Michael Smart

The rise of small-business incorporation is suppressing the taxable incomes of rich Canadians. The growing gulf between top personal tax rates and the low rates paid by small CCPCs is driving the rise of incorporation.

There has been much concern in the past decade about the rise in top incomes, and whether the rich are paying their fair share of taxes. So, many observers might be surprised to learn that the rich are in fact not getting richer in Canada – at least, not according to the official statistics. But, as I argue in a recent research paper, that is likely due to tax avoidance through small-business corporations, and it is a sign of a larger problem in our tax system.

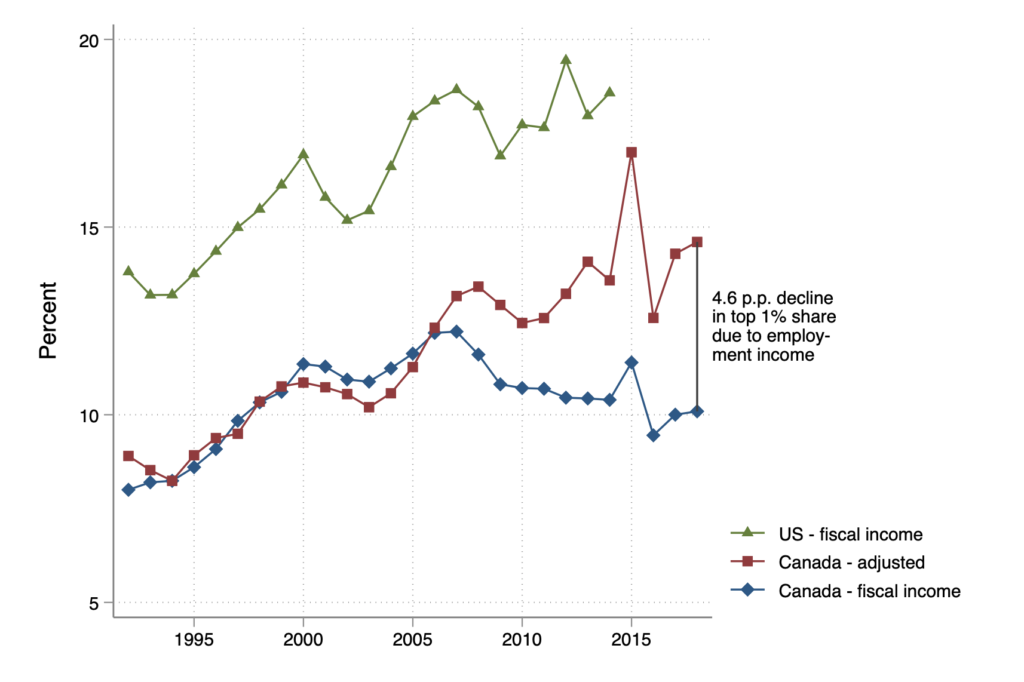

Statistics Canada reports that the top one per cent of Canadians earned 10.0 per cent of total incomes in 2018, about the same as their 10.2 per cent share in 1998. That’s a far cry from trends in the United States, where the top one per cent’s share has risen to 19 from 16 per cent of total U.S. incomes over the same time period.

Could the experience of the rich Canadians really be so different than our southern neighbours – and could those who see rising inequality as a growing problem really be so wrong?

Official statistics are based on the incomes Canadians report on their personal income tax returns. But many of the top one per cent are high-earning professionals such as doctors and lawyers who can establish small-business corporations and declare their earnings as business income rather than personal income. So the personal incomes of high-income professionals are artificially depressed, a sign of a growing problem with tax avoidance by high-income Canadians.

