Ayaka Behro and Trevor Tombe

The Conservative Party of Canada proposes to increase the growth rate of the Canada Health Transfer to at least six per cent per year for a decade. We explore the implications of this for overall health transfers and for provincial governments.

Canada’s federal government provides significant transfers to provincial governments to (nominally) support their health-care systems. This year, total funding through the Canada Health Transfer exceeds $43.1 billion, making it the largest federal-provincial transfer in Canada by a wide margin.

To evaluate the Conservative proposal to increase its growth rate to at least six per cent per year, one must appreciate both the importance of this program for provinces and how recent reforms affected its growth.

Using Finances of the Nation’s major transfers database, we can illustrate the importance of CHT in Canada. The Tableau storyboard below illustrates several important statistics.

The key recent change to the CHT evident in the last panel above is equalizing the per-capita values of the transfers. This was a significant reform to federal transfers — first introduced in the 2007 federal budget under Prime Minister Harper, though fully implemented for CHT by 2014/15. Today, all provinces receive exactly the same amount person while previously some higher-income provinces (notably Alberta) received less — for reasons we don’t need to get into now.

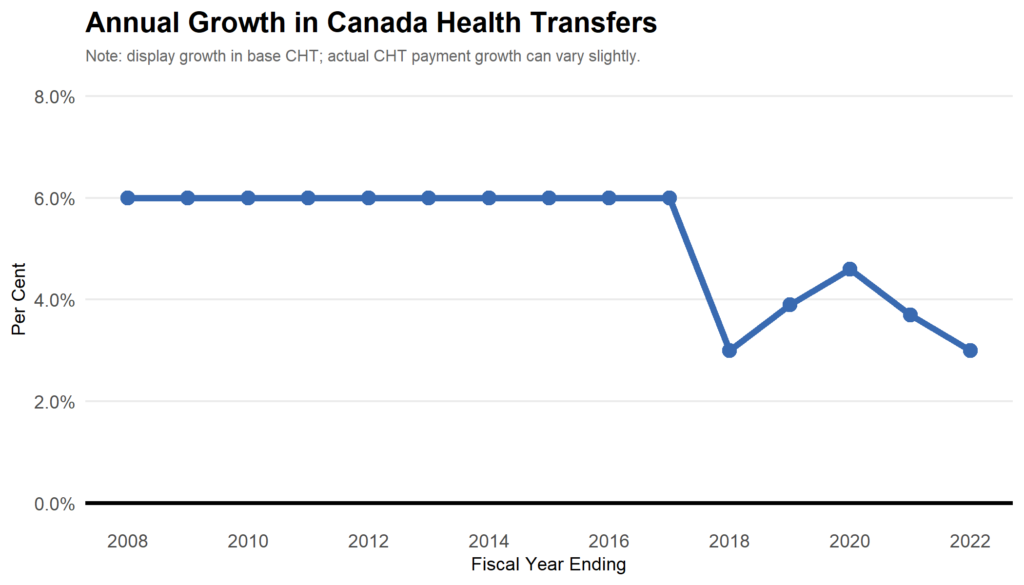

Also evident in the above panels is the substantial growth in the total value of the CHT. From slightly more than $20 billion to all provincial governments in 2007 to more than $40 billion by 2020, the CHT has been a key source of financing to provinces in recent years. Starting with the “10-Year Plan to Strengthen Healthcare” agreed to between the federal and provincial governments in 2004, base CHT grew at a rate of six per cent per year from 2005/06 to 2013/14. But in 2012, the Harper government introduced a new growth formula where CHT grows with Canada’s overall economy. It kept the six per cent growth rate for an additional three years to 2016/17, but after that growth in CHT was tied to a three-year moving average of nominal GDP growth with a minimum growth rate of three per cent.

