Globe and Mail columnist Andrew Coyne recently took to Twitter to elaborate, with multiple charts, on his recent column about the woes afflicting the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board. The tweets and charts below are reprinted with his permission.

My latest, on the growing mess at the CPP, flagship of the “Canadian model” of pension investing: spend billions of dollars every year to basically track the market. Maybe it pays off in the long run; maybe not. But meantime the managers make a fortune!

I said what I could in the space I had, but there’s just no substitute for a good chart to really make a point. So just to drive home what’s going on at the CPP Investment board, I’ll post a few here…

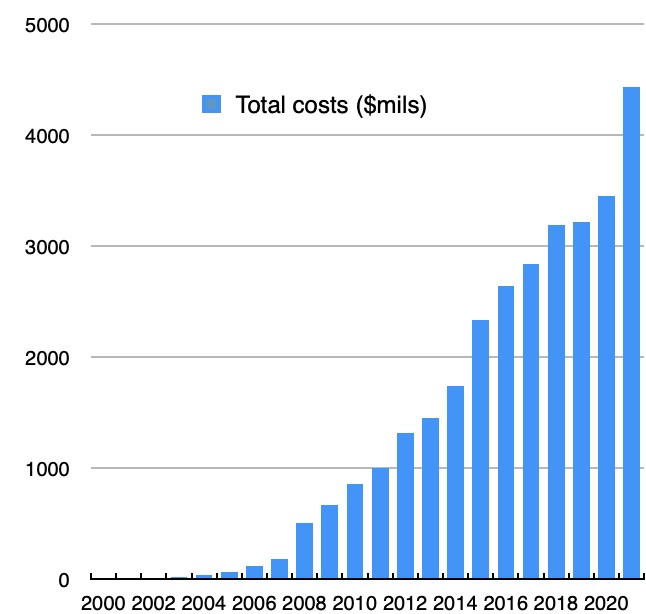

First, total costs (combining operations, transactions costs, and external management fees). Since 2000 they’re up a thousand-fold: from $4 million to $4.4 billion.

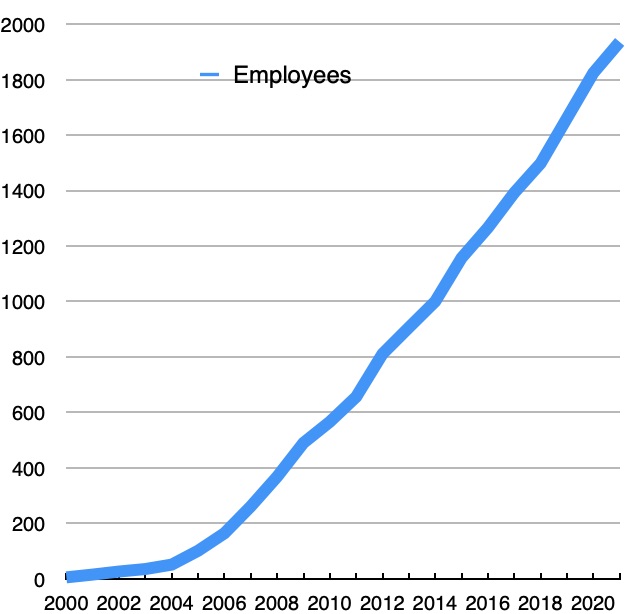

Part of what’s driving the explosion of costs is staffing: the number of employees on the CPPIB’s payroll has increased from 5 in 2000 to 1936 last year.

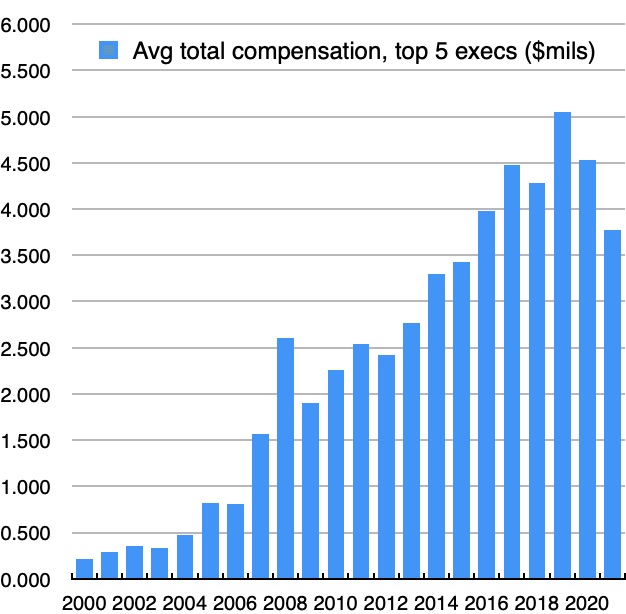

But part of it is how much they’re paying them — especially at the top. And what’s driving both is the switch in investment strategy: from the passive, “buy the index” strategy the fund was required to follow at its inception, to the active management strategy it later adopted

In 2006, just before the switch, the five highest-paid executives at the CPPIB made about $800,000 apiece, on average. By 2019 it was north of $5 million.

