Robin Boadway, Queen’s University

Note: This Commentary has been updated on November 3, 2020 to correct an error in the marginal tax rate calculations reported in Figure 1.

The Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) is a bold step in the delivery of pandemic-related aid to self-employed and gig workers, who are poorly served by Employment Insurance. Advocates of reform to Canada’s income transfer system will find much to like about the CRB, and some may wish to make the program, or something like it, a permanent feature of Canada’s social safety net. However, there are likely to be substantial enforcement and implementation issues with the program, as well as problems around fairness. As currently designed, the CRB is not a good template for a guaranteed basic income for Canada.

The Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) is one component of a suite of temporary measures introduced by the federal government to replace the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). In addition to relaxed eligibility requirements for Employment Insurance (EI), three new measures have been enacted to support EI-ineligible workers whose employment income has been affected by the pandemic. The CRB primarily targets self-employed and gig economy workers, while the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit helps those unable to work due to COVID-induced sickness, and the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit assists caregivers.

Is the CRB “EI for the self-employed?”

The CRB represents an innovative approach to income support. Even though it is being touted as a program to extend EI to the self-employed, its structure and delivery are different from EI’s. Like the CERB, the CRB will be administered by the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Income support through the CRB is not contingent on job loss, and benefits are income-tested, although they only begin at a relatively high income level.

In these ways, the CRB has similarities to a guaranteed basic income of the sort that many analysts and politicians have advocated for in recent years.[1] Although the CRB is temporary and pandemic-related, it is natural to ask whether a CRB-like program should be made a permanent feature of Canada’s social safety net and, if so, what purpose it should serve—insurance or income support—and how it should be designed.

Eligibility

The CRB has features of both EI and a guaranteed basic income, but it is different from both. Applicants for the CRB are eligible if they (1) earned at least $5,000 in the previous 12 months or in calendar-year 2019, (2) had a reduction in income of at least 50% due to COVID-19, (3) are seeking work, and (4) are available for work (unless they are enrolled in a training program). Those eligible must apply to the CRA for the benefit for a two-week period, and can apply up to 13 times (for a maximum of 26 weeks). Eligibility is based on self-attestation; applicants have an obligation to provide supporting information if requested. Successful applicants receive $500 per week, for a maximum amount of $13,000. Payments are taxed back at a 50% rate on income in excess of $38,000. For a person receiving the maximum $13,000, the CRB is fully taxed back when income reaches $64,000. The tax-back occurs after the end of the year, when incomes are reported for tax purposes; repayment must be made to the CRA.

Incentives

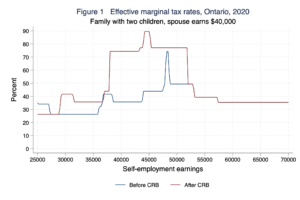

The incentive effects in the CRB and EI also differ. These differences stem from the effective marginal tax rate produced by the two programs at various income levels. The concept of an effective marginal tax rate refers to the amount of an additional dollar earned that is lost either to taxes or to a reduction in cash benefits. A high effective marginal tax rates creates stronger work disincentives than a low effective marginal tax rate.

The CRB is reduced by 50 cents for each additional dollar earned. When combined with the personal income tax rate, this implies that effective marginal tax rates rise to around 70% in Ontario (15% federal tax plus 5.05% provincial tax plus 50% CRB tax-back). Comparable effective marginal tax rates apply in other provinces.

But this calculation does not account for the fact that CRB benefits are taxable, or for the tax-back of existing benefits, including the Canada Child Benefit (CCB) and the Goods and Services Tax credit. Figure 1 shows the schedule of marginal tax rates as a function of earned income for married CRB recipients with two children for Ontario in 2020, when the maximum possible CRB benefit will be $7,000.[2] When all benefit clawbacks are incorporated, marginal tax rates exceed 75 percent for all income levels between $38,000 and $52,000. Given the high effective marginal income tax rates, and given that the workers targeted by the CRB have considerable discretion over their work intensity, work disincentives are significant in the CRB tax-back range.

For most self-employed individuals, the earnings levels at which at the CRB is taxed back are too high to be applicable. As Tammy Schirle and Mikal Skuterud previously reported at Finances of the Nation, more than half of those in self-employment had earnings below $23,000, even before the pandemic. However, for a significant minority of potential self-employed CRB recipients, the disincentive effects will be strong.

