As the Trudeau government prepares its fall fiscal update after months of record spending to address the health and economic crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent progress toward a vaccine should sufficiently mitigate uncertainty to enable a fiscal plan that shows Canadians how Ottawa will achieve its policy goals while maintaining fiscal discipline.

Mostafa Askari and Kevin Page

Former US president Ronald Reagan once said, “I am not worried about the deficit. It is big enough to take care of itself.” Should this be the basis of our federal government’s fiscal strategy in the face of the unprecedented COVID-19-related increase in the deficit? In our view, such a strategy would lead to an unsustainable fiscal situation and severely damage the federal government’s hard-earned fiscal credibility.

We argue that despite the sharp increase in spending and borrowing since the onset of the pandemic, the federal government can establish a reasonable set of fiscal anchors and rules that would allow it to fulfill important policy commitments while maintaining fiscal credibility.

The pandemic led to the Great Lockdown and the ensuing record declines in economic activity and significant job losses. Governments have responded with necessary but costly relief programs to help individuals and businesses to survive through the pandemic. The lockdown, however, has not served its public health aim of ending the pandemic. In fact, we are now seeing the second and third waves of cases and deaths in Canada and other countries. Governments will be forced to continue to impose restrictions on economic activity and provide further financial assistance to individuals and businesses.

In this context, it is imperative that the government of Canada present Canadians with a fiscal plan that shows how it will achieve its policy goals while maintaining fiscal discipline. We acknowledge that the considerable uncertainty caused by the pandemic makes fiscal planning more difficult, but it also underlines the importance of having fiscal anchors or targets that will guide its policy decisions over the next 5 to 10 years.

The federal government has argued that, in the midst of a pandemic, it is not ready to set a fiscal anchor for the medium-term planning framework. Nonetheless, the government’s fall 2020 Speech from the Throne suggests that it is considering moving forward with increased spending (for example, early learning and child care, infrastructure, and training) and revenue increases. Political parties have not outlined intentions to balance the federal budget over the medium term, likely reflecting an expectation that the global recovery could be slow and bumpy, and recognition of the need for fiscal policy to support growth after a very deep recession.

We think it is important to open the political and policy debate on appropriate budgetary constraints for the federal government in a post-COVID-19 economy.

With regard to high levels of economic uncertainty stemming from the pandemic, it is essential to lay out scenarios. Accordingly, we have examined potential medium-term fiscal outcomes based on changes in interest rates and different policy assumptions with respect to spending growth and revenue increases.

Budgetary constraints

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2015) makes the case that “[d]ebt targets can serve as a fiscal policy anchor to ensure the sustainability of fiscal policy and that there is sufficient policy room to cope with adverse shocks.”[1] After the global economic shock of the 2008 financial crisis and the resulting Great Recession, many Canadians are concerned about the potential impact of government debt built up in response to the pandemic. After the Canadian government returned to a balanced budget in 2015, a second shock in 12 years will add many hundreds of billions in government debt and some 20 percentage points to the ratio of federal debt to gross domestic product (GDP).

The need for budgetary constraints on government is largely grounded in common sense. Governments, unlike private citizens, are not spending their own money. It is generally not politically popular to raise taxes. As a result, there is a natural bias toward deficits. Formal budgetary constraints play an important policy role. With due regard to fiscal discipline, they send important signals to citizens and financial markets about the role that fiscal policy will play in supporting economic growth and maintaining fiscal sustainability.[2] Budgetary constraints can help to frame difficult political conversations on priorities and policy tradeoffs. They also serve as an important accountability tool by increasing the political costs of running high deficits.

In periods of crisis, governments are expected to respond to protect people, businesses, and country. Lessons have been learned, from the Great Depression in the 1930s to the global financial crisis in 2008 and during periods of war. Governments must act quickly and employ all available fiscal and regulatory tools. The time to restore fiscal health takes place after the crisis.

Governments around the world are rethinking appropriate budgetary constraints in a post-COVID-19 environment. Prior to the pandemic, the federal government commitment was a declining debt-to-GDP ratio. With Canada’s relatively low net debt-to-GDP ratio when compared to other countries and a high investment-grade bond rating, a fiscal rule defined by a declining ratio was both simple and flexible.

