Michael Smart

The scale and speed of the COVID-19 recession and the fiscal policy response has been remarkable. This commentary shows what has happened since the beginning of the pandemic and discusses the implications for future fiscal policy choices in Canada.

As Canada looks hopefully to a future after the COVID-19 crisis, it is a good time to reflect also on the massive economic experiment that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has undertaken. Never before has Ottawa spent so much – or borrowed so much – to support workers, businesses, and the broader economy in a recession.

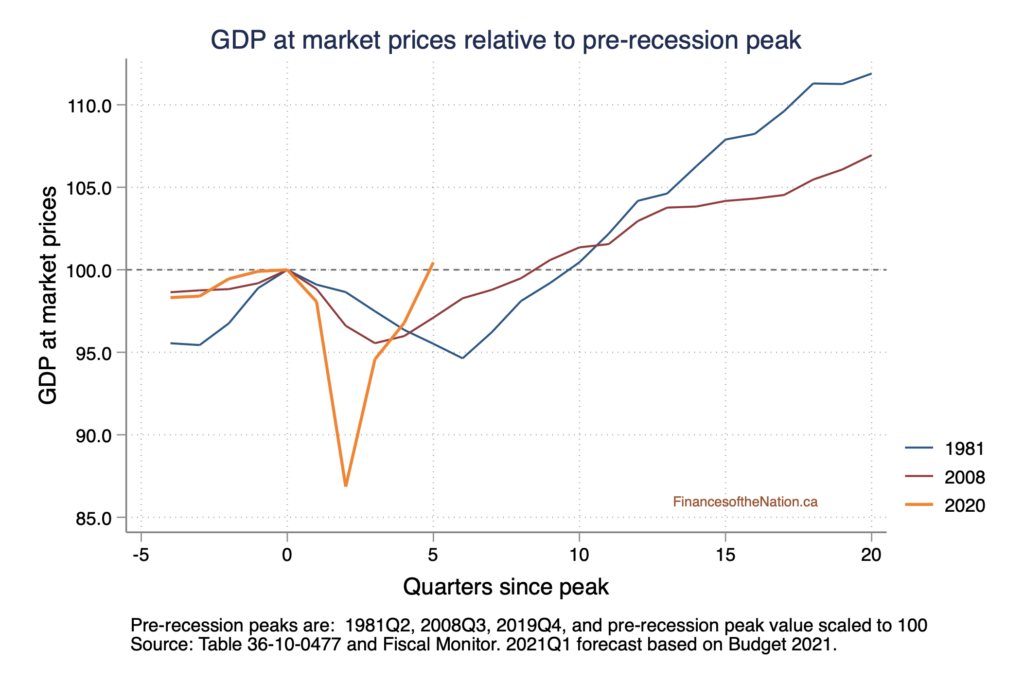

So, how is it going? To get a sense of the scale and speed of what has happened to the economy since COVID began, I have graphed certain key aggregates from the National Accounts for each quarter relative to the last peak in GDP at the end of 2019, and compared the path this time to past major recessions, in 1981 and 2008.

Figure 1 (which includes a forecast of first quarter 2021 GDP) shows GDP at market prices in real dollars. It is likely that GDP – which declined so sharply last spring — has already recovered to the levels seen at the peak before the pandemic. It’s been a V-shaped recession overall, with the recovery happening twice as fast as in the past major recessions of 2008 and 1982.

