COVID-19, this microscopic but relentless bug, seems to have upended just about everything. History provides no perfect analogy for what has turned out to be a global health, social and economic catastrophe. The virus has altered our lives and shaken us out of our normal ways, forcing us all to weigh what matters most, as well as exposing and magnifying our collective strengths and, with sometimes fatal results, our collective weaknesses. It continues to test our trust of one another, of our governments and of science. It’s testing the robustness of our institutions and exploiting their frailties. Has it also upended the fiscal approach that has shaped federal policy in Canada since the mid-1980s?

This is the question asked in a recent Finances of the Nation commentary: Has the Liberal government abandoned aversion to debt and taxes as the organizing principle of fiscal policy? Put another way, it asks whether we are on the eve of a shift from austerity light (and sometimes not so light) to a more expansive role for government and, if so, how expansive will that be?

The short answer is we don’t yet know, and while this uncertainty has apparently caused consternation among many, we should welcome it and use it to our advantage to have a long overdue debate about the role of debt and taxes in building the Canada we want.

The Liberals had already loosened the reins a bit when in 2015 they discarded the fiscal anchor of annual balanced budgets that had been in play since the mid-1990s and announced a willingness to run deficits to address priorities. Still, the Trudeau government kept deficits to less than one per cent of GDP prior to the pandemic, did not allow debt to grow relative to the size of the economy, and indicated its intent to get to balance sooner or later. Nonetheless, the deficit hawks began to hover.

Then came the COVID-19 crisis and something of a fiscal truce. Gone were the calls for restrained spending, small government and balanced budgets. Across the political spectrum, governments, and especially the federal government, were spending borrowed money. Polls indicated Canadians were generally on board, more concerned about the virus and its economic/human toll than the debt. A majority wanted government to spend whatever it took to keep people safe and whole, and to avoid even worse economic consequences. Across the political spectrum, observers of government — including many who had been lambasting the Liberals for their pre-pandemic deficits — were for this brief moment welcoming or at least tolerating active government, deficit spending and increases to the public debt.

However, the truce, it seems, is over. Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s November fiscal update indicated that the federal deficit could reach $400 billion this year. She also signalled that additional spending is coming – up to $100 billion in stimulus to kickstart recovery and “to build back better” – to address the cracks in the system that the COVID-19 crisis exposed and exacerbated, as well as to up our game on climate change, nature loss, Indigenous reconciliation and racial justice. But what seems to have triggered concern even more than the numbers was the minister’s decision to delay the introduction of a fiscal anchor to constrain the government’s budget choices.

Headline after headline announced that the government had become unmoored, set adrift. Op-eds argued that without a fiscal anchor and some clearer indication of just when we might expect to return to balance, we were taking incalculable risks.