Members of the European Union (generally, countries with higher debt-to-GDP-ratios than Canada and lower bond-rating grades) had a more complex set of budgetary constraints involving debt, budgetary balances, spending, and escape clauses. To minimize procyclical policy responses that could destabilize the economy, targets and rules were calculated on a cyclically adjusted basis, adding to the complexity. Conversations about a new generation of budgetary constraints had already started prior to the pandemic.[3]

OECD (2015) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2018) policy advice on an appropriate budgetary constraint involves a handful of essential tools.

- Fiscal anchor. This refers to a prudent, country-specific debt target. The target should be set well below a debt threshold where general opinion believes higher debt will negatively impact the economy (reduce confidence and investment and/or increase the risk of a bond-rating adjustment). It is usually expressed as a percentage of GDP over a medium-term horizon.

- Fiscal rules. These are annual targets for budgetary balance and/or spending. These targets are set to increase the chances that the debt target will be achieved. In essence, they represent an operational rule. They are set with regard to economic growth and stabilization and fiscal discipline.

- Escape clauses. These allow governments to reset fiscal policy, fiscal anchors, and fiscal rules as a result of an adverse shock to the economy (such as a pandemic or a global financial crisis).

- Enforcement. This is the use of independent fiscal institutions such as Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) to ensure reasonable prospects of the government achieving its target and/or to advance policy guidance on how the government will respond if targets are missed.

The advice from international institutions suggests a more comprehensive approach to fiscal discipline than the government’s pre-COVID-19 declining debt-to-GDP ratio fiscal rule. There are a number of post-COVID-19 scenarios that could help to identify a reasonable set of budgetary constraints for the federal government.

A baseline scenario

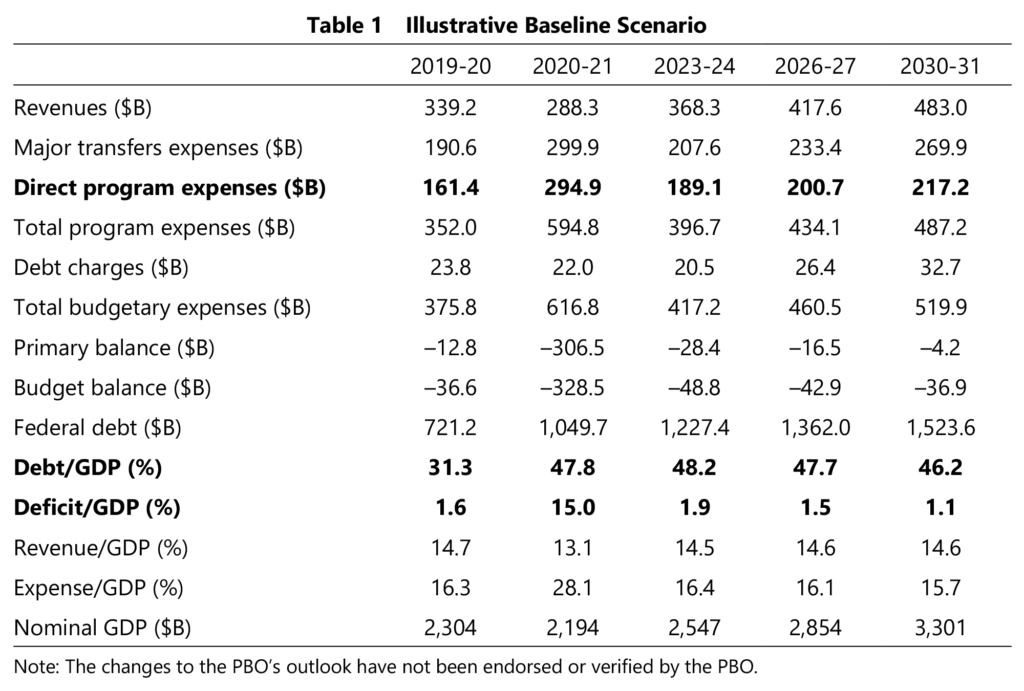

Since the Economic and Fiscal Update of November 2019, the federal government has not provided a medium-term economic and fiscal outlook. In July 2020, Finance Canada presented the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot, which contained a fiscal outlook only for the current fiscal year. In September, the PBO released its five-year economic and fiscal projection. The PBO’s projection assumes that the need for pandemic-related public health measures will gradually decline over the next 18 months as a vaccine becomes available. As an illustrative baseline scenario, shown in table 1, we have extended the PBO’s outlook for another five years and made some adjustments to the initial five-year projection as follows:

- Nominal GDP is assumed to grow at 3.7% a year from 2026-27 to 2030-31.

- Government revenues and major transfers to persons and other levels of government are assumed to grow with GDP from 2026-27 to 2030-31.

- Direct program expenses (DPE), the most discretionary part of government spending, are assumed to grow at 2% a year from 2023-24 to 2030-31.

- The effective interest rate is set at 2.2% from 2026-27 onward.

In the baseline scenario, there is a moderate increase in government spending over the medium term. It shows moderate deficits after this, declining to just over 1% in 2030-31. It also shows that the debt-to-GDP ratio stays on a slowly declining path starting in 2023-24, reaching 46% by the end of the forecast period. This portrays a relatively disciplined fiscal framework, but there is not any fiscal space for the government’s initiatives announced in the Speech from the Throne.

Alternative scenarios

We will examine several alternative scenarios to assess the impact of a higher effective interest rate, different profiles for DPE, and higher tax revenues.

Higher interest rates. An effective interest rate that is 50 basis points higher on average over the medium term would raise the debt-to-GDP ratio from 46.2% to 48.5% and the deficit-to-GDP ratio from 1.1% to 1.7% in 2030-31. Moreover, the debt-to-GDP ratio would no longer be on a downward path; it stays relatively stable over the period. If interest rates rose further, the debt-to-GDP ratio would be on a rising path.

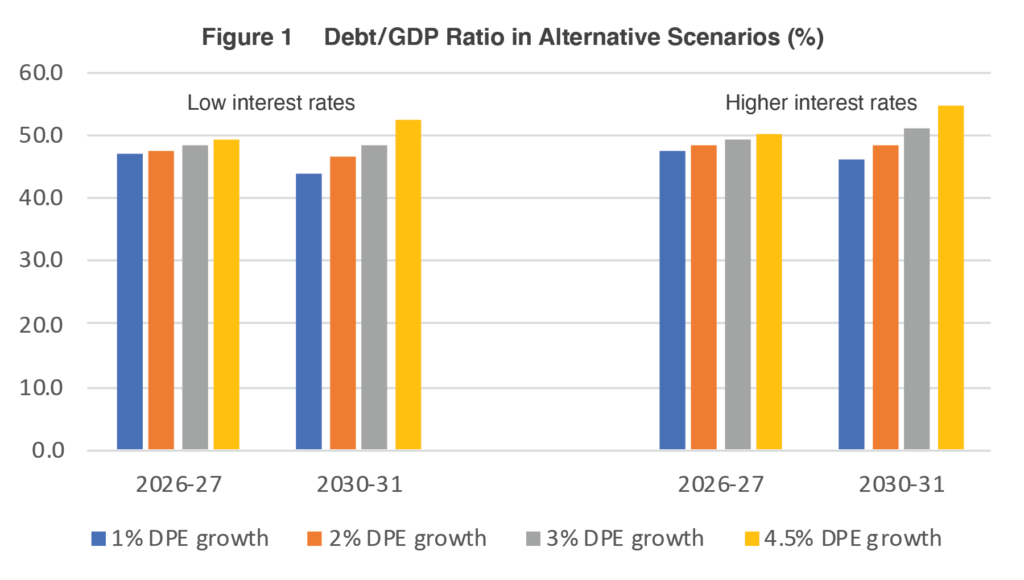

Alternative spending profiles. We consider three alternative spending scenarios to show how the potential fiscal anchors and targets such as the debt-to-GDP ratio, the deficit-to-GDP ratio, and the spending-to-GDP ratio are affected. We examine one austerity scenario where direct program spending is increased by only 1% a year to achieve lower deficit and debt profiles, and two scenarios where direct program spending is increased by 3% and 4.5% to create enough fiscal space for the government to fulfill some of its policy commitments. Figures 1 to 3 depict the impacts of these scenarios with low and higher interest rates.