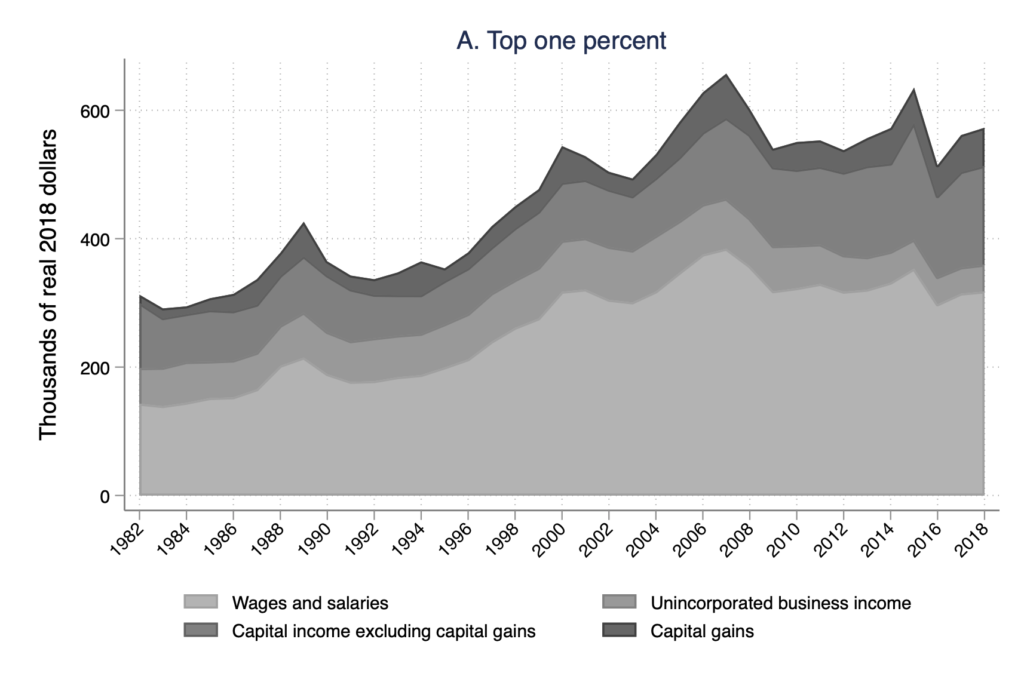

Figure 1. Composition of top incomes, 1982-2018

Figure 1 shows the composition of the incomes of the top one per cent and 0.1 per cent of taxpayers since 1982 in real dollars per taxpayer, from the administrative personal tax microdata. Both wages and self-employment (unincorporated business) income have declined in real terms since their peak in the early 2000s. The effect is especially pronounced for the top 0.1 per cent, for whom taxable employment (including self-employment) earnings have declined by 36 per cent since their peak in 2007.

What the charts don’t show is why this is happening — the increasing move to incorporation by professionals, which is distorting this picture.

Small-business incorporations by professionals were uncommon in the past but that has changed over the past two decades. There were 2.6 million Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs) in 2018 — a substantial increase over the 1.5 million that existed in 2002. Based on Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, 46 per cent of self-employed Canadians were incorporated in 2018 (including 32 per cent of self-employed businesses with no paid employees), compared to 36 per cent in 2002. The increase in incorporation has been particularly high in the service sectors, including health care, professional services, construction, and accommodation and food services.

Average unincorporated business income (UIBI) for the top one per cent has declined by more than 50 per cent in real terms from its peak in 2004 to 2018. This reflects a sharp decline in the fraction of the top one per cent of taxpayers reporting any income in this category, as small business owners turn increasingly to incorporation.

Is small business a tax shelter?

For years, federal and provincial governments have been slashing corporate tax rates especially on small businesses, even as they raise the top tax rates on personal income. So, the incentives to incorporate, then hold their money in a corporation, are stronger than ever.

Small corporations[1] now face a statutory tax rate on earnings that averages about 12 per cent across all provinces – less than one-half the 26 per cent tax rate for larger companies and far, far less than the top personal tax rate of 53 per cent. So, the incentive to convert personal income to corporate income to avoid taxes is stronger than ever.

In principle, business owners will eventually pay more tax on their earnings when they pay out the business income as salary or dividends. But there is a real concern that rich Canadians can find ways to use the money in their corporations without ever paying tax on it. Tax avoidance strategies for business owners include:

- Income sprinkling, or income-splitting as it is often called, is a strategy that can be used by high-income owner-managers of small private corporations to divert some of their income to family members with lower personal tax rates.

- “Surplus stripping” transactions which convert company dividends into capital gains. Capital gains are taxed much more lightly than dividends in Canada. In some cases, no tax is paid at all because of the lifetime capital gains exemption of approximately $900,000 on the disposition of qualified small business shares.

- The recently approved Bill C-208 makes surplus stripping easier than ever before. It allows those business owners to claim proceeds from the sale of shares to an adult child or grandchild as capital gains, rather than as dividend payments. That could include “paper transactions” in which the owner’s descendants do not even carry on the business themselves. The federal Finance Department has announced its intention to enact new legislation in the fall that would limit tax avoidance under Bill C-208. But the announcement also opened the door to permanently lowering taxes on intergenerational transfers of businesses. And, until the new legislation is released, the government will leave the C-208 loophole wide open for businesses to exploit.

- Canadians are supposed to pay tax on their accumulated capital gains at the time of death, a tax rule known as “deemed realization”. But it appears common for high-wealth CCPC owners to engage in estate freeze transactions that permit the transfer of shares in the business to family members without tax during the owner’s lifetime, deferring indefinitely capital gains taxes that would otherwise be payable at death.