Administration and enforcement

The self-reporting feature of CRB raises difficult administration and enforcement issues. Applicants must attest that their pre-application income was above the threshold amount and that it fell by 50% as a result of the pandemic. In principle, pre-application income should be verifiable ex post, but a drop in income is more difficult to prove (since incomes could have fallen for reasons other than COVID-19). Many self-employed workers receive income from sources that are not subject to third-party reporting. Previous research has suggested that reported income can be quite sensitive to tax rates for the self-employed. Moreover, verifying that self-reporting applicants are searching for work and willing to accept jobs that are offered is challenging, to say the least.

In short, the CRB as currently designed should not be viewed as an effective extension of the EI program to the self-employed. The incentive effects differ, and folding the CRB into the EI will create new administrative and enforcement issues.

Is the CRB a guaranteed basic income for the self-employed?

Addressing the challenges described above to permanently integrate the CRB into EI to provide “employment insurance for the self-employed” would be very difficult. Differences between the treatment of employed workers under EI and the self-employed under the CRB are inevitable. One could imagine allowing self-employed workers to enrol in EI by paying a contribution rate equivalent to the employee-employer rate, as some European countries do. But the concept of unexpected job loss that leads to eligibility for benefits by employees is not relevant to self-employed individuals, for whom the intensive margin is more relevant than the extensive one. Eligibility for insurance would have to be triggered by some criterion of earnings loss, along the lines of CRB eligibility.

For these reasons, it may be more fruitful to think of insurance provided to the self-employed as being income or earnings insurance rather than employment insurance. In that sense, the CRB is more like a guaranteed basic income for the self-employed.

A guaranteed basic income can be viewed as a form of income insurance provided to all residents. One could think of the CRB as being the piecemeal introduction of a guaranteed basic income for a subset of the population, just as OAS/GIS is a form of basic income for seniors and the CCB is akin to a basic income for families with children.

Despite their similarities at first glance, the CRB actually has many features that distinguish it from a guaranteed basic income for all residents.

First, the eligibility conditions for the CRB are much more stringent than those favoured by many proponents of a guaranteed basic income. Eligibility for a guaranteed basic income is contingent on income, and possibly on family size. In contrast, the CRB requires participants to be seeking work and accepting jobs that are offered, and to have experienced a 50% decline in income. Perhaps most important, the benefit structure of the CRB, if extended to the entire population, would mean a much more expensive program than is typical for guaranteed basic income proposals. If the income-loss eligibility conditions of CRB were eliminated so that it becomes available to all Canadian residents, and if the 26-week upper limit were abolished, all persons with annual incomes up to $38,000 would receive a basic income of $26,000 per year before tax ($500 per week). With a tax-back rate of 50%, payments would be phased out only at an income level of $90,000. Effective marginal tax rates of 70-80% would apply on incomes between $38,000 and $90,000. This would cost much more, and entail much higher marginal tax rates, than the guaranteed basic income programs that have been typically proposed in Canada, where tax-backs begin with the first dollar earned and effective tax rates are in the order of 50-60%.

Conclusion

As currently designed, the CRB is neither fish nor fowl. The program cannot practicably be combined with the EI program, nor can it serve as a fair and effective form of a guaranteed basic income for self-employed people.

If the CRB is to be folded in to EI, significant changes would have to be made so that the self-employed were not treated more generously than employees. This would require, among other things, a comparable contribution rate and harmonized treatment of earnings, so that the same tax-back provisions apply to both employees and the self-employed.

If the CRB is to become a kind of guaranteed basic income, one might ask why it should be available only to the self-employed and not to other members of society, such as the working poor or the long-term unemployed. Extending the CRB to all persons would entail the elimination of employment conditions and a reduction in the generosity of the tax-back provisions, which would in turn reduce administrative costs and enhance affordability.

The CRB is ill-suited to provide permanent employment insurance to self-employed people, while the creation of income insurance (that is, a guaranteed basic income) for this group would be difficult to implement and would pose challenges around fairness, affordability, and work incentives. For these reasons, the CRB in its current form would not be a well-designed addition to Canada’s social safety net. Those who want to make the CRB, or something like it, a permanent feature of Canada’s social safety net must clearly show how these issues can be resolved.

[1] See, for example, Hugh Segal, “Guaranteed Annual Income: Why Milton Friedman and Bob Stanfield Were Right” (April 2008) Policy Options 46-51.

[2] The figure was created using Kevin Milligan’s Canadian Tax and Credit Simulator.