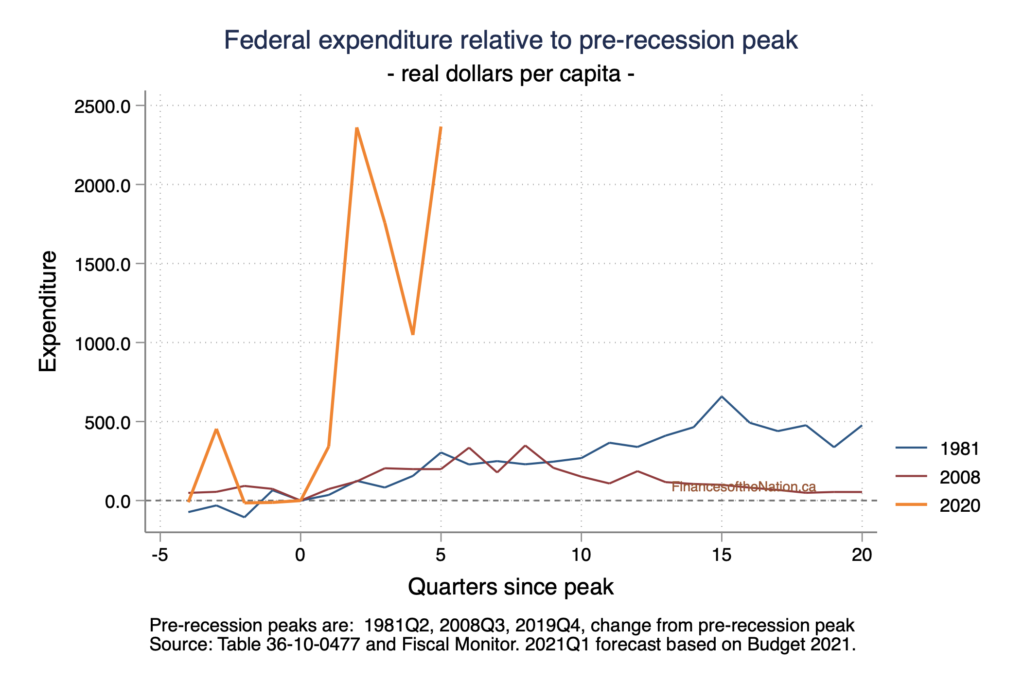

Figure 2 shows the patterns for federal government expenditure, which had doubled by the second quarter of 2020, and remained high through the end of the year. (When available, the data for early 2021 will show some decline, but spending levels still far above the levels of 2019.) The scale of Ottawa’s response to the crisis this time is remarkable compared to past recessions – or by virtually any standard.

We can’t really know if the quick recovery is due to Ottawa’s massive stimulus spending, or because of the improving public health situation. But the stimulus helped Canadians who needed it most, and it certainly reduced the risk of a prolonged, double-dip recession.

Have we spent too much? Perhaps.

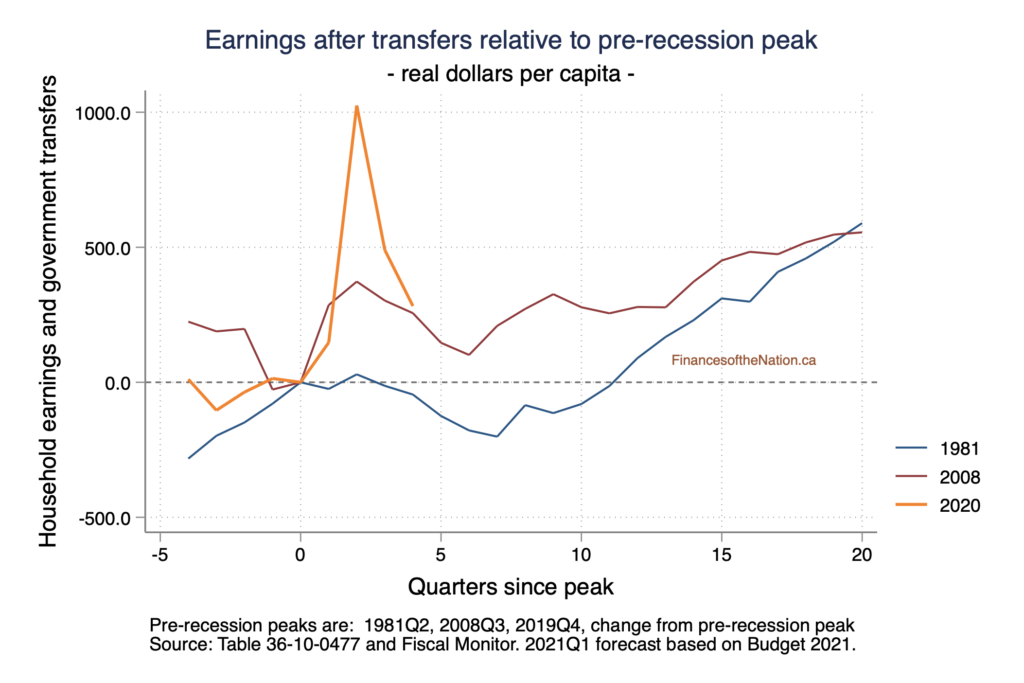

Figure 3 shows total employment and self-employment earnings plus government transfers to households. Notably, post-transfer earnings actually rose by second quarter 2020 to about 10 per cent more than before the crisis. For this reason, some commentators have complained that emergency benefits paid to displaced workers last spring exceeded their income losses by a wide margin.

But, with the end of CERB, post-transfer earnings have since declined again, and are now trending similarly to past recessions. And “overcompensation” need not be seen as a mistake, but as a conscious decision to increase transfers to Canadians with below-average income, at a time when they needed it most.

