By: Julie S. Gosselin, Luc Godbout, Tommy Gagné-Dubé, Suzie St-Cerny

Chaire en fiscalité et en finances publiques

Université de Sherbrooke

This post summarizes the article recently prepared for Finances of the Nation by Gosselin et al. on economic responses to the Covid-19 pandemic crisis by governments in Canada.

The COVID-19 pandemic, first a major health emergency, quickly turned into an unprecedented economic crisis caused by government-imposed containment measures to curb the spread of the virus. It prompted states to intervene as never before since World War II. Our analysis seeks to recount how Canadian governments have responded to the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis through the economic measures announced from the beginning of the crisis to mid-May 2020.

Canada’s early economic response to the crisis unfolded in two parts. Initially, the priority was to deal with the health emergency and to rapidly cushion its impacts on households and businesses facing liquidity pressures and revenue losses. The first cash flow support measures increased credit availability for businesses, but in this emergency phase, the most significant liquidity support took the form of broad-based personal and corporate tax easing measures. In the provinces, early direct support measures targeted sick workers or those obligated to self-isolate who did not qualify for EI benefits, a support meant to bridge the period until the Federal Government announced its own program. This federal announcement was first made on March 18, with two new emergency allowances for workers forced to stay home and non-EI-eligible workers facing unemployment. Other measures put in place at the beginning of the crisis targeted vulnerable people (notably through lump sum enhancements of existing transfers to individuals and families) and industries.

On March 25th, the Federal Government’s unveiling of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) marked the beginning of a second phase of governments’ interventions: the response to the shutdown of the economy. Since then, Canada’s economic response was built around two measures designed to support workers’ income: the CERB, for those who had lost their jobs, and the CEWS, a 75% wage subsidy to help businesses suffering from revenue losses keep their employees on the payroll. From this point, most announcements expanded the duration or the scope of existing measures to prevent containment from causing too much damage to the labour market and the economy’s production capacity. Emergency loans, grant programs and additional easing measures were implemented. Some support measures targeted specific economic sectors, such as the agri-food industry, the energy sector, tourism and the cultural sector.

This analysis shows that Canadian governments have acted quite rapidly and that, by expanding emergency measures, they have tried to help just about everyone. Overall, Canada’s economic response is consistent with the trends observed in most OECD countries. As of May 6th, 34 of the 37 OECD member countries had implemented some form of support intended for employees or self-employed workers facing income losses, however, the CERB, a made-in-Canada response to the crisis, is almost unique. Many countries achieved a similar result by changing the existing rules of their unemployment insurance system. Wage subsidies for businesses were implemented in nearly two thirds of OECD countries.

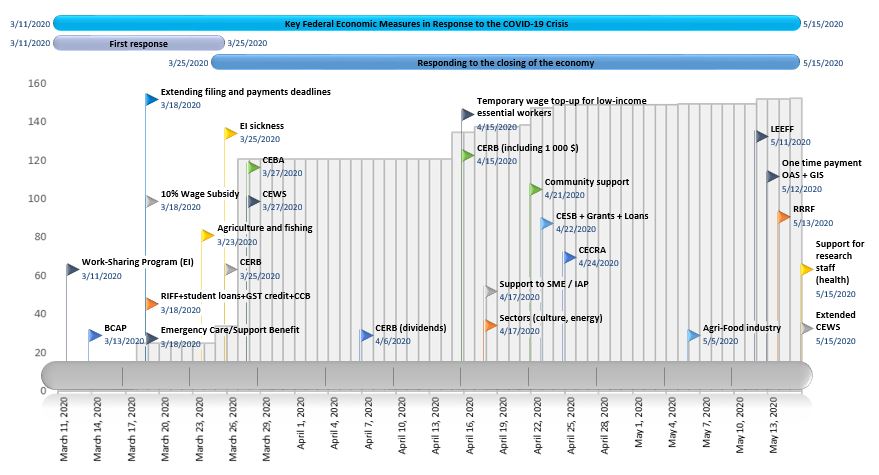

As of May 15, 2020, the Government of Canada had announced more than $150 billion in direct assistance measures for businesses and households. Figure 1 displays numerous federal announcements made since March 11th. In the background, a graph shows the cumulative day-to-day costs of programs. The largest jumps on the curve reflect the cost of the CERB announcement on March 25th, part of which was announced on March 18th with the two emergency benefits, as well as the CEWS announcement on March 27th.

Figure 1: Timeline and cumulative costs (B$) of key federal economic measures

The information available on the costs remains fragmented and these will have to be better documented at the time of the final assessment, but the importance of the aid is undeniable. Additional spending will also be needed for economic recovery, and to prepare for a possible second wave of the virus.

On May 15th, as Bill Morneau announced the extension of the CEWS, he indicated that all upcoming adjustments would aim to “Promote jobs, promote growth.” Future actions must send a clear message about the need to gradually return to a more “normal” pace, with everyone’s participation. The support measures that inevitably remain in place will need to be better targeted. As of today, both the CERB and CEWS have been extended, but without any real revisions of their parameters.

In terms of costs, the most significant measures targeted workers and companies most affected by the crisis. However, the speed of implementation, especially in the case of the CERB and the closely related CESB, may have opened the door to some abuse.

With the cost of the two flagship programs (CERB and CEWS) estimated at $125 billion as of June 26th, governments will inevitably evaluate the actions taken to respond to the emergency in order to identify what went well and what did not. They will also have to carry out audits to make sure the money went where it was supposed to go.

While a critical discussion of the choices that were made and their implementation process is essential in any democratic society, the urgency and the uncertainty that prevailed when decisions were made should not be forgotten. The speed of action in this emergency state undoubtedly helped to reassure people, to demonstrate the presence of governments. Learning from this unprecedented situation will be critical to improve the resilience of the fiscal system and to ensure we do better next time. Without being exhaustive, a few elements are already clear:

- The shortcomings of Canada’s employment insurance program have forced the creation of the CERB, a parallel program. Due to the weakness of its underlying technology and administrative system, the EI program was unable to handle the explosion of new claims and the necessity to extend eligibility criteria to non-standard workers.

- The CERB was rapidly implemented with simple parameters, but it has had obvious effects on work incentives.

- In the context of the Canadian federation, the pandemic required both levels of government to develop new public policies. Most governments’ interventions were complementary, although some contradictions appeared. For example, Quebec introduced an early agricultural financial support program to attract students, among others, to fill the shortage of foreign workers. The program’s appeal was greatly diminished by the creation of Canada’s Emergency Student Benefit.

- Once the CERB and CEWS were implemented in April, the federal government expressed its willingness to switch CERB recipients to the CEWS. Accordingly, the initial cost of the CEWS was estimated at $76 billion, exceeding the first evaluation of the CERB’s cost by more than $50 billion. However, the CERB has been consistently more popular than the wage subsidy, and its estimate cost has now reached $80 billion while the CEWS’ cost for the first 12-week period was revised to $45 billion. The government’s intent that employers use the wage subsidy to rehire a large number of laid-off employees has not materialized. While the order of the implementation of the two programs is certainly not unrelated to the situation, the reasons for the CEWS’ relative unpopularity, despite its greater generosity, will need to be clarified.

These few examples alone illustrate the need for a critical post-crisis analysis of governments’ responses.