Frances Woolley

The fact that the phrase “immigrants have parents” even needs to be said reveals something about the framing of Canadian immigration policy: the tendency to see immigrants as production units, bits of human capital to slot into the Canadian economy and to fill Canadian skill shortages or to provide top talent.

Population aging means that tomorrow’s older Canadians can expect to enjoy a somewhat different standard of living from their counterparts today. Good policy can cushion this transition but no policy – not even increased immigration – can make demographic change go away.

There were 3.33 people between the ages of 25 and 64 for each person over 65 in Canada in 2020 — people to care for the frail elderly, keep the tax revenue flowing in to provide medical care and old age security payments, and support the robust stock and housing markets needed to maintain the value of older people’s assets.

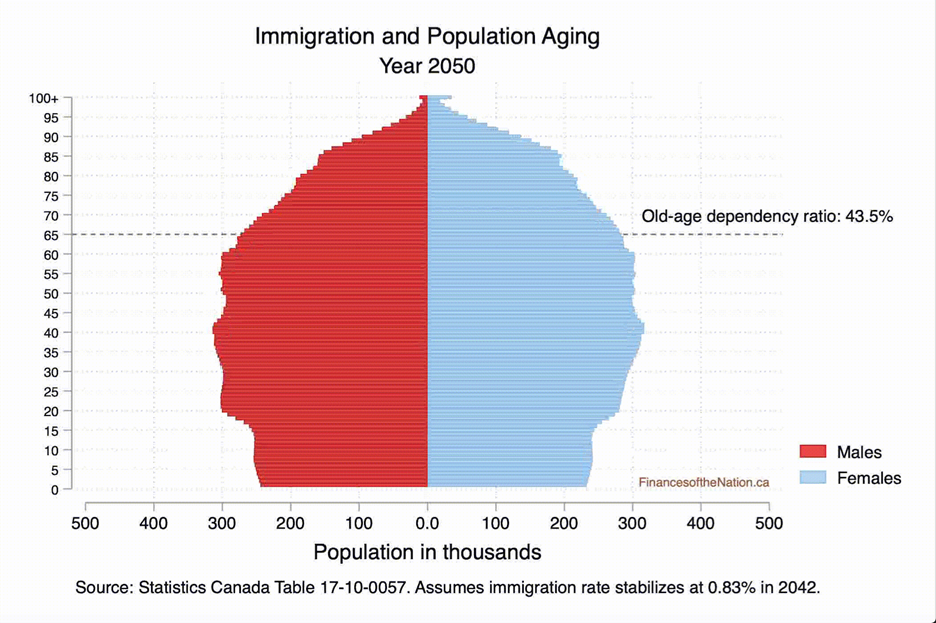

Fast forward 30 years and there will be only two 25-to-64 year olds for every person 65 and over, compared to the 3.33 today. The dependency ratio – the ratio of those over 65 to those 25 to 64 – is projected to rise from 30.9 per cent in 2020 to 43.5 per cent in 2050. The “oldest old” dependency ratio – the ratio of 85 and overs to people between the ages of 25 to 64 – will grow even faster, from four per cent now to 10 per cent by 2050.

It is widely agreed that these demographic changes will have negative fiscal and economic consequences — see, for example, reports by the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, the Department of Finance, other government departments and demographers. It is also widely agreed that certain policies, such as making more use of consumption taxes like the GST and HST, or raising the age at which people are eligible to claim old age security payments, would reduce the strain that population aging will put on government budgets. However, paying higher sales taxes or waiting longer to retire would require direct and tangible sacrifices from many Canadians — hence the perennial popularity of another supposed solution to population aging: increased immigration.

Immigration certainly mitigates the impacts of population aging, at least in the short term. Figure 2 (above) shows Canada’s population structure under the assumption that immigration remains at its current level in the short term and then stabilizes, trending towards 0.83 per cent of the population by 2042. Without these immigration inflows, the dependency ratio would be higher, and would increase more quickly.