The federal Finance department is aware of tax avoidance through CCPCs and has taken steps to limit it. In 2018, the federal government enacted certain changes to the rules affecting these small corporations. Notably, the tax on split income was expanded to apply to more types of payments to family members, including dividends paid to adult family members, except where the shareholder was “actively engaged” in the business. Additionally, the new rules reduced the small business deduction for corporations with more than $50,000 in annual passive investment income, and implemented other changes to reduce tax-preferred saving through corporations. Finally, the government had proposed new rules to limit surplus stripping from corporations but, after strenuous objections from tax professionals and industry groups, these proposals were ultimately withdrawn.

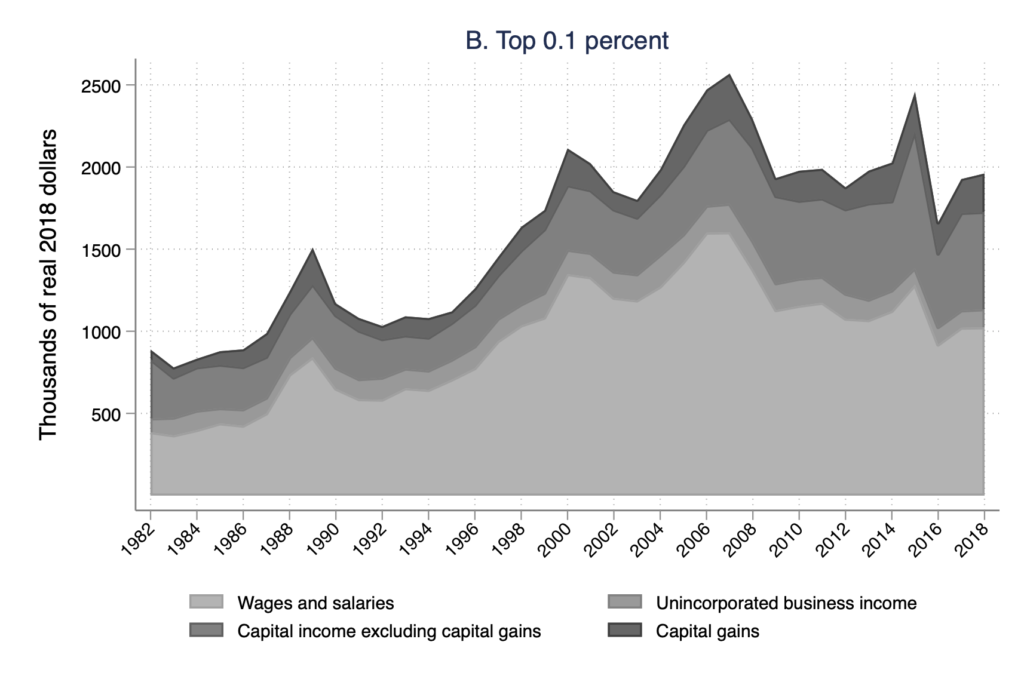

Figure 2. Effect of corporate taxes on unincorporated business income, 1994-2014

Note: Each point in Figure 2 plots the change in real log UIBI of the top one per cent of taxpayers in a province since five years earlier against the corresponding change in the corporate tax rate. Diameters of circles are proportional to provincial population. The slope of the line of best fit is 3.25 (se = 1.11). This suggests that an eight-percentage point decline in the corporate tax rate (the average decline since the year 2000) causes a 26 per cent decline in unincorporated business income in a province.

When high-income individuals incorporate, the salary and self-employment income they report on their personal tax returns falls, and the top one per cent’s share of total national income in the official statistics falls with it. To show how falling small business tax rates are driving this trend, my research looked at data on the self-employment incomes of the top one per cent of taxpayers in each province since 1994, and examined the relationship between the fall in self-employment incomes and provincial tax cuts.

Figure 2 shows a clear negative relationship between tax rates and unincorporated business income: When a province reduces its small business corporate tax rate, more high-income Canadians turn to incorporation, and reduce their reported personal incomes.

That’s an indication that the rise of incorporation is driven by the desire to avoid personal taxes – which is bad for the efficiency of our tax system, and for the revenue governments raise by taxing high-income individuals.

Incorporation and income inequality

My research therefore suggests that a substantial portion of the rise in incorporation and the decline in unincorporated business income in the past 20 years is motivated by desire among the top one per cent to shield incomes from personal taxation.

