Livio Di Matteo, Lakehead University

Provincial governments across Canada face a conflict of interest surrounding the policy treatment of alcohol, tobacco and gambling. On the one hand, all provinces derive substantial revenues from “sin taxes” or from providing these goods and services through government monopolies. On the other hand, governments have a mandate to promote public health, all of which are negatively affected by alcohol, tobacco and gambling addictions. This commentary explores the conflict of interest surrounding sin taxes.

Government is often seen as a benign entity that provides important supports of health, education and social services and extends a helping hand to its citizens in times of crisis. Moreover, governments everywhere regulate behaviours that may be detrimental to individuals and society. However, there is an inconsistency on the part of government given that it derives substantial revenues from people doing many of the very activities it says are harmful – the traditional sins of drinking, gambling and drugs. What’s more, in its quest for revenues, government often advertises and promotes these same potentially self-destructive behaviours.

The conflict of interest facing governments in these situations is clear. The government is worried about the health effects of alcohol and drugs and legislates tough drunk driving laws and prosecutes drug users and traffickers. And yet, provincial governments in Canada sell alcohol at a healthy markup via monopolies. Government has made additional forays into the recreational drug market by legalizing cannabis use and setting up government sanctioned sales monopolies. Moreover, governments are quite strict in ensuring their monopolies are not eroded and will pursue legal action as seen in the Comeau Case in New Brunswick with the Supreme Court ruling to protect government’s monopoly over the interprovincial transport of beer. Meanwhile, regional vinters and breweries are promoted in glossy advertisements featuring enticing images of people drinking and socializing.

The same goes for smoking. Governments enact laws that prohibit smoking in public places and regulate the sale and advertising of tobacco products. This concern has not stopped them from raising revenue by steeply taxing the use of cigarettes and other tobacco products. While such taxes supposedly discourage smoking, the addictive nature of the product helps explain why revenues are still substantial.

Now consider gambling. Government casinos have spread throughout Canada and are used to generate revenues. Political and public consciences are assuaged by investing a portion of the revenues back into more socially responsible activities such as research into gambling addiction. Government policy is often focused on achieving fairness and equity, but studies show that lottery participation and gambling is greater among low-income groups that also spend a higher proportion of their incomes on these activities than people with higher incomes. This means revenue derived from gambling take a larger share of money out of the pockets of the most vulnerable. And given that low-income groups often already have poor health status, this higher propensity to gamble can have additional health costs associated with addiction.

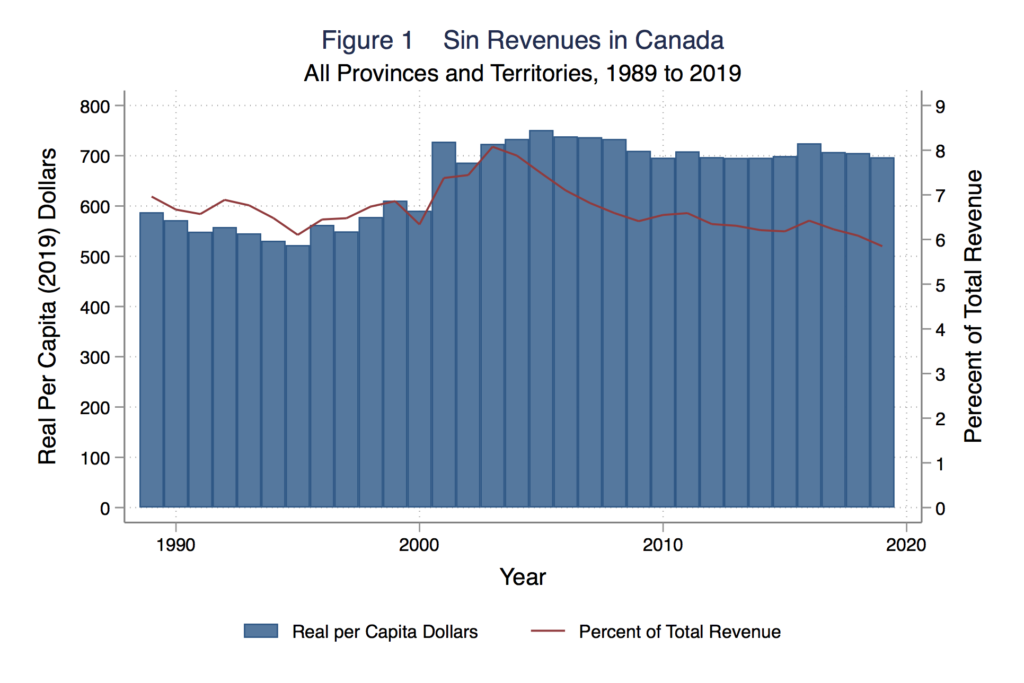

FON provides data for provincial revenues from liquor profits, alcohol and tobacco tax revenues and remitted profits on gaming and other fiscal monopolies. Taken as a whole, the long-term evolution of these revenues for the period 1989 to 2019 for all provinces taken as a whole shows growth in inflation adjusted per-capita revenues with a slight drop in the share of provincial government revenue coming from these sources. In 1989, sin taxes made up 7 per cent of provincial government revenue. In 2019, that number had fallen slightly to 6 per cent.