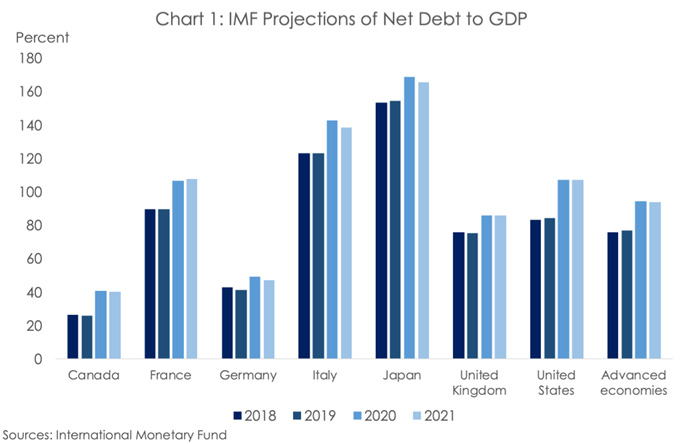

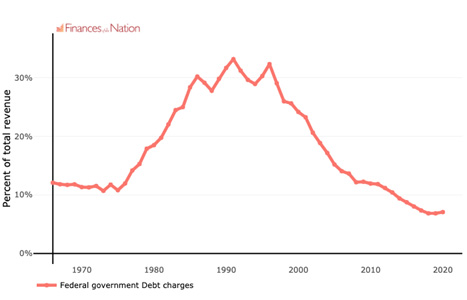

But frankly, why the rush, what’s the urgency? As Chart 1 shows, our federal government’s fiscal situation is the envy of most rich countries. It was before COVID-19 and it is now. As for our current record-beating debt levels, because interest rates are so low, the government will pay less in debt charges for this fiscal year than had been forecast before the pandemic. As Chart 2 reveals, interest costs as a share of the total federal revenue are lower than ever. And inflation has been persistently under the two per cent target.

With the need for more public spending, with borrowing being pretty much free and with no signs of significant inflation pressure, it would be arguably irresponsible not to borrow. Rising public debt is entirely manageable if interest rates remain low and particularly as the Bank of Canada continues to buy federal and provincial bonds as it has been doing at the rate of $5 billion a week. And as it has indicated, it will continue doing so as long as necessary, though at a slightly reduced rate.

Chart 2 : Debt Charges as a Share of Total Revenue

Our experience after the Second World War — when our debt level was well over 100 per cent of GDP — shows that we can tame such a debt over time without cutting spending, and come out much stronger for it. Of course, circumstances were different after the war. Taxes were much higher, for example, and economic growth much stronger, partly because governments were expanding health and education infrastructure to keep up with the demographic pressures triggered by the baby boom. But clearly, deficits and higher taxes were how we built the social union that we have allowed to fray for the past decades.

Simply, we have the time and the need for a long-overdue debate about what our fiscal approach should be once we are through the immediate emergency, and once we start to address the larger emergencies of climate change, nature loss, economic inequality and economic insecurity. That debate ought to begin with an assessment of how well we have been served by decades of austerity, light or otherwise.

The approach may have meant fiscal resiliency but as the virus made evident, that came at the expense of societal resiliency. COVID-19 has preyed on and magnified social and economic inequities, as well as exposed cracks in the system: our lack of preparedness; the tragedy of nursing homes; the human costs of prison overcrowding; the failure to eliminate chronic homelessness; and the constant exposure to risk and danger in public-facing work, where employers offer little or no protection.

The relief programs put in place were critical to containing the economic damage caused by the contagion, but they are also testament to the inadequacy of our existing social protections and automatic stabilizers. Employment Insurance, for example, covers too few of the unemployed and covers them inadequately. In other words, the pandemic has made inescapable the need for long-term investments in public health, housing, child care, long-term care, and income supports.

The overriding focus on limiting debt coupled with the reluctance to raise taxes has severely narrowed our sense of what is affordable and therefore what is possible. Numerous polls show that we generally want the same things we’ve always wanted: decent work; access to healthcare; child care; good education and training; financial aid when we are in trouble; a secure retirement; safe and livable communities; a healthy environment; and a fair and inclusive democracy. What has changed is that we are, it seems, less convinced that such a future is affordable. In short, federal fiscal policy centred on debt avoidance and tax reduction has reduced government’s footprint, ushered in an unprecedented upward transfer of wealth, and stunted our political imagination.

Canadian economist Jim Stanford has been leading the charge to open wide our window of possibility. That will mean getting over our aversion to deficit spending. He has been making the case that what’s needed right now is a level of ambition much like what we saw after the war, with strong federal leadership supported by an active central bank. Not only should we stop worrying about deficits, we should celebrate them, he says. “Yes, deficits will be huge in the coming years…. Public debt will soar past 100 per cent of GDP within a couple of years…; anything less than that would be a sign that government is literally not doing its job to protect Canadians from this crisis.” As long as we borrow in our own currency and largely from ourselves, we are in good shape. Nor, when we borrow from ourselves, do we “burden our children’s generation. ” Yes, they will pay the interest. but they will also receive the interest payments. They will also get better infrastructure, a cleaner environment, more affordable housing and livable communities. If we’re smart about it, we’ll issue long-term debt to lock in the low interest rates, which is what the IMF advises and what Canada’s finance minister has signalled.