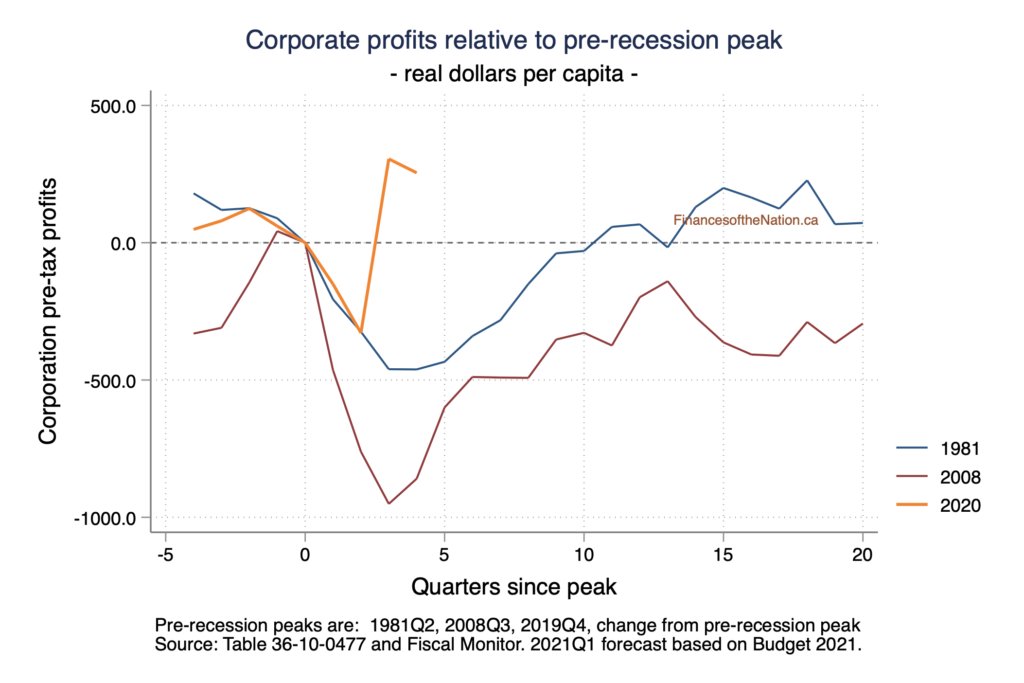

More troubling perhaps are the massive subsidies paid to businesses. Wage subsidies alone will cost Ottawa more than $100 billion by the end of the crisis. As depicted in Figure 4, corporate profits are now billions of dollars higher every month than they were in 2019, before the pandemic.

That is unprecedented in a recession. And raising incomes of corporate shareholders is hardly the best way to spend government funds.

But what about the debt?