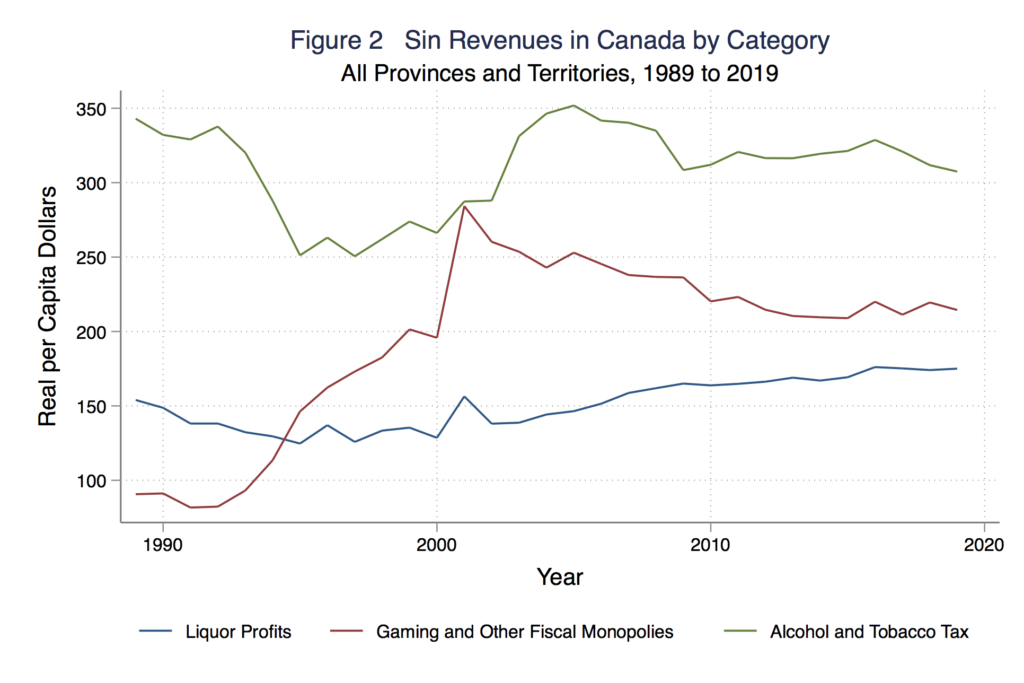

Figure 2 shows sin tax revenue collected by the provinces over time by specific category in inflation-adjusted per-capita dollars. Of the three, liquor profits have been the most stable. In contrast, gambling revenue and tobacco tax revenue seem to be more influenced by the business cycle, dropping in the wake of recessions that have occurred since the early 1990s.

The surge in gambling revenues after 2000 was driven by Ontario’s entry into casino gambling during a period of little cross-border competition. Of course, gaming profits will plunge in 2020 and 2021 given the closure of casinos during the pandemic.

Although in total sin tax revenue as a share of total revenue today is down from the early 1990s, the money still adds up. Collectively, the provinces take in billions of dollars from these sin taxes.

Canadian public policy debates have avoided grappling with this fundamental inconsistency. While luxury, vice and sin have been seen as economic drivers for centuries, given government’s public welfare mandate, should government promote and profit from activities that also cause harm? Does it make sense to promote gambling at government-run casinos and VLTs while also spending resources to reduce gambling addiction? Does it make sense for government to promote the sale of liquor and also spend health resources on the aftermath of alcohol addiction? These are tough questions. One could argue that people will always have their vices, and that such vices drive the economy. If we are going to drink, smoke and gamble anyway, why not use those activities as a revenue source? Moreover, one can argue that government provision may provide more limits on the activity and better mitigate harmful effects through regulations.

These arguments, however, do not address the conflict of interest that further exacerbates poor public health outcomes and inequalities. Public policy makers and legislators must consider how short-term fiscal benefits of sin taxes come at a steep economic and social cost of long-term addiction.. The Canadian Cancer Society estimates that smoking causes 20 percent of deaths in Canada each year and costs the health care system $6.5 billion each year. Another study by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction noted the total cost of alcohol related harm to Canadians was $14.6 billion annually. As for gambling, the Wellesley Institute estimated the annual cost of each problem gambler in terms of lost work and treatment expenses ranging from $20,000 to $56,000 annually.

So, while sin taxes may be here to stay because of the revenues that they afford government, it is problematic that those revenues go into short term consolidated revenue funds for a given fiscal year even as they leave a long-term legacy of health and social costs. It is not enough to provide token investments into addiction research. Indeed, provincial governments in Canada may want to take a page from Québec, which created its Generations Fund in 2006. This fund allows for a portion of certain tax and non-tax revenues to bypass the consolidated revenue fund and be specifically dedicated to debt reduction. In particular, revenue from alcohol taxes and natural resource revenues—as well as a share of surpluses with withdrawals—have been used to pay down the provincial debt. By 2021, the fund is expected to sit at nearly $12 billion.

The rest of Canada’s provinces would do well to imitate this practice by investing a share of revenues from liquor profits, alcohol and tobacco tax revenues and gambling profits into a sovereign wealth fund that uses the income proceeds and withdrawals from the fund to finance provincial health and social support projects and initiatives. Notwithstanding COVID-19’s fiscal impact, once the pandemic has been reined in and economies recover, provincial governments need to be more forward looking in their use of sin tax revenues.

Of course, there is the question of how much of the revenues should be invested. In the case of non-renewable resource revenues from a finite resource, the case can be made that they should all be invested in a sovereign wealth fund. As “sin tax” revenues could be considered renewable, one envisions a smaller proportion of the revenues being saved in a sovereign wealth fund for longer term use. In the absence of firmly established principles, governments could start by setting aside a 10 percent share of these revenues each year. Within five years, this would result in a fund of approximately $13 billion for all the provinces. The sooner they start, the more will accumulate.