Ayaka Behro, Michael Smart, and Trevor Tombe

The ongoing recovery from COVID has been stronger than many suspected and many emergency support programs have ended. Using the latest federal Fiscal Monitor data, we explore revenue and expense trends. We present a simple forecasting model to project revenue, expense and the federal deficit to the end of the fiscal year.

Typically, mid-year fiscal updates, like the one unveiled Tuesday by Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, adjust budget numbers — including revenues, program expenses, the overall deficit, and more — slightly up or slightly down. This year, there’s some good news. Economic growth has improved, and so too has the budget situation of many provinces. In this post, we’ll explore Canada’s fiscal situation using the latest federal data and forecast where we might be headed by the end of the fiscal year next March.

Given how economic and fiscal circumstances having been changing from one month to the next during COVID, it is difficult for Canadians to understand the state of their government’s finances. Comprehensive fiscal information comes only with a long lag. We still (as of this writing) do not have comprehensive Public Accounts data for the federal government’s fiscal year 2020-21, let alone for the current fiscal year.

But the federal Department of Finance publishes a monthly “Fiscal Monitor” – containing a wealth of information on its revenues and expenses – with only a two-month lag. Finances of the Nation has digitized the monthly Fiscal Monitor data back to the 2000-01 fiscal year and will update it continuously going forward. This new Fiscal Monitor dataset is now publicly available through our website, together with visualization tools allowing users to explore the details of federal finances and to compare across years.

In addition to revealing where we are and have been, the data can be useful to forecast where we’re going.

The current state of federal finances

Currently, the latest information we have is up to September 2021. On Friday, we’ll receive and incorporate an update to include October. But with the first half of the fiscal year now available, there’s much we can learn. The Fiscal Monitor data tell a clear story: as shown in Table 1, revenues have recovered to higher levels than before the pandemic and, while expenses remain high, the federal deficit is substantially less than last year.

Table 1: Federal fiscal balances to September, current and prior fiscal year

| April to September of Fiscal Year | Per cent | ||

| 2020/21 | 2021-22 | Change | |

| Revenues | 128,848 | 175,817 | +37 |

| Program Expenses | 316,568 | 232,693 | -27 |

| Public Debt Charges | 10,390 | 11,692 | 13 |

| Budget Balance (Deficit/Surplus) | -198,110 | -68,568 | -65 |

What’s behind the improvement?

Federal expenses

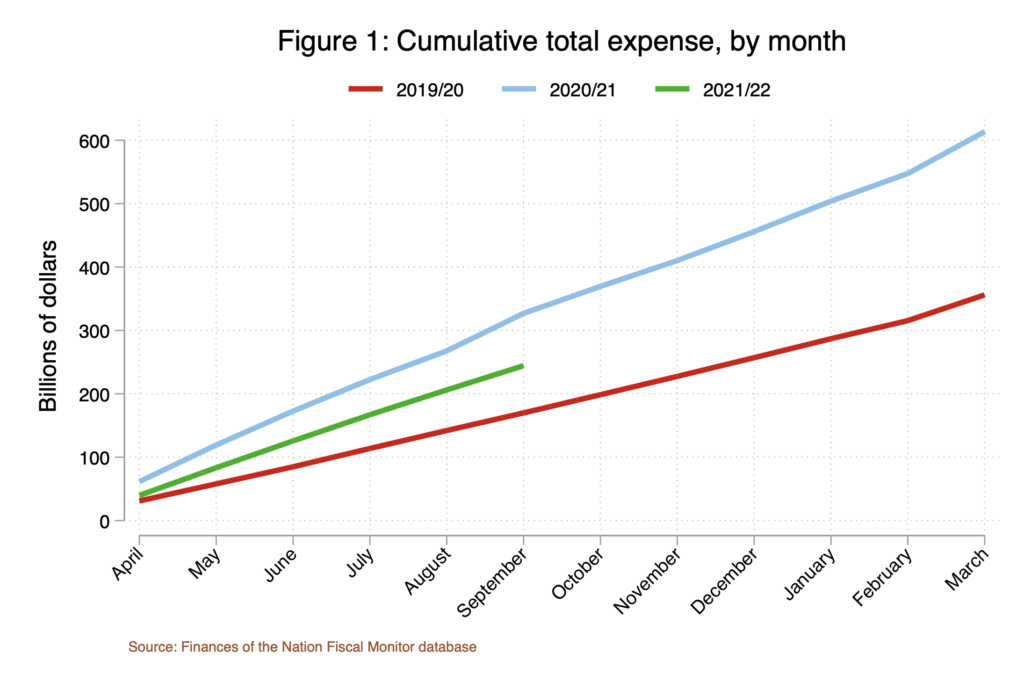

As of September, program expenses were down more than 27 per cent compared to the same time last year. They also appear to also be trending downward in recent months. Figure 1 shows the cumulative total expenses for each month since the beginning of the fiscal year. Outlays have been clearly trending steadily downward. This mainly reflects lower transfers to persons including EI and Canada Recovery benefits – reflecting the decline in unemployment and the expiry of benefits. CEWS payments are also running $3 billion less per month than last fiscal year, although the extension of the program and CHRP will likely keep this component steady for the rest of the year. Overall, the government’s spending trajectory is halfway between its pre-COVID trajectory and the high spending year of 2020/21.