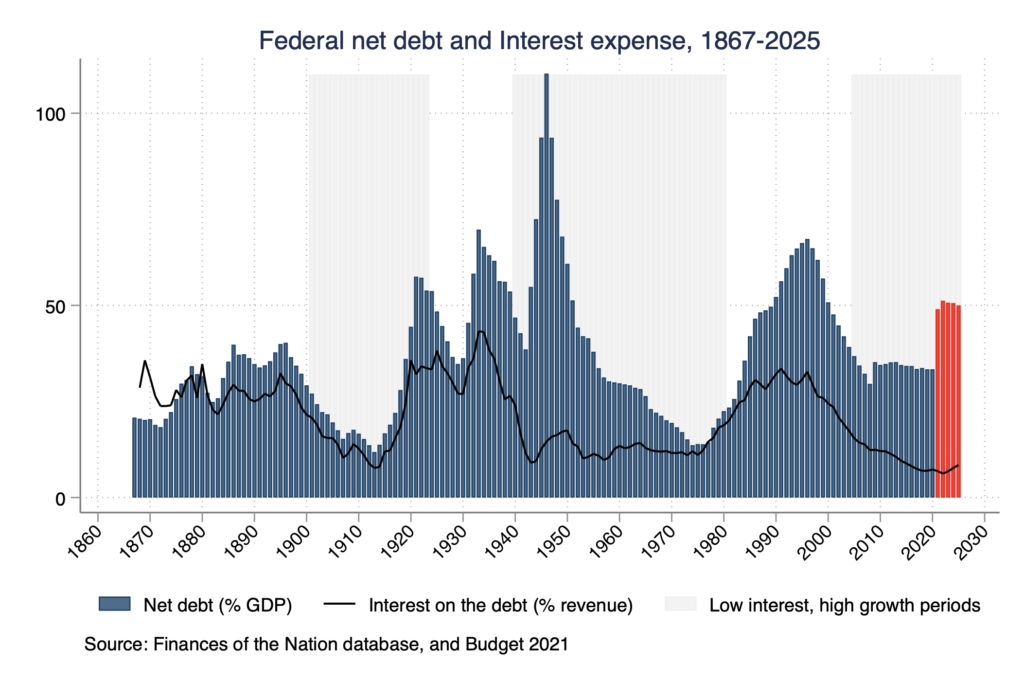

And so federal debt has risen sharply in the pandemic, reaching 51 per cent of our GDP compared to 31 per cent last year. That is the largest single-year change in our history, and a level not seen since the fiscal crisis of the 1990s.

To understand the rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio and what it could mean for the future, it is useful to look at the history of the federal debt. Figure 5 shows estimated federal net debt as a percentage of GDP from Confederation to today, together with a forecast for net debt to 2025 from Budget 2021. As shown in the figure, we are witnessing the largest single-year change in debt’s share of GDP in our history. Conservative commentators have taken note, and they are already calling for tax increases and spending cuts to pay down the debt.

But should they be? With long-term interest rates now below two per cent annually, the share of the federal budget that goes to servicing the debt has never been lower than it is right now. And that fact is leading to a fundamental rethink of our fiscal policy options.

What if we simply never pay back our COVID debt? As the debt matures in future, it could simply be rolled over with new bond issues. The new debt now being issued would still have costs, since the bonds would pay interest forever. But in the current low-rate environment, those costs are much smaller than before.

Dynamics of debt

Would such a policy be sustainable for Canada? Letting d = D/Y denote the debt-to-GDP ratio, we can show that debt must evolve over short time horizons according to the rule

∆d = (r – g) d + xwhere r is the interest rate on the debt, g is the growth rate of GDP, and x is the primary budget deficit as a percent of GDP. So the change in debt-to-GDP depends on the difference in interest and growth rates (r – g), and on how the government’s policy choices affect the primary deficit.

Long-term government bond yields are currently less than two per cent, so that r<g surely holds in the short run. If Ottawa returns to primary balance by 2025, then the debt-to-GDP ratio would therefore fall gradually as long as r<g in future.

In Figure 5, I have shaded in grey the periods where r<g by at least one percentage point. Canada experienced two such periods in the past, following the major depressions of the 1890s and the 1930s. It was during these periods that the federal debt – borrowed for the infrastructure boom of the turn of the last century and for the world wars – began to fall as a percentage of GDP. In short, when the debt has fallen in the past, it has been because r<g, and not through primary budget surpluses that retired the debt.

The one exception was the “debt crisis” of the 1980s and 1990s, when Ottawa ran surpluses – to the hardship of many Canadians – and succeeded in reducing the debt, despite high interest rates.

Many of the fiscal experts calling for fiscal consolidation today were senior officials in the Chretien and Martin governments that managed to “tackle the debt.” Their achievements then were impressive. But are they still fighting that last war, while disregarding the new fiscal reality facing Canada today?

If r<g holds up (and of course it might not), then debt should begin to fall gradually as a percentage of GDP, even if Ottawa continues to run small deficits in future. That’s why Ottawa’s recent budget promises major new spending without major tax increases in the coming years.

But there are caveats. Interest rates could rise again, or growth could founder. if that were to happen, then strict fiscal consolidation might be needed to keep our finances sustainable.

That means the risks of borrowing are borne by future taxpayers, and so the benefits of borrowing should mainly go to the future too.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland should take note. It makes most sense to borrow to finance investments in public infrastructure and human capital that will pay benefits into the future. But it makes little sense from an equity perspective to finance cash transfers to the elderly through borrowing, as Budget 2021 proposes to do.

The fiscal room gained from even the current low rates is relatively small. It cannot generate enough budget savings to finance large, permanent new spending programs without raising taxes.

Meanwhile, the pressures on our medicare system from the aging population will weigh ever more heavily on Canadian governments. The new larger federal debt could make that far more challenging to deal with.

The current low-interest environment is not a panacea for fiscal policy, and the resulting budget savings are small. It simply means that the current emergency measures are not leading to an unsustainable increase in the debt. That fact might help Canadians of all political stripes to sleep at night.

Note: This commentary is based on a speech to the CANCovid Network on May 6, 2021. Thanks to Susan Horton and staff at CANCovid for the opportunity to speak.