So how much debt is too much? At what point will the sky fall, and chaos be unleashed? For a time after the financial meltdown, there seemed to be a simple answer. Influential research by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff purported to show that if debt grew to 90 per cent of GDP, economic growth would be put into reverse. Not surprisingly their work, and the notion of a debt tipping point, found its way into speeches and policies of conservative leaders anxious to reduce government’s footprint. This research reinforced the view that deficits and debt are the problem, while some version of austerity is the solution.

Not long after, three economists from Amherst University took apart the Reinhart and Rogoff study and found numerous errors. When the data were adjusted, it turns out that there is no magic debt threshold or if there is, it’s somewhere well north of 90 per cent. The corrected data continued to show a relationship between debt and growth, but not as strong as previously thought. Even countries at 90 per cent or higher showed some growth. Nor do their findings allow us to assume causality — does debt slow growth or does slow growth increase debt?

Perhaps most telling are three recent studies by the research arm of the IMF, each of which challenges the conventional fiscal wisdom that the IMF had itself done the most to promote. One of these studies concluded that the economic costs of austerity — putting aside for the moment the human costs — were far greater than the IMF had anticipated. In the years after 2010, when many countries, including Canada, opted for deficit reduction starting almost immediately after the great recession, the effect was in fact to slow growth, which in turn reduced government revenues, which in turn meant more deficits and debt.

Another concluded that the economic benefits of “neoliberal” policies designed to shrink or contain the size of government had been badly oversold, while the social and economic costs had been significantly underestimated, particularly with respect to the corrosive effects of increased inequality.

Yet another found no clear relationship between debt and economic growth. In fact, for advanced economies in good standing like Canada, the study comes to what it describes as the “unpalatable” conclusion that there seems to be no limit to how much debt a government can issue. The study found that over the long term, interest rates were lower than the economic growth rate, and this meant that carrying charges on the debt were affordable. Consider that Japan’s debt, which stands at about 250 per cent of GDP, hasn’t stopped it from spending more to deal with the pandemic — and it is not in chaos.

The study does offer a number of cautions and caveats. Of course, deficits matter: taking on a lot of debt has costs and risks, especially because of short-term interest rate volatility, and it is important that governments indicate clearly how they propose to assess and manage those risks. Of course, it also matters greatly what the borrowing is used for. Most economists would agree that there’s good debt and bad debt. It would be more productive to debate which is which than to wring our hands about getting back to balance.

Nonetheless, to ensure that what is being built is sustainable, and that the costs and benefits are allocated fairly, we will sooner or later also have to come to grips with our aversion to taxes.

Tax reform will have to be a central part of the mid-term agenda. In the midst of a recession, we must tread carefully, but some measures could actually contribute to growth now and have significant public support. For example: finally plugging the leaks and collecting what is already owed under existing tax rates, implementing an excess-profits tax to get at those companies, especially the “digital giants” whose profits soared during the pandemic, and doing more to tax the wealth of the very rich. In any case, essential to a just and green recovery will be fundamental tax reform to fix what’s broken, to reflect our changing world, and to ensure that those who benefit most from how things are pay the largest share for making things better. We need a tax system that can serve as the foundation for a more equal and sustainable Canada.

So yes, governments need to tell us what mix of taxes and borrowing they propose to pay for their plans and how they will manage the risks. But rather than starting with a top-down debt anchor that tells us what we can afford, we ought to be debating what we need, the future we want and the role of government in building that future. We cannot afford to have those debates short-circuited by deficit and tax phobia.

This post includes some material previously published here and here. Thanks to Duncan Cameron, Jordan Himelfarb and Andrew Jackson for their comments.