Federal revenues

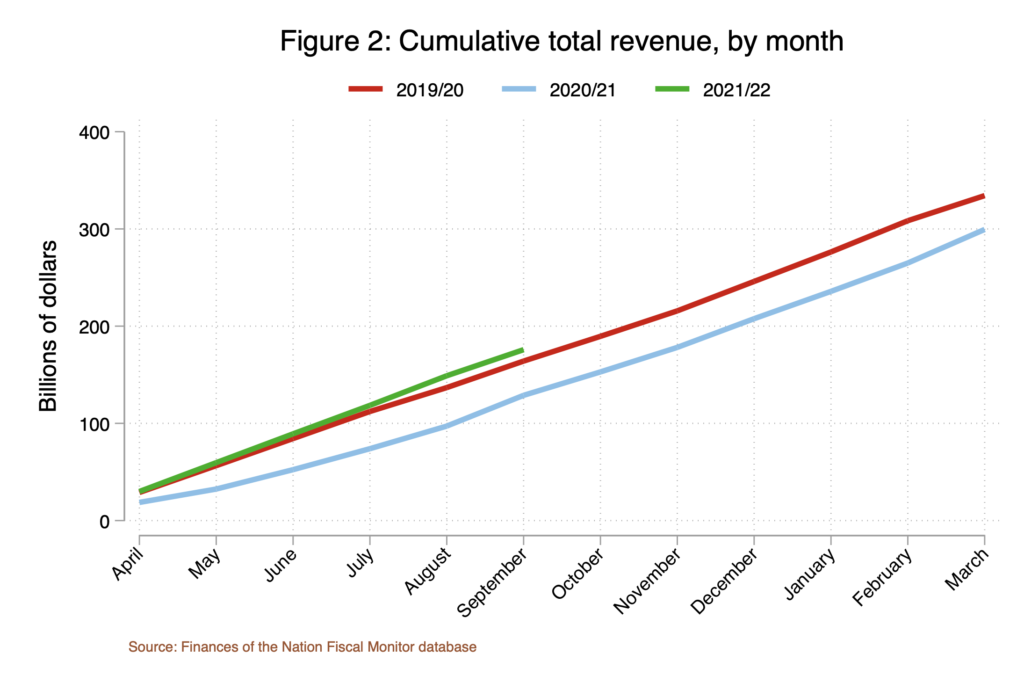

Buoyed by a recovering economy (and eliminating deferrals implemented early in the pandemic), revenues are also up from last year. As of September, revenues are more than one-third higher than the same time in 2020-21. Figure 2 shows the cumulative total revenues since the beginning of the fiscal year. Overall, revenues appear strong – fully recovered from the pandemic and higher than they have ever been in nominal terms. That said, revenues were down substantially in the month of September, relative to August and to the growth seen in prior years, reflecting declines in both goods and services and personal income tax revenues. This is despite the sharp rise in consumer prices in July and August, which some have suggested is causing an of an “inflation bump” to revenues.

So, where might we be headed in the second half of the fiscal year? We’ll hear the Finance Minister’s projections tomorrow. But given the uncertainty we face today, having multiple projections may be valuable. So, for the first time, Finances of the Nation offers one.

A nowcasting model of federal finances

The Fiscal Monitor data contain timely information about current trends in economic conditions and how they impact federal finances. As these trends evolve over the months of the year, they can be projected to predict where we’re headed by the end of the fiscal year. The preliminary forecasting model we describe here is a simple one, and it is not a substitute for the large structured economic models employed by the Department of Finance and other economic forecasters. But our approach is simple and transparent, it incorporates the latest information released in the Fiscal Monitor, and past experience suggests it is reasonably accurate. So its results are (at the very least) informative and worth considering.

How does it work? We use the historical fiscal monitor monthly data for the 2000 to 2019 period, applying regression methods to predict the year-end totals in the Fiscal Monitor at each monthly horizon through the current fiscal year. In our model, the prediction for the year-end total for revenue and expense at each forecast horizon is the sum of monthly data already observed, plus the best unbiased predictor of the remaining months, estimated as a linear function of the most recent months of data, and of the corresponding total of early months in the prior fiscal year.