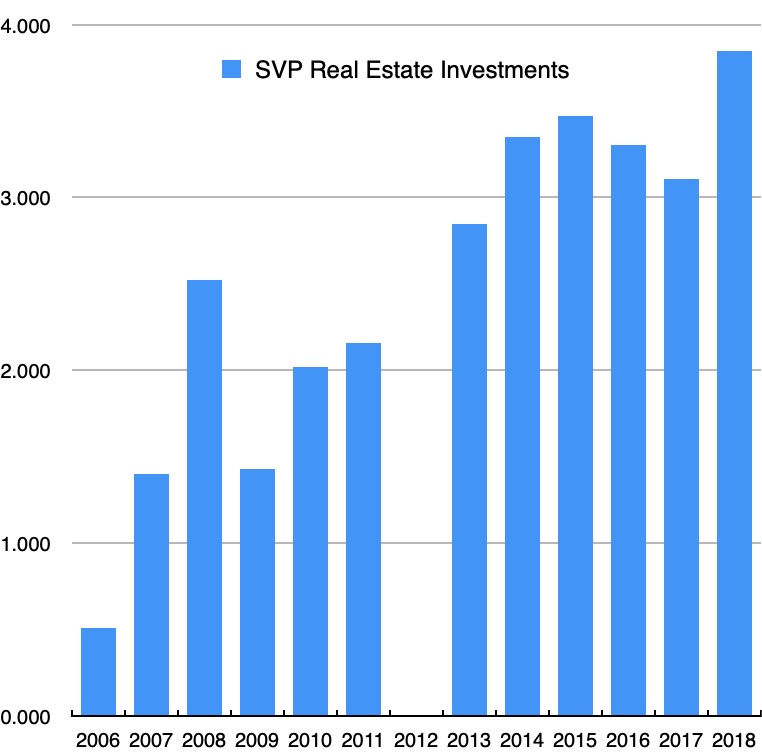

For managers whose career straddled the switch, it must have felt like winning the lottery. Here’s an example: the CPPIB’s former SVP of real estate investments, Graeme Eadie. In 2006, his first year at the board, he made a little over $500K in salary, bonus and benefits…

By the following year, his compensation package had jumped to $1.4 million. It peaked at $3.85 million, before he retired in 2018.

But of course, the CPPIB had to hire all these people, and pay them all that money, because it was investing in such hard-to-find assets. Never mind conventional stock-picking: “active management” in this case meant transforming the CPPIB into an oversized private equity fund…