These scenarios show that if direct program spending were to increase by only 1% a year, the fiscal situation would improve over time with lower debt-to-GDP ratio, deficit-to-GDP ratio, and spending-to-GDP ratio. Spending growth above the baseline scenario (that is, 3% and 4.5% growth) would lead to higher levels for all of these indicators, even if interest rates remained low throughout the period. For example, if direct program spending increases by 4.5% a year, the debt-to-GDP ratio would reach 55% by the end of the period.[4]

The latter two scenarios, however, would provide ample fiscal space for the government to fund its policy priorities and help the economy to recover faster. Figure 4 depicts the extra fiscal space relative to the baseline for the higher spending scenarios. In other words, it shows the amount of additional money that the government would be able to spend on its various priorities beyond what would be possible under the baseline scenario. By 2030-31, there will be extra fiscal space of $17 billion and $46 billion respectively in the 3% and 4.5% scenarios.

Alternative revenue profiles. Given the significant deterioration in the government’s fiscal situation, the federal government may consider tax increases to partially offset the rise in the deficit. To illustrate the impact of tax increases, we examine two scenarios where, through tax rate changes, the government raises the level of revenues in 2023-24 by 3% and 5%. As a result, the revenues would rise by $14 billion and $24 billion respectively by 2030-31.

Figure 5 shows that the rise in revenues would significantly reduce the debt-to-GDP and deficit-to-GDP ratios.

The spending and revenue scenarios examined show that the government can choose as a fiscal anchor the debt-to-GDP ratio and set it between 45% and 55%. This would be consistent with growth targets for direct program spending of between 1% and 4.5%.

A recovery scenario. In its October 2020 Fiscal Monitor,[5] the IMF suggests that significant public investment is needed in advanced economies to boost employment and economic growth and to crowd in private investment. Given the expectation that interest rates will remain low for a long period, even in our higher interest rate scenario, such investment can be accomplished without raising the interest costs of more borrowing. Policy makers must consider the tradeoff between a faster and more robust recovery and higher deficit and debt. There may also be a need for new sources of revenue to mitigate the impact on government finances.

We examine a scenario, shown in table 2, where the government follows the IMF’s advice and front-end loads more spending to help the recovery, followed by a targeted slowdown in the rate of growth of government spending. We assume that direct program spending will be raised by $20 billion a year from 2023-24 to 2026-27 relative to the baseline scenario, with half of the spending allocated to infrastructure investment. Assuming that by 2026-27 the economy is fully recovered from the impacts of COVID-19, the rate of growth of direct program spending is reduced to a targeted 1% a year for the rest of the period. We also assume that tax increases will raise the level of revenues by 5% in 2023-24. Thereafter, revenues are assumed to grow as in the baseline scenario.

The front-end loading of spending and the establishment of a low spending-growth target for the rest of the period would reduce the level of spending by about $34 billion by 2030-31 relative to the scenario where direct program spending increased by 4.5%. This will help reduce all the key fiscal indicators as shown in table 2. The debt-to-GDP ratio stays relatively stable at about 48% and the deficit-to-GDP ratio declines steadily, reaching 1.3% by 2030-31.

In short, the recovery scenario shows that if the government is able to slow down spending in the outyears, it can choose significant spending increases relative to the baseline scenario in the earlier years to help encourage economic recovery while achieving approximately the same debt-to-GDP ratio.

It is important to note that the scenarios presented here do not take into account the negative impacts of tax increases and the positive impacts of spending increases on economic growth. The tax increases are likely to have a small negative impact on growth. On the spending side, however, the IMF suggests that in the current environment of considerable uncertainty and excess capacity, infrastructure investment could have a multiplier effect as high as 2.7, which means that every dollar of infrastructure spending could raise GDP by as much as 2.7 dollars.