On the basis of projections similar to the one shown in Figure 2, the CD Howe Institute has concluded, “changes in immigration levels have impacts on the margin only: no increase within the realm of practicality can prevent population aging.” Yet the CD Howe Institute, like other analysts, is insufficiently pessimistic about the impacts of immigration on population aging, because they ignore one simple fact: immigrants have parents too. Like older residents of Canada, parents of immigrants living abroad are at risk of needing care and economic support. Thus, we will argue, they can have a material impact on Canada’s “dependency ratio.”

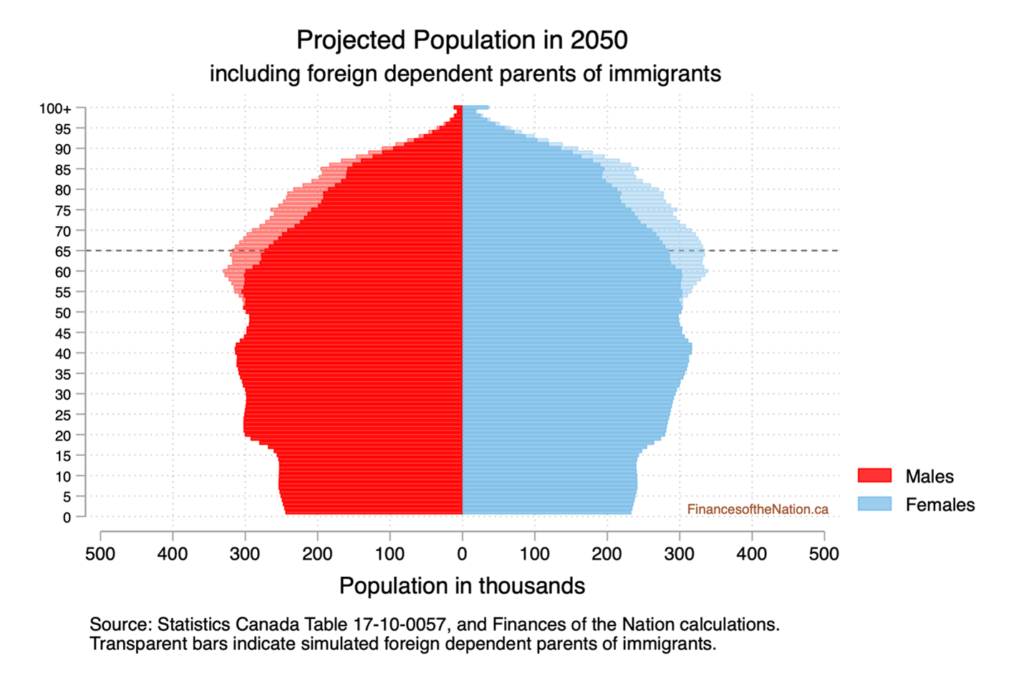

Figure 3 (above), constructed by the FON team, attempts to estimate just how big an impact the parents of immigrants could have on Canada’s population structure. A lot of guesswork went into creating Figure 3. We do not know which relatives Canadian immigrants support – it could be children, siblings, parents, grandparents or other relatives. Figure 3 focuses only on immigrants’ parents, not other relatives. The age of these parents is unknown, so we assumed the parents were on average 30 years older than their children. The life expectancy of these parents of immigrants is also unknown, so for simplicity the FON team used Canadian mortality projections for the foreign parents.

Another unknown is the degree of responsibility that immigrants have for their parents. A key factor influencing the amount of responsibility that children have for parents is the number of siblings they can share caregiving responsibilities with. The global average fertility rate is now around 2.3 children per woman. The fall in family size is most dramatic in China, the No. 2 source country for Canadian immigration in 2019. Chinese adults in their 20s and 30s today – the prime age for immigration – were born under China’s one-child policy. Most can expect to be the sole support of their parents in old age. While China’s case is the most dramatic, birthrates have plunged in India and other major source countries for immigrants in recent decades. Fewer siblings back home, together with increasing life expectancies, puts more pressure on immigrants to play an active role in caring for their aging parents.

