David Andolfatto

Canada’s federal deficit is currently forecasted to be $343 billion in fiscal year 2020-21, or more than 15% of gross domestic product (GDP). Not surprisingly, this deficit and the associated accumulation of debt is attributable to the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal budget deficits are, however, expected to continue well beyond 2020. This commentary discusses how we should think about the federal government’s debt, and what perspective we should take that may be different from how we are used to thinking about other kinds of debt.

Introduction

This year, Canada’s government is forecasting a historically large budget deficit, primarily due to the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some analysts have expressed concern over the prospect of budget deficits extending beyond the pandemic. What is likely to happen if fiscal policy continues on this path? Are there any limits to how large the debt can grow? Will inflation and interest rates start to rise? Will the exchange rate depreciate? Might the government ever be in danger of defaulting? Will austerity measures need to be implemented? And if the debt is not paid back, will we in effect be passing the burden of repayment on to our children?

These are all very good questions, none of which I’m going to answer. Not directly, at least. Instead, I want to talk about how we should think about the federal debt—what perspective we should take that may be distinct from the way we are accustomed to thinking about debt in general. I then want to see where this perspective leads us in terms of determining possible answers to the questions posed above.

As various economists have pointed out over the years, the federal government debt is not exactly like “debt” in the way the term is commonly understood.[1] Most of us have a view of debt that’s very personal. When we incur a debt, we expect to have to pay it back at some point, even if it means having to work harder or cut back on our spending. Passing our personal debt on to our children is something most of us wouldn’t entertain, even if the practice was legal. If the federal debt was like personal debt, it would be easy to explain. But this “government as a household” analogy is imperfect, at best. The analogy breaks down for at least four reasons.

First, a household, unlike a government, has a finite lifespan. So while a household must eventually retire its debt, a government can, in principle, refinance (roll over) its debt indefinitely. Yes, debt has to be repaid when it comes due. But maturing debt can be replaced with newly issued debt. Rolling over the debt in this manner means that it need never be “paid back.” Indeed, it may even grow over time in line with the scale of the economy’s operations as measured by, say, population or GDP.

Second, unlike personal debt, the federal debt consists mainly of marketable securities issued by the Government of Canada (GoC). In fact, prior to the establishment of the Bank of Canada (BoC) in 1935, GoC securities labelled “Dominion notes” formed an important part of the money supply.[2] Today, GoC securities exist primarily as electronic ledger entries. According to Bulusu and Gungor (2018), about $500 billion of short-term debt contracts called repos are traded each month using GoC securities as collateral. Most of these transactions are evidently driven by the need for cash.[3] Because investors value the liquidity of GoC securities, they trade at a premium relative to other securities. In other words, investors are willing to carry GoC securities at relatively low yields, the same way we are willing to carry insured bank deposits at very low interest rates.

Third, the federal government has ultimate control over the nation’s legal tender. Since the federal debt consists of GoC securities promising payment in the legal tender, a technical default can occur only if the government permits it. The situation here is similar to that of a corporation financing itself with debt convertible to equity at the issuer’s discretion. Involuntary default is essentially impossible.[4] This aspect of GoC securities renders them highly desirable for investors seeking safety, a property that again serves to drive down their yields relative to other securities.

Fourth, since most of the federal debt is held domestically, it constitutes domestic private sector wealth. The extent to which it constitutes net wealth can be debated, but there’s not much doubt that at least some of it is viewed in this manner.[5] The implication of this is that increasing the national debt makes individuals feel wealthier. When this “wealth effect” is generated by deficit-financed tax cuts (or transfers) in a depression, it can help stimulate private spending, making everyone better off. When the economy is at or near full employment, however, such a policy is instead more likely to increase the price level, generating a redistribution of wealth.

Together, these considerations suggest that we should consider viewing the federal debt from a different perspective. In particular, it seems more accurate to see federal debt less as a form of debt and more as a form of quasi-money in circulation. Investors value the securities making up the federal debt in the same way that we value money—as a medium of exchange and a safe store of wealth. The idea of having to pay back money already in circulation makes little sense in this context. Of course, not having to worry about paying back the federal debt does not mean there is nothing to be concerned about. But if federal debt is a form of money, wherein lies the concern?

Debt service

Unlike the Dominion notes issued in the past, GoC securities bear interest (or sell at discount, in the case of bills). So even if the national debt doesn’t have to be paid back, it still needs to be serviced. The interest expense associated with carrying debt is called the “carry cost.”

Debt management strategies employed in government treasury departments seem heavily influenced by corporate practices. But corporations have to worry about rollover risk, whereas governments can generally rely on their central banks to support refinance operations in a crisis. As well, corporations operate on behalf of a narrower set of interests than a federal government. Given these considerations, it is not immediately clear whether corporate debt management principles apply to the Department of Finance.