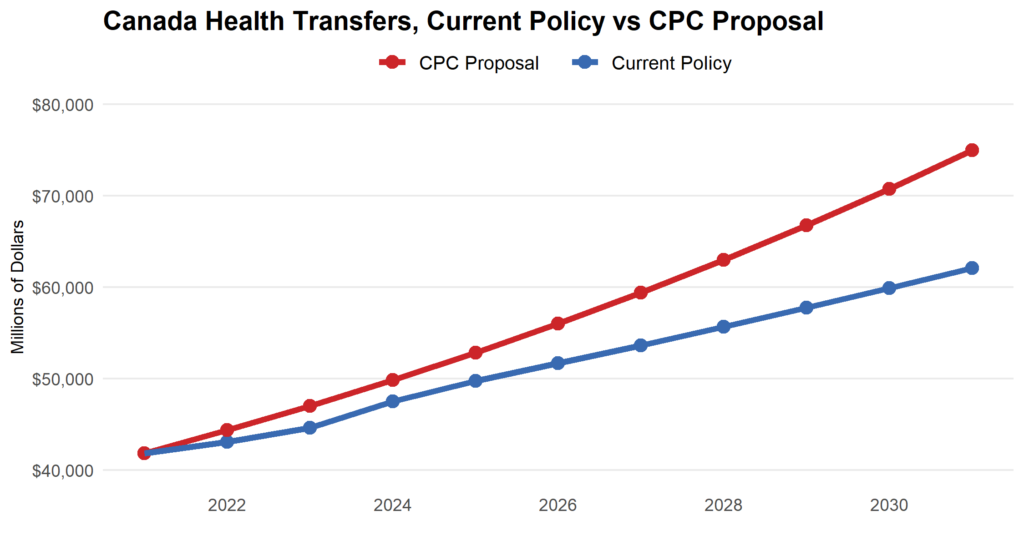

The proposal to increase CHT growth to six per cent annually would represent a significant increase. Even small differences in growth rates can lead to significant increases when sustained over time. By 2025/26, for example, a six per cent growth rate would increase the total value of CHT to provincial and territorial governments by more than $4.3 billion — or 8.4 per cent. By 2030/31, it would result in nearly $13 billion in additional payments that year — or a nearly 21 per cent increase above current policy. We illustrate this below and can confirm as correct the party’s estimate of this resulting in nearly $60 billion additional dollars in health transfers to provinces over the next decade.

On average, over the next decade, this represents a roughly two percentage point increase in the annual growth rate of the CHT.

Implications for Provincial Governments

Provincial health systems are already strained by COVID, but will also see mounting pressures for years to come because of a large but slower moving source: aging populations. This matters for provincial budgets for the simple reason that health spending rises dramatically with age. Using data from the Canadian Institute of Health Information, we display below the provincial variation in health expenditures and differences in spending across age groups. Per-capita health spending for individuals aged 65-plus is significantly higher than health spending on younger individuals.

Over the next decade, total spending on provincial health care may rise (according to recent estimates) by more than 60 per cent. But current health transfers are set to increase by less than 50 per cent. If CHT growth increases to six per cent per year, however, then within a decade the total CHT would increase by nearly 80 per cent — potentially increasing CHT from 23 per cent of provincial health spending today to 27 per cent in 10 years.

This matters for more than just health financing. Provincial finances overall are on an unsustainable path. Boosting the growth in CHT from an average of roughly four per cent per year now to six per cent per year could help modestly improve provincial finances — and the federal government has room to do so. To illustrate this, below we show the Finances of the Nation debt sustainability simulator results with higher rates of CHT growth.

The increase seems to point to aggregate provincial net debt of 50 per cent of GDP by 2031, rather than the 54 per cent in the Finances of the Nation baseline projection. While this does come at the cost of rising federal debt levels, that is the level of government which has additional fiscal room to spare. While there are certainly pros and cons to consider when changing federal transfer programs, increasing health transfers specifically is quite likely going to be an important policy tool to ensure long-run sustainability of provincial governments.