Mikal Skuterud and Tammy Schirle

We tend to give other voters the advice to ask themselves the following of any proposal: What problem do we want policy to address and can this policy succeed? In our view, a key policy challenge is reducing long-term joblessness.

The economic recovery remains strong, as gross domestic product and household consumption appear now to be approaching pre-pandemic levels. But the job market remains sluggish, raising concerns the pandemic could have longer-term scarring effects.

What would it take to get Canada back to normal?

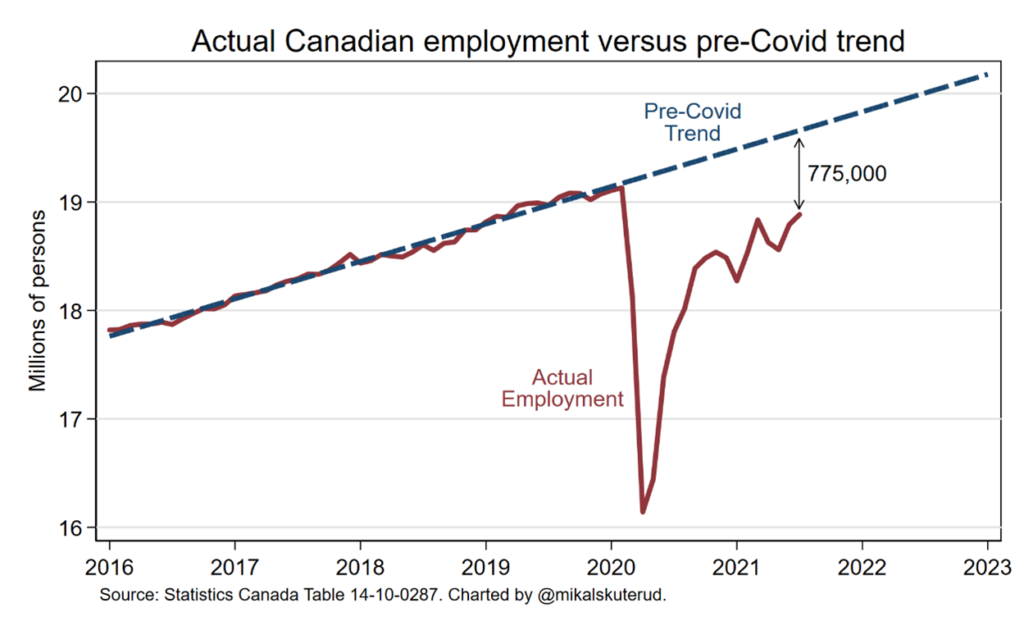

As of July 2021, 250,000 of the three million jobs lost in the first two months of the pandemic had not yet returned. But this figure ignores gains that otherwise would have been made in the past year. Using a linear trend to predict normal growth suggests the current jobs shortfall is three times higher (see chart below), although that reflects in part the fact that pandemic travel restrictions choked off new immigration. A more reasonable target is to get back to the February 2020 employment rate of 61.8 per cent, which requires 500,000 more jobs.

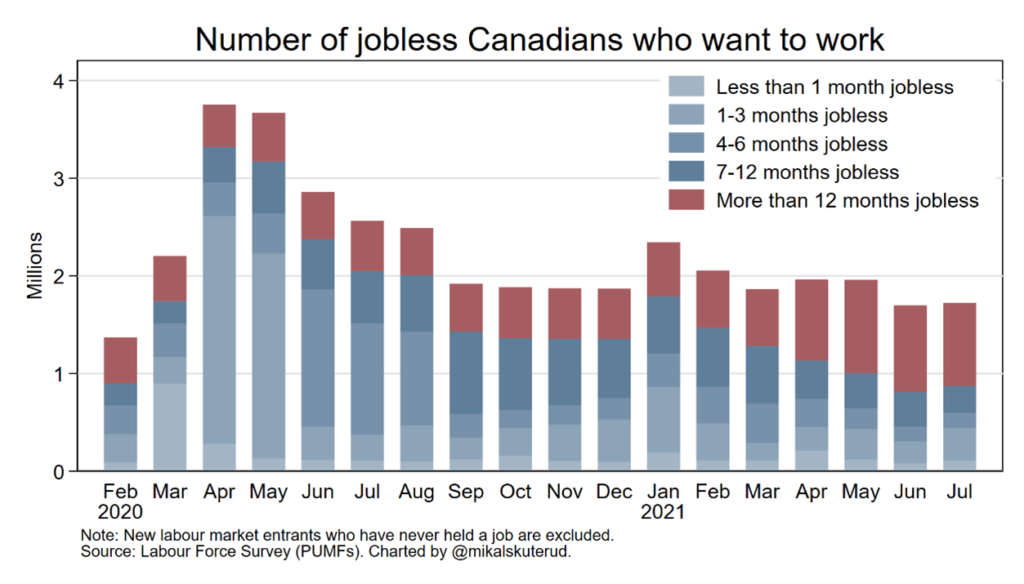

The challenge, however, is bigger than finding jobs for 500,000 people. As of July 2021, there were 1.7 million Canadians with past employment experience who said they wanted a job but did not have one (350,000 more than in February 2020). Of greater importance is that a larger-than-usual share of these people have been jobless for a long time: one half had been jobless for more than one year, and two-thirds had been jobless for more than six months. Evidence tells us that the longer workers are jobless, the less likely they are to return to work. When they do return, the long-term jobless tend to experience significant earnings shortfalls. Given the substantial social costs of long-term labour market disengagement, which can become permanent, getting the long-term jobless back to work should be a policy priority in the coming months.

What is the case for hiring subsidies?