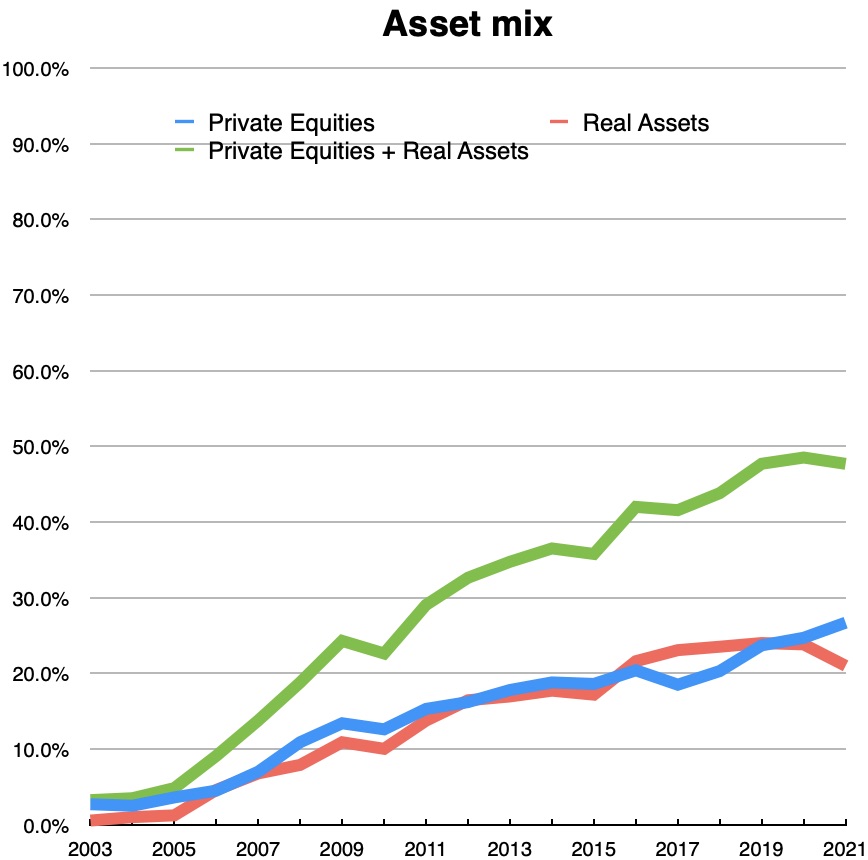

What began as a modest dip of the toes into private equity — the fund thought it might have as much as 10 per cent of its assets in PE by 2011 — has turned into an all-out cannonball plunge. The CPPIB now has more than a quarter of its assets in PE …

Add the 20%-plus of its portfolio allotted to real assets — things like shopping malls and infrastructure projects — and nearly half the CPP fund is tied up in illiquid assets of uncertain value.

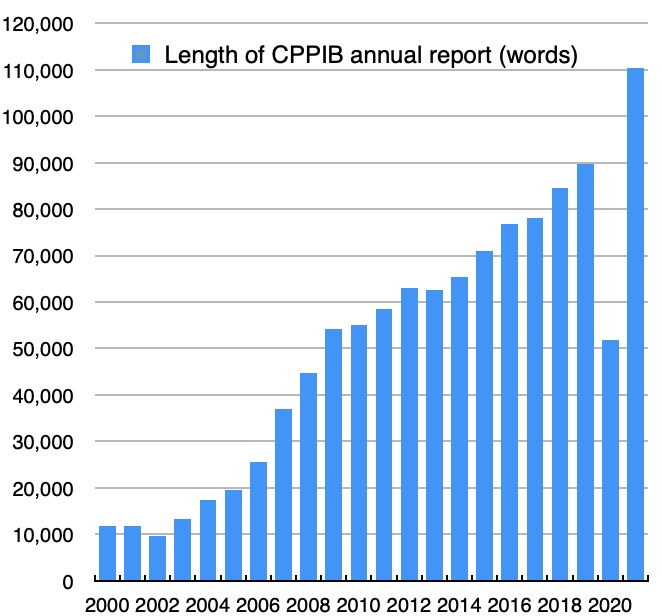

So: rising staff numbers, rising compensation, rising costs. Oh, and my favourite indicator of bloat: the length of the CPPIB annual reports, which this year hit a record 110,000 words — ten times as long as in the early 2000s. You can imagine what it’s like to wade through…

