

The evidence in this post suggests that following the advice of the “Great Barrington Declaration” and eliminating nearly all restrictions on the activity of younger people would have only a limited impact on the health of the Canadian economy. Young people simply don’t make enough money. What’s more, a number of the sectors of the economy that are driven by younger people are thriving right now. These facts should inform any public discussion about the possible costs and benefits of implementing the advice of the Great Barrington Declaration.

This commentary is a modified version of a blog post originally posted by Worthwhile Canadian Initiative