If one had to draw on the corporate sector for analogy, an example one could appeal to is that of a bank. A significant amount of debt issued by banks is in the form of insured deposit liabilities. Because insured deposits are safe and because they constitute money, investors are willing to carry deposits at low yields. As a result, deposits are a very cheap source of funding for banks. This low-cost source of funds is used to carry higher-return assets, such as mortgages and business loans. One might say that the net carry cost of debt, in this case, is negative. To the extent that the federal government invests in programs designed to enhance productivity (for example, health care and infrastructure), the same thing might apply to the national debt, which, as explained above, is willingly carried by investors at relatively low yields.

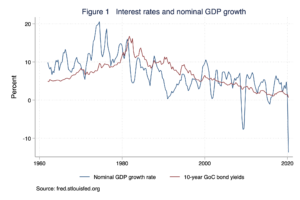

But even if government expenditures do not generate a high pecuniary rate of return, the federal government may still be in a position to carry its debt at an effective negative rate. This would be true, for example, if the interest rate on the national debt was on average less than the growth rate of the economy, or, as the condition is expressed in more technical terms, if r < g. It follows as a matter of simple arithmetic that if r < g, the government is in position to run a primary budget deficit indefinitely. That is, the effective carry cost of the debt is negative, even if the interest rate on the debt is positive.[6] Figure 1 shows the history of r and g for Canada.

Monetizing the debt

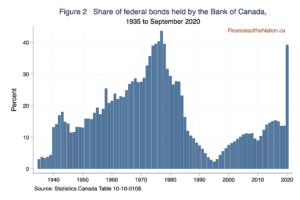

The average interest expense of the federal debt is influenced by the composition of the debt between currency, reserves, bills, notes, and bonds. The composition of the debt is determined in part by monetary policy. In particular, when the BoC purchases GoC securities, it is in effect swapping lower-yielding reserves for higher-yielding GoC securities (this is sometimes called “monetizing the debt”). The composition of BoC liabilities between reserves and currency in circulation is determined by the demand for currency, which can be thought of as a zero-interest government security.

The recent increase in BoC holdings of GoC securities is currently in the form of interest-bearing reserves. The implication of this is that private banks are now holding large quantities of interest-bearing reserves that are, to a first approximation, not much different from interest-bearing GoC securities. In short, the “monetization” of debt in present circumstances is not the same as in the past—see figure 2—where reserves are typically converted into zero-interest securities (currency).

Exactly how large of a primary deficit the government can run (say, relative to GDP) depends on the debt-to-GDP ratio. The debt-to-GDP ratio is not determined by the government; it is determined by the market demand for debt, which in turn depends on a host of factors, including the structure of interest rates, which are themselves determined or influenced by the BoC. An increase in debt obviously increases the numerator of the debt-to-GDP ratio. But how the debt-to-GDP ratio responds to an increase in debt depends on the denominator too. It is possible, for example, that an increase in debt causes the price level to rise by an even higher amount, which, for a given level of real GDP, would cause the nominal GDP to rise and the debt-to-GDP ratio to fall. There is presumably a limit to how much the market is willing or able to absorb in the way of GoC securities, for a given price level (or inflation rate) and a given structure of interest rates. However, no one really knows a priori how high the debt-to-GDP ratio can get. We can only know where the limit is once we get there.

Inflation

The purchasing power of nominal wealth is inversely related to the price level. That is, a higher price level means that your money buys fewer goods and services. Inflation refers to the rate of change in the price level over time. It is helpful to keep in mind the difference between a change in the price level (a temporary change in the rate of inflation) and a change in inflation (a persistent change in the rate of inflation). It is admittedly difficult to disentangle these two concepts in real time, but it is nevertheless important to make the distinction.

The amount of nominal government “paper” that the market is willing to absorb for a given structure of prices and interest rates is presumably limited. A one-time increase in the supply of debt that is not met by a corresponding increase in demand is likely to manifest itself as a change in the price level or the interest rate, or both. An ongoing issuance of debt that is not met by a corresponding growth in the demand for debt is likely to manifest itself as a higher rate of inflation. How the interest rate on GoC securities is affected depends mainly on BoC policy.

As long as inflation remains below a tolerable level, there is little reason to be concerned about a growing national debt. As with a firm that finances itself with convertible debt, the prospect of involuntary default is never a concern for a government. Of course, in reality, a firm that exercises its conversion option is likely to experience share dilution. Similarly, a government that exercises its power to monetize debt is likely to experience a jump in the price level. In both cases, however, the resulting dilution is likely to have more to do with the underlying events triggering the option than with the conversion itself. A company or government that suddenly finds itself under fiscal pressure (for example, because of an emergent rival or a war, respectively) will have to deal with that pressure one way or another, whether through cost-cutting measures, outright default, or dilution.