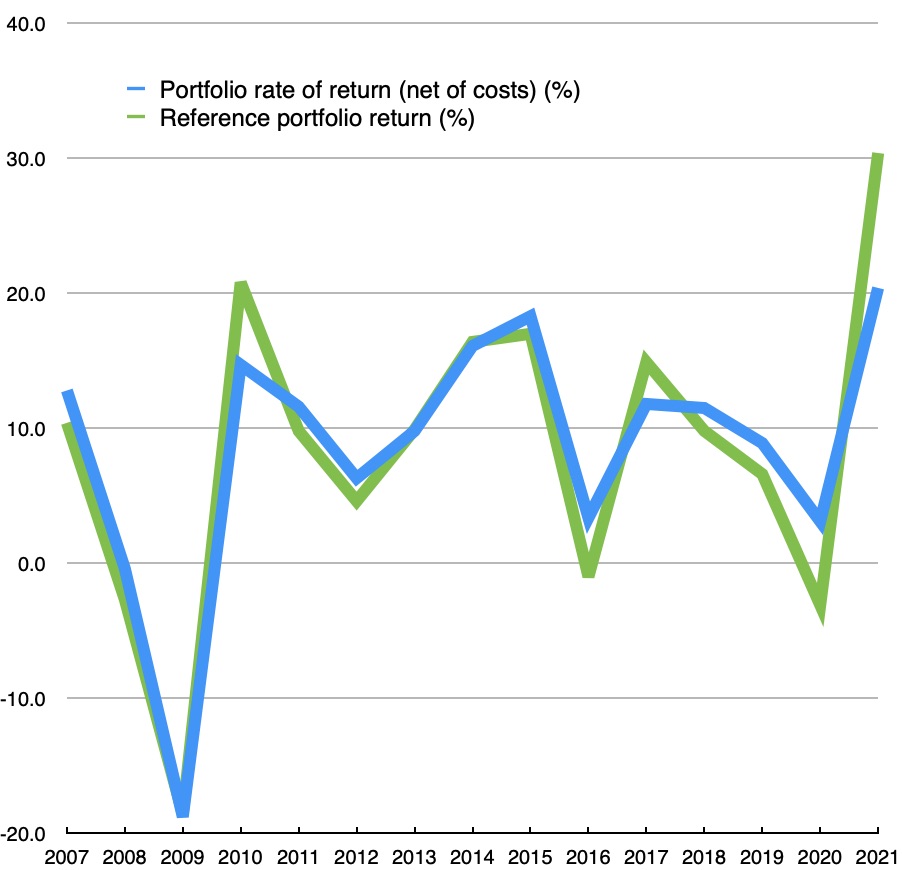

All told, the CPPIB has spent nearly $30 billion since the switch to active management. And the result?

Basically most of whatever premium the CPP might have gained from all of this wheelspinning has been eaten up in costs — including the gigantic pay packets for its managers. But who’s going to call them on it?

Not the managers, certainly.

Not the CPP’s millions of contributors: they have no choice but to keep paying into it…

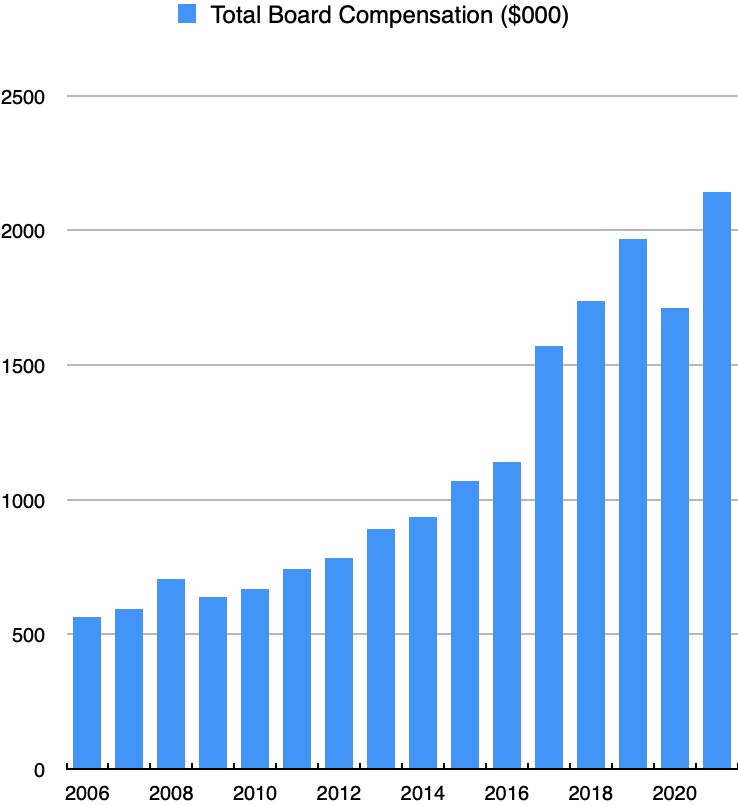

The board of directors? Maybe. But they seem content with things as they are — possibly because their pay has skyrocketed along with everything else. Since 2006, total compensation for the board’s 12 directors has nearly quadrupled.

And who do the board of directors answer to? Good question.

Overall responsibility for the CPP is shared between the federal and provincial governments, neither of whom may interfere with directors’ decisions…

Which is fine, but … who then holds them to account for the fund’s performance? It’s not like somebody can launch a takeover bid for the CPP.

One final point: the CPPIB’s 2021 annual report lists “personnel costs” at $938 million. For 1,936 employees. You do the math.

Nice work if you can get it.

Coda: My alternative? I’m glad you asked. The alternative is how Nevada achieves great results with a very limited investment staff.

Consider the following quote from a second article noting the state is hiring its second investment manager after achieving great success with only one.

“The (Nevada) fund has returned 9.6% annualized since its inception and over the past 10 years, and it has returned 10.9% and 10.6% over the past five and three years, respectively.”