Moreover, many immigrants now come from countries with strong traditions of filial support. In 2019 more than 40 per cent of Canada’s newcomers came from just three countries — India, China and the Philippines. In China and the Philippines, it is common for adult children to pay a “parent tax,” that is to provide their parents with financial support. For example, this recent study found 73 per cent of sons in China provided financial transfers to their parents, as did 83 per cent of daughters. In the Philippines, remittances were nine per cent of GDP in 2019. India has a weaker tradition of financial transfers from children to parents only because parents typically live with their adult children.

Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey is the best source of information on Canadians’ giving behavior. Focusing on landed immigrants in their peak earning years (35 to 54), my calculations show that while only five per cent of immigrants born in Europe make financial transfers to family outside Canada, that percentage rises to 13 per cent for those born in Asia, 20 per cent for those born in Latin America and 42 per cent for those born in Africa. These General Social Survey data, however, include substantial numbers of people who immigrated as children and may not have any close family outside Canada. If we were able to identify only those with parents outside Canada, the percentage making transfers would likely be higher.

Children support parents by providing time and care, as well as money. The parent and grand-parent super visa allows permanent residents of Canada to bring their parents into the country for up to two years at a time. In theory, parents in Canada temporarily on these super visas should be included in the Canadian population pyramids in Figures 1 and 2, but data on the number of visa holders currently in Canada is sparse, and we have no way of knowing how many grandparents-on-visas are factored into the current population projections.

Given the absence of hard data on responsibilities to dependants outside Canada, the FON team guess-timated. We associated each immigrant to Canada who arrived as an adult (age 21 or over) after 1972 with one-half of a dependent, non-resident parent. Taking these non-resident dependants into account makes a substantial difference to the 2050 dependency ratio, increasing it by approximately 30 per cent. If immigration levels were higher, the impact of these non-resident parents on Canada’s dependency ratio would be greater. If our assumptions have overstated the responsibilities that immigrants have to non-resident parents, the impact on the dependency ratio would be smaller.

Canada’s benefit system for seniors is at least in part a pay-as-you-go scheme: health care, public contributions to long-term care, old age security and the guaranteed income supplement are all funded out of current tax revenues. Even the components of the retirement system that are backed by assets and investment funds, like private savings and the Canada Pension Plan, are viable only if there are people willing to buy assets when retirees want to sell them, and enough economic growth to create a buoyant stock and real estate market. With a pay-as-you-go retirement benefit system – like any kind of Ponzi scheme or multi-level marketing arrangement – the greater the number of young people paying into the plan, the greater the benefits available to current retirees. Hence, the temptation to persuade immigrants to join the Canadian retirement benefit system is real.

However many immigrants to Canada have already been co-opted into a different kind of Ponzi scheme: an arrangement whereby parents save for retirement by investing in their children, in the expectation that the children will return the favour by supporting them in their old age. This “parent tax” is a kind of pay-as-you-go pension plan that has worked for generations.

There is nothing wrong with children supporting their parents in retirement, just as there is nothing wrong with a taxpayer-funded retirement system. However if immigrants are expected to contribute to both the taxpayer-funded system and the familial support system, they are likely to be overstretched and unhappy. If there are enough newcomers to make a material difference to Canada’s dependency ratio, there will be enough newcomers to make a material difference in Canada’s election outcomes, and the amount of support for the public system.

That fact that the phrase “immigrants have parents” needs to be said reveals something about the framing of Canadian immigration policy: the tendency to see immigrants as production units, bits of human capital to slot into the Canadian economy and to fill Canadian skill shortages or to provide top talent. If instead we see immigrants as people, we understand that immigrants come with networks of connection and responsibility. They come with values and beliefs and ideas of what it means to live a good life – and these will influence the types of choices that immigrants make and the public policies they will support.

Some generations are luckier than others – some live through multiple wars, others experience years of peace. Some enter the job market during boom times, others during a recession. Some generations experience poverty in old age, others are protected by government benefits. This generational luck is a product of world events, and big demographic and economic trends. Public policy can moderate the impact of this generational luck, but it cannot make demographic trends go away, or completely cushion people from their impacts.