The key obstacles preventing employers from boosting employment to optimal long-run levels are known as adjustment costs. Of particular significance are one-time costs associated with hiring, such as advertising, interviewing and training. Under the right conditions, a reduction in these costs via subsidies can result in an increase in the number of workers that a firm wants to hire, thereby boosting employment levels. Moreover, when employers find it challenging to find workers, any wage subsidies have the potential to end up in workers’ wallets in the form of sign-on bonuses or higher wage rates.

The evidence also suggests such wage subsidies can work. Meta analyses of real-world active labour market programs tell us there is significant potential for private-sector wage subsidies to generate employment gains, especially when introduced during recessions. The evidence also points to greater beneficial impacts for women and those experiencing long-term unemployment.

With this in mind, subsidies are an attractive option right now, especially hiring subsidies that target employers who recruit applicants from among the long-term jobless. This was the approach recommended by Lange and Skuterud in their recent Policy Options article, suggesting that subsidy eligibility be restricted to employers who hire the long-term jobless.

In March 2020, the federal government introduced the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) program to support employers experiencing revenue declines due to the pandemic. The parameters and rules have evolved over time, and the current program is expected to end Oct. 23. Generally speaking, to become eligible, a business must demonstrate a drop in revenues, and then experience a continuing revenue drop of more than 10 per cent to continue receiving the subsidy. The subsidy can be used to cover wage costs of active and furloughed employees, and the subsidy rate depends on revenue drop experienced by the business.

So what’s being proposed by parties now?

The Liberal Party, the Conservative Party of Canada and the New Democratic Party have all proposed hiring subsidies in their parties’ platforms. But each proposal has its potential strengths and weaknesses.

First, the Liberal Party plans to extend the Canada Recovery Hiring Program (CRHP). This had been scheduled to end on Nov. 20, but the Liberals propose extending it to March 2022. Eligibility criteria for CRHP is mostly the same as for CEWS — requiring a revenue drop to qualify, and noting that businesses can apply only to either CRHP or CEWS within a given period. The nature of the subsidy is quite different from CEWS, in that the CRHP covers incremental labour costs. The subsidy rate is currently 50 per cent, but falls to 20 per cent by November.

The structure of the program offers a subsidy when payroll costs for active employees are higher than in a base period (March 14-April 10, 2021), which can help businesses cover the adjustments costs that would otherwise limit employment gains. The reduction in the subsidy rate over the coming months also encourages employers to move quickly, and avoid delay in returning to their anticipated long-run employment levels. The subsidy also covers increases in paid hours worked among existing employees. Employers who retained their employees through the pandemic, and don’t see an increase in payroll costs among active employees, would not benefit from transitioning away from CEWS to CRHP.

Unfortunately, data regarding uptake have yet to be released. The program focuses on employers experiencing persistent revenue losses. Arguably, those businesses that had laid off employees at the beginning of the pandemic but had not recalled employees before April 2021 may never be able to rehire those workers. With ongoing uncertainty in many sectors – especially food services and tourism – many of the eligible businesses may be reluctant to ramp up payrolls. While the program is estimated to cost $595 million, these factors may result in much lower costs than originally anticipated.

Second, the Conservative Party’s proposed Job Surge Program (JSP) would begin when CEWS ends and would offer a subsidy to help cover the payroll costs of all net new hires. The minimum subsidy rate is 25 per cent, while a maximum rate of 50 per cent would be offered if new hires are recruited from the pool of long-term unemployed. All businesses would be eligible to apply, including those expanding beyond pre-pandemic levels, and the program would last six months.

The generous wage subsidies should be expected to spur employment growth. In light of anticipated structural changes in labour demand post-pandemic, one advantage to offering the subsidy to all businesses (rather than just those experiencing a drop in revenues), is that the subsidy would also encourage employment growth in industries able to adapt. This could encourage sectoral reallocation of workers, speeding up the recovery. Moreover, targeting long-term jobless Canadians is appealing.

While restricting eligibility to net new hires ensures employers are not incentivized to simply replace existing employees, the JSP could adversely affect employee retention if employers restrict hiring to six-month contracts. While focusing on new hires has advantages, the subsidy would not cover the wage costs associated with increasing hours among existing employees, potentially leaving some workers with pandemic-level reduced hours.

Overall, one may expect the JSP to be a more costly program than the CHRP. One reason is that employment expansion associated with sectoral reallocation may occur in sectors where wages and salaries are higher (for example in jobs with relatively high digital skills), implying a higher subsidy cost. The main reason, however, is the eligibility of all businesses for a JSP subsidy.

Third, the NDP are committing to extensions of wage and rent subsidies for small businesses until they are able to fully reopen. It is not clear how one would address the unfortunate problem that some businesses may never be able to reopen, implying subsidies in perpetuity. To get people back to work, the party proposes long-term hiring bonuses to cover the employer portion of EI and CPP premiums for new or recalled employees. While the NDP proposes creating more than one million new jobs in its first mandate (an entirely reasonable objective in our opinion, even in the absence of subsidies), its proposal leaves many details unspecified at the time of writing.

Which party has the best proposal?

There are merits to each of the party’s proposals outlined here, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. We are inclined to believe the Conservative Party’s JSP proposal would create the most jobs in the short term, but that would come at a bigger cost.

We tend to give other voters the advice to ask themselves the following of any proposal: What problem do we want policy to address and can this policy succeed? In our view, a key policy challenge is reducing long-term joblessness. Our concerns reflect the increasing difficulty that individuals have in finding work the longer they are away from jobs; the personal costs to those individuals; as well as future costs associated with supporting them with the available income support programs (provincially and federally). With the long-term jobless in mind, the proposed JSP appears superior. We recommend voters, and each of the parties, consider how various proposals might better target the long-term jobless.