Incorporation also distorts the true picture of their overall income and of top-tail income inequality in Canada. The rich probably are getting richer in Canada – though official statistics based on personal tax returns don’t show it. These developments stand in stark contrast to the United States, where high-income individuals are declaring more business income as personal income. As argued by Kopczuk and Zwick (2020), reforms in the U.S. since 1986 have given tax advantages to income earned through S-corporations and other structures whose income flows through to individual owners, rather than traditional C-corporations that are subject to separate entity-level taxes, like corporations in Canada are.

To show the importance of the shift to incorporation in Canada, I performed a simulation. I calculated how high the top one per cent’s share of total income would be today if the share of employment and self-employment income on their tax returns had remained fixed at its 1994 level, instead of declining as it did in reality due to the rise of incorporation.

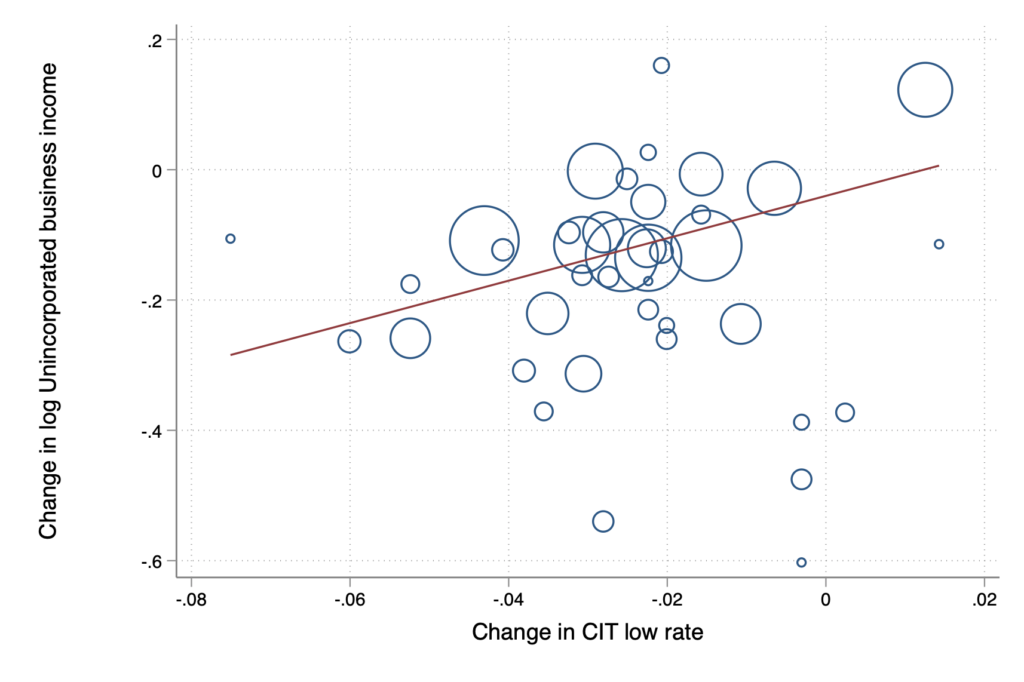

Figure 3. Effect of income composition on top one per cent shares

Figure 3 shows the resulting adjusted income share of the top one per cent in Canada, compared to the share in the official statistics, and compared to the corresponding share in the United States.[2] The top share would have been 14.6 per cent in 2018, if the employment incomes of the top one per cent had grown at the same rate as other components of income, or 4.6 percentage points higher than observed in the unadjusted fiscal income data. The top share of adjusted income remains five to six percentage points below the top share of fiscal incomes in the United States in all years, but the evolution of the U.S. and adjusted Canadian series are very similar.

Even after adjusting for the rise of incorporation through the simulation, top income inequality remains greater in the U.S. than Canada – the rich truly are richer south of the border. But the diverging trends over the past 15 years seem to be explained well by the increasing attractive business tax climate in Canada.

The facts presented here suggest that the rise of incorporation is suppressing taxable incomes of rich Canadians in recent years – and that the growing gulf between top personal tax rates and the low rates paid by small CCPCs is driving the rise of incorporation.

Not all small businesses are tax shelters by any means. Indeed, most small business owners probably will pay a high effective tax rate on their earnings eventually, once business income is paid out to owners in the form of dividends and salary. But the opportunities available to some business owners through income sprinkling, surplus stripping, and other tax planning strategies are a real challenge to the fairness and efficiency of our business tax system. The newly enacted Bill C-208 makes that situation worse, facilitating surplus stripping through paper transactions among family members.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

[1] CCPCs with assets less than $15 million are eligible for the Small Business Deduction, which reduces their corporate tax rates on active business incomes up to $500,000 annually. The threshold is up from $200,000 in 2000, or about 70 percent in real terms.

[2] The US data are taken from Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman (2018), “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States.”