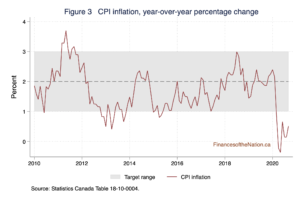

There is the question of what might be expected to happen if inflation rises persistently above a tolerable level. In Canada, the government and the BoC jointly determine an inflation target. This target is currently set at 2% per annum, with what could be interpreted as a tolerance band of 1 to 3%. If inflation were to increase and remain persistently above 3%, the BoC might be obliged to cut back on its purchases of GoC securities. The effect of this would be to put upward pressure on bond yields. Higher interest rates would reduce private sector wealth and increase the cost of borrowing, both of which would serve to reduce private sector spending, slowing economic growth. Higher interest rates would also serve to increase the government’s carry cost. This, in turn, could result in a set of government austerity measures that might slow economic growth, similar to the episode Canadians experienced in the early and mid-1990s.

Of course, all this might be avoided if the pace of debt issuance is slowed beforehand. But as mentioned above, there is no way of knowing beforehand just how large the national debt can get before inflation becomes a concern. Since the financial crisis of 2008-09, the consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate has spent most of its time nearer the lower part of the target band of 1 to 3%—see figure 3. All we can say for now is that inflationary pressures appear to be contained. It would be wise, however, for the government to have a plan in place to deal with this contingency should it arise. The plan might allow for inflation to temporarily overshoot the upper band of the target for a period of time as tax and spending legislation is recalibrated.[7]

COVID-19

The recession induced by the COVID-19 pandemic differs in some ways from those induced by monetary-fiscal contractions or asset-price collapses. In these latter cases, private sector spending tends to decline far in excess of what might be justified by any change in underlying fundamentals. The COVID-19 shock, in contrast, has induced a contraction in some sectors of the economy that serves a clear social purpose—namely, preventing the spread of the virus.

A fundamental shock in one sector should naturally lead to changes in the level of economic activity in other sectors. While some sectors may even expand, aggregate output on net is likely to decline. To the extent that this rearrangement of activity constitutes a desirable response to the pandemic shock, fiscal stimulus designed to boost overall aggregate demand is not in order.

On the other hand, a shock of this nature also disrupts and generally tightens credit conditions. An uncertain economic outlook naturally leads individuals and businesses to cut back on their spending to build precautionary savings. To the extent that this fear is self-fulfilling, some fiscal stimulus may be in order.

But even absent the need for a fiscal stimulus, it seems clear enough that social insurance is in order. For example, programs such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which were designed to maintain the income of those who suffered income losses because of the pandemic shock, are something that most voters would likely have wanted for themselves if they were so afflicted. To the extent that aggregate output declines and to the extent that income support is financed by a one-time increase in the national debt, the result is likely to be a one-time increase in the price level.

In other words, Canadians should prepare themselves for the possibility of a temporary burst of inflation. To be clear, a higher price level is not inevitable since, as explained above, much depends on how the demand for GoC securities responds going forward. But should inflation breach the 3% level, this will not necessarily be a sign to tighten monetary or fiscal policy. The higher price level in this case should be understood as the mechanism through which purchasing power is redistributed across individuals over the course of the pandemic.[8]

[1] See, for example, Tobin (1950, 1986).

[2] See https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2017/02/staff-working-paper-2017-5/.

[3] Repo, which is short for “sale and repurchase agreement,” is a short-term collateralized lending arrangement in which the party needing cash sells a security and agrees to repurchase it the next day. If the repurchase fails to occur, the creditor keeps the security.

[4] Of course, this statement rests on the presumption that the BoC must ultimately support the Department of Finance in its operations.

[5] Federal debt is not net wealth to the extent that people hold it in anticipation of higher future taxes; see Barro (1974).

[6] The primary budget deficit does not include the interest expense of the debt.

[7] I should like to emphasize that “austerity” need not (and should not) be imposed on those most vulnerable in society. Overall program spending need not be cut; that is, growth in spending can be slowed, with funding shortfalls allocated to sectors of the economy that are better able to absorb the shock.

[8] That is, while the price level rises for everybody, those receiving money transfers still come ahead. The overall cost of living has to rise because output is lower. Those who do not receive transfers lose purchasing power. The effect is to transfer purchasing power from the fortunate to the unfortunate. Incidentally, a higher price level will serve to increase the nominal GDP—the effect of which will be to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio.