Kyle Hanniman and Trevor Tombe

This commentary examines recent differences in growth rates and interest rates at the federal and provincial levels in order to estimate the future paths of public-sector debts. The results provide a novel perspective on a recurring theme in Canada’s debt sustainability debates—namely, that Ottawa is in a better position than most provinces to stabilize its debt-to-GDP ratio.

According to recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund, Canadian government fiscal responses to the pandemic amount to nearly 19% of gross domestic product (GDP) when both direct and liquidity supports are included. Large government deficits are an appropriate response to this unprecedented shock. But in the long run, the additional debt creates significant risks. So it is healthy that debates over the ideal path and pace of fiscal consolidation have begun.

There is an unavoidable arithmetic behind the evolution of public debt. It is driven, in large part, by the relationship between the economy’s long-run growth rate and the long-run interest rate on government borrowing. Indeed, where economists and policy analysts stand on debates about fiscal consolidation often depends on their expectations about this relationship. If economic growth exceeds interest rates, perpetual deficits are in principle sustainable. But if interest rates exceed growth rates, debt-to-GDP ratios are likely to increase quickly, which will force governments to raise taxes or cut spending, or both, to stabilize public finances.

It is impossible to know where growth–interest rate differentials will go. Traditional models of fiscal sustainability assume that interest rates will exceed growth rates in the long run. However, the empirical record often tells a different story. Indeed, over the past two centuries, growth rates have exceeded long-term interest rates in most developed countries in most years (Mauro and Zhou 2020), and many expect this pattern to hold well into the future.

But almost all analyses of growth–interest rate differentials have focused on the national level. Such an approach is very limiting for a country like Canada, where subnational governments undertake unusually high levels of spending, taxation, and borrowing.

This commentary examines recent variations in growth–interest rate differentials at the federal and provincial levels, and uses the data to estimate the future paths of public-sector debts. The results provide a novel perspective on a recurring theme in Canada’s debt sustainability debates—namely, that Ottawa is in a better position than most provinces to stabilize its debt-to-GDP ratio (Hanniman 2020, Parliamentary Budget Office 2020, Tombe 2020).

Analysis and results

It is important to look at provincial and federal finances separately. Provinces pay higher borrowing costs, are more vulnerable to credit shocks, and depend on a narrower (and thus more volatile) set of revenue streams. All of these factors put them at greater risk of unfavourable fiscal conditions.

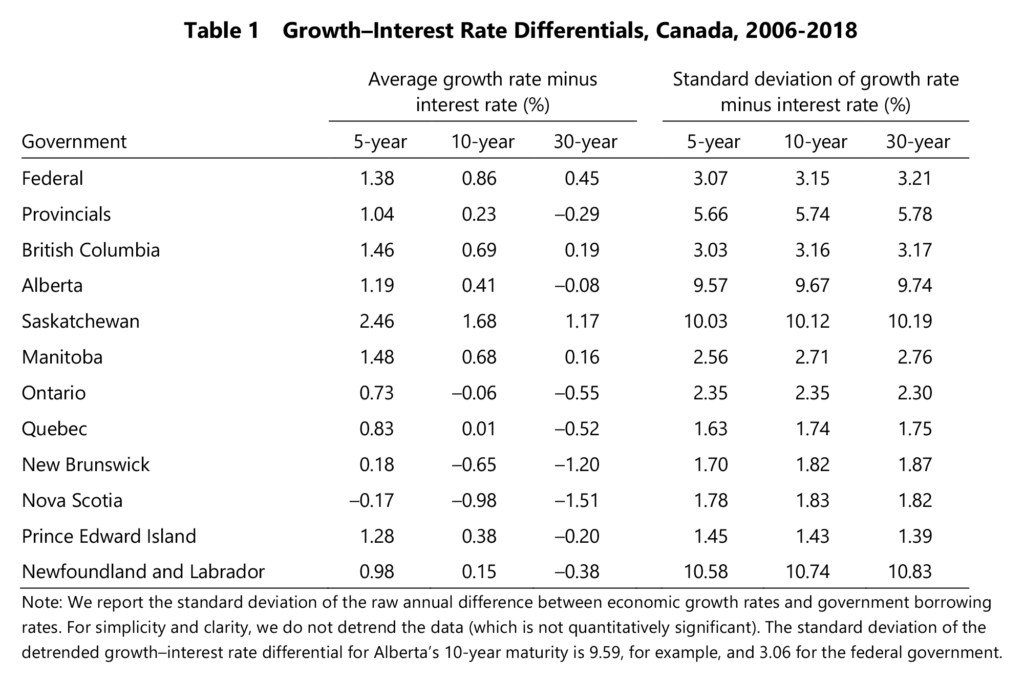

To quantify the potential scale of future risks, we use data from the Bank of Montreal for 2006 to 2018. These data are not just simple interest rates. They are the underwriter’s constant maturity estimates of the interest rates a province would pay if that province were to issue a domestic-currency bond on a given day. We then take daily averages for the year. We focus on 10-year bonds because it is a standard maturity in these analyses, and the most liquid bond maturity for provinces. We also display 5-year and 30-year maturities in table 1.

A few notable patterns stand out. First, some good news: The federal government enjoys strong fiscal fundamentals, with economic growth exceeding interest rates by an average of 86 basis points over the sample period. More good news: Although the provinces, with the exception of Saskatchewan, all have lower growth–interest rate differentials, most still have higher growth rates, on average, than their long-term borrowing rates. Our enthusiasm about this second piece of good news is tempered, however, by the fact that the rate differentials for Ontario and Quebec, which accounted for roughly two-thirds of the provincial bond market in 2019, are close to zero. Only Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have interest rates that are significantly higher than growth rates.

These data also reveal causes of concern. While the overall provincial difference is positive, the variance in the growth–interest rate differential is notably higher. Overall, the standard deviation of the difference between growth rates and interest rates is 5.7% for provincial governments but only 3.15% for the federal government. Not surprisingly, this volatility is particularly pronounced among the three oil-producing provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

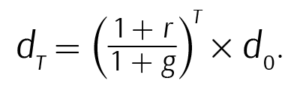

This volatility matters because it creates fiscal risks for provincial governments. To illustrate this clearly, consider how growth rates and interest rates matter for debt levels. For simplicity, assume that interest rates and growth rates are constant, and also assume that governments run balanced primary budgets in every year (that is, revenues cover all program expenditures). In this case, debt in T years will be

But if interest rates and growth rates are volatile, a whole range of potential future debt levels become possible. Debt levels today, after all, would rise or fall depending on the sequence of future interest rates and growth rates.

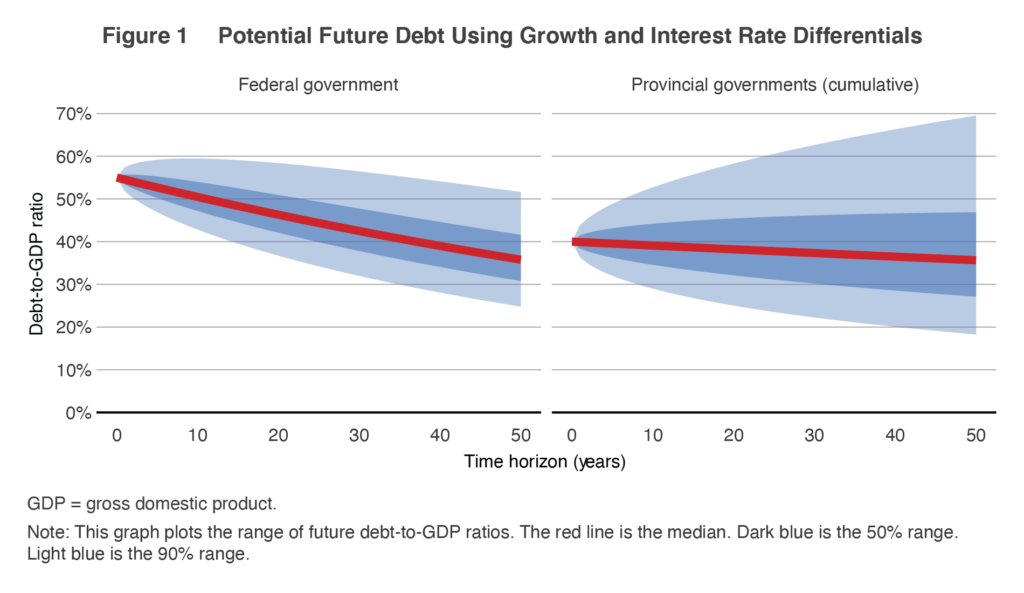

It is straightforward to visualize this. In figure 1, we simulate the path of future government debt-to-GDP ratios assuming that the ups and downs of future economic growth rates and borrowing costs are distributed as they are in the recent historical data. To focus on the effects of this volatility, we continue to assume that governments run balanced primary budgets. To be clear, this abstracts from the longer-run fiscal pressures that governments may face, and for some provinces a balanced primary budget is a potentially optimistic scenario. The wide range of possible outcomes (particularly at the provincial level, where the average difference between economic growth rates and interest rates is 5.74%) shows how volatility in these rates matters for debt levels over time. If economic growth disappoints or if interest rates rise, debt levels will rise as well. Figure 1 illustrates a range of potential futures for provincial and federal debt.

It is clear that provincial governments face a much wider range of potential future debt levels, and thus greater risk exposure, than the federal government. Over the span of 50 years, provincial governments have a 90% confidence range of debt levels being between 20% and 70% of GDP. In contrast, the federal government has a much tighter range, between 25% and 50% of GDP. Even if provinces balance their primary budgets, there is a relatively strong likelihood that debt levels will grow larger over time.

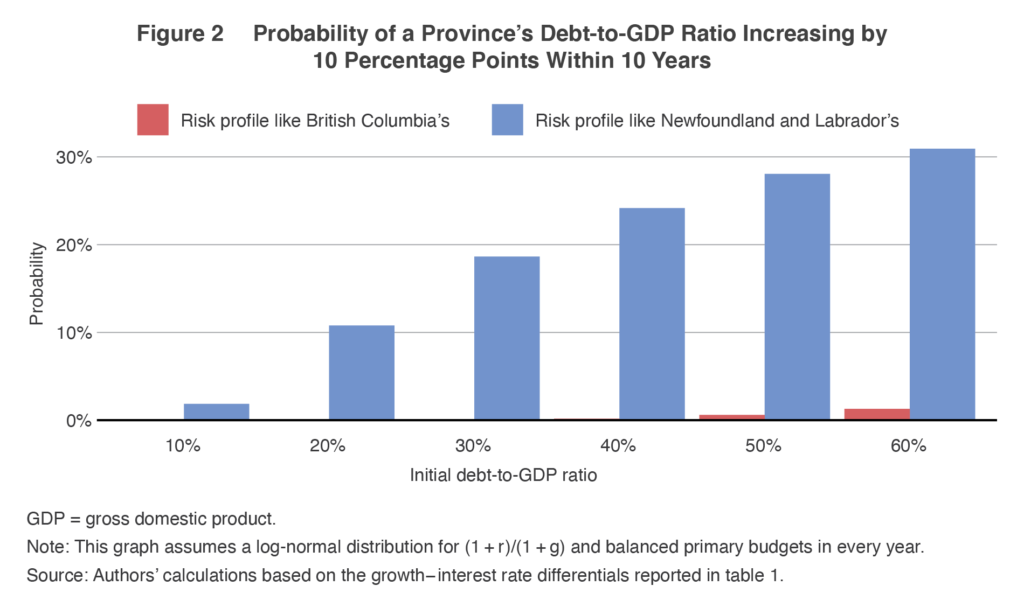

There are also important differences among provinces. Higher current levels of debt mean that future debt levels are more sensitive to changes in underlying economic growth rates and interest rates. That is, high-debt provinces are exposed to greater fiscal risk.

The differences between government debt levels are large. Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, may come out of the COVID-19 shock with debt levels approaching 60% of GDP, compared with roughly 20% that may be seen in British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. In figure 2, we use the underlying growth–interest rate differentials for British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador to illustrate the probability that a province will experience a 10 percentage point increase in its debt-to-GDP ratio within 10 years, even if the province balances its primary budget every year. (Again, most provinces are planning for post-COVID deficits that will further add to debt. Our purpose here is to isolate the effect of volatility from borrowing to cover program expenditures.) For a high-debt province facing elevated risks, we find the odds are nearly one in three that its debt will rise by a further 10 percentage points of GDP within 10 years. In contrast, for a low-debt province facing lower risks, we find the odds of this happening are nil.

Policy implications

What does all of this suggest for policy? A few things.

Sustainable budget deficits depend on the difference between economic growth rates and interest rates. Given expected provincial debt-to-GDP ratios for 2020-21, and presuming that the growth–interest rate differentials above hold in the future (a strong presumption made here for illustrative purposes), we find that most governments can sustain modest primary deficits. But the underlying volatility of economic growth and borrowing rate differences exposes governments to risks. Even when provinces run balanced primary budgets, there is a roughly 40% probability of aggregate provincial debt levels rising in the long run.

This does not imply that large fiscal adjustments are required today. Provinces can afford to adopt a slower path to fiscal consolidation than was taken in the 1990s. Interest rates are lower and are likely to remain low, thanks to relatively accommodating monetary policy in the short term and to demographic factors in the long term.

But whatever the optimal path to fiscal consolidation may be, it clearly differs across levels of governments. Many have noted the additional costs that the provinces will incur because of their aging populations and health-care responsibilities. Far less has been said about their less favourable and more volatile growth–interest rate differentials, and even less about differences in these risks across provinces. However, both dynamics lead to the same policy conclusion: the provinces will have to run more conservative fiscal policies than Ottawa in order to guard against fiscal risks and to ensure their fiscal sustainability. These differentials should be front and centre in discussions about provincial fiscal sustainability.