Considerations on budgetary constraints in a post-COVID-19 economy

Different policy scenarios allow political parties to reflect on tradeoffs between policy priorities and the need for fiscal responsibility. Higher debt can be used to strengthen the recovery and address fundamental issues related to climate change and growing income disparity, but it can also reduce fiscal room to address future adverse shocks (such as another pandemic).

Extending the medium-term horizon from 5 to 10 years can allow policy makers to examine policy strategy that will need to evolve—the need for fiscal stimulus to address a weak economy over the next few years, and the need for restraint when the economy returns to its potential. This approach would help to ensure that fiscal policy takes on a countercyclical (stabilizing) stance with a commitment to a medium-term debt target or fiscal anchor.

In setting an appropriate debt target for the medium term, policy makers would need to consider the debt threshold for Canada and the cost of policy initiatives they think are essential for Canada’s future. For Canada, a debt threshold could be an estimate of debt they think would entice bond-rating agencies to reconsider our triple-A bond rating (the highest investment grade). At the current time, Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s bond-rating agencies rate Canada at AAA with a stable outlook. This is largely consistent with Canada’s relatively low net debt-to-GDP ratio compared to other advanced economies. By contrast, the Fitch bond-rating agency lowered Canada’s rating in 2020, reflecting the relatively large increase in debt in 2020 and uncertainty about fiscal policy going forward.

In this environment, Canada should strengthen the pre-pandemic fiscal rule of a declining debt-to-GDP ratio in line with advice from international institutions. And, in keeping with IMF (2018) advice, the new budgetary constraints for Canada should be “simple, flexible and enforceable.”

In keeping with OECD (2015) advice, the new planning framework should be expanded to include a fiscal anchor (debt target), fiscal rule (spending growth constraints consistent with the fiscal anchor), an escape clause (providing that fiscal policy should change if planning assumptions are substantially incorrect), and added enforceability mechanisms (improved oversight).

In the context of the scenarios above, we would like to see an open political and public policy discussion on the following:

- fiscal anchor: medium-term federal debt-to-GDP ratios could be set in the 46% to 50% range;

- fiscal rule: discretionary spending targets could be expressed in annual growth rates in the 2% to 4% range, depending on possible initiatives to increase revenues and economic assumptions; spending growth commitments would be tied to policy priorities including the need to strengthen the economic recovery;

- escape clause: deviations in projected real GDP in excess of 2 percentage points should trigger a policy response by the federal government; and

- enforceability: the PBO, like independent fiscal institutions in the EU, should be given a formal role in assessing the likelihood that the federal government is on track to achieve its fiscal anchor.

Canada and the world face enormous uncertainty because of the unpredictability of the pandemic and vaccine timeline. Eschewing the discussion of a long-term fiscal plan with budgetary constraints will only add to, rather than lessen, that uncertainty.

This commentary is a modified version of an article originally published in Policy Magazine.

[1] F. Fall et al., “Prudent Debt Targets and Fiscal Frameworks,” OECD Economic Policy Paper no. 15 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrxtjmmt9f7-en.

[2] X. Debrun and M.S. Kumar, “Fiscal Rules, Fiscal Councils and All That: Commitment Devices, Signaling Tools or Smokescreens?” in Fiscal Policy: Current Issues and Challenges, papers presented at the Banca d’Italia Workshops on Public Finance, Perugia, 29-31 March 2007 (Rome: Bank of Italy, 2008), 479-512, https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/altri-atti-convegni/2007-fiscal-policy/Debrun_Kumar.pdf.

[3] L. Eyraud, X. Debrun, A. Hodge, V. Lledó, and C. Pattillo, Second-Generation Fiscal Rules: Balancing Simplicity, Flexibility, and Enforceability, IMF Staff Discussion Note, April 2018, SDN/18/04.

[4] These scenarios do not consider the potential positive impact of higher spending on the level of GDP, which would mitigate the rise in debt and deficit.

[5] International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Monitor: Policies for the Recovery (Washington, DC: IMF, October 2020), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/09/30/october-2020-fiscal-monitor.