Aside: The model is estimated recursively, with coefficients estimated using data from 2000-01 up to the end of the prior fiscal year, and an out-of-sample prediction is formed for the following fiscal year. The number of lags included in the regression were chosen to minimize mean one-step ahead forecast error. Among estimators with similar mean forecast error, we chose the lag with minimal mean square forecast error. For revenue, we use one lag of monthly revenue to predict the future. There is more persistent to shocks to monthly expense, and we use four monthly lags to predict expense.

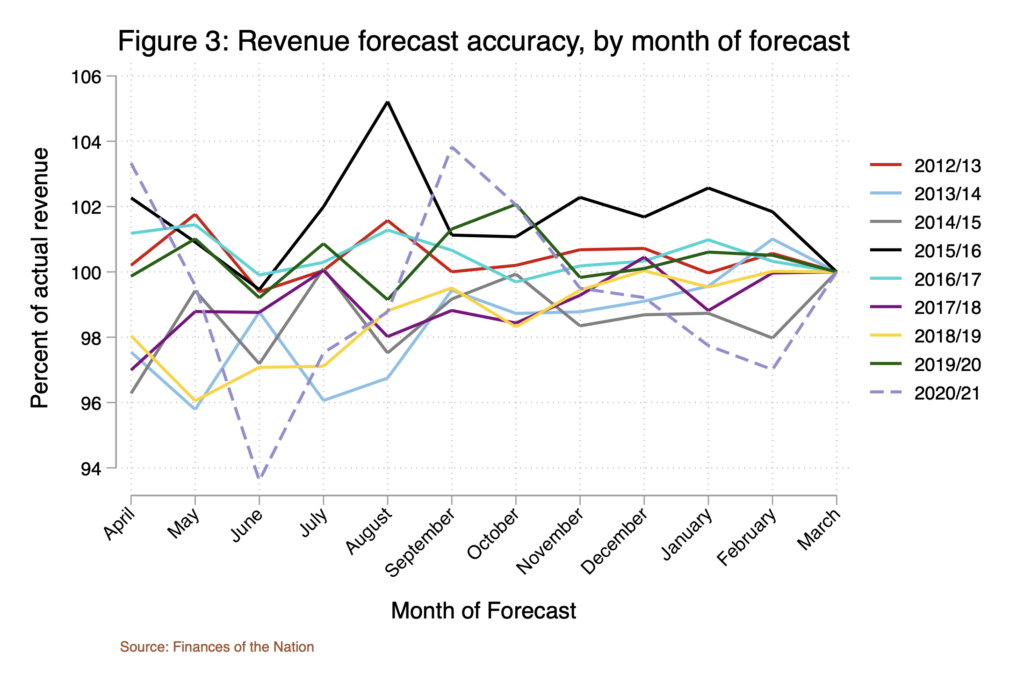

How can we be confident the model does a good job? We dial back the fiscal clock and ask what the model would have predicted about past budget values if we only had data up to a certain month within the first year. If the model consistently gets within a couple percentage points of the actual results for that fiscal year, that’s a good sign.

Our model indeed performed well. We simulated hypothetical predictions of revenue, for example, from every fiscal year from 2012 to 2020 (yes, that 2020). Figure 3 shows the resulting forecasts for year-end totals, presuming we had data only up to each month of the fiscal year as indicated by the horizontal axis. As expected, errors are large at the beginning of the fiscal year, but they decline to zero as the year proceeds. After six months (April to September data), forecast errors were between -1.2 per cent and +1.5 per cent in the 2012-13 to 2019-20 period. Not surprisingly, the error for the COVID year 2020-21 was larger, at +3.8 per cent — but still not bad. (Forecast errors for expenses were similar up to 2019-20, but after six months of 2020-21, our model would have underpredicted spending by 7.2 per cent.)

The near-term future for federal finances

As noted, federal finances in Canada are improving. Revenue has been consistently strong through the year, with a slight dip in September, and expense has been trending steadily downward.

Our model predicts that the year-end totals for revenue will be $58.9 billion higher and expenses $158.3 billion lower than in 2020-21.

Table 2: Comparing our forecast to the 2021 budget

| Forecast Change from Prior Year ($ Billion) | ||

| Item | 2021 budget | Finances of the Nation |

| Revenue | +58.9 | 58.9 |

| Expense | -140.5 | -158.3 |

| Budget Balance | +199.4 | +217.2 |

Broadly speaking, our forecast is close to the 2021 budget 2021, which anticipated a $58.9-billion increase in revenue and $158.3-billion decrease in expense. Our forecast for revenue gains are identical but our forecast for expense declines are larger. We forecast that the deficit will fall by more than $217 billion to $137 billion, a smaller deficit than in predicted in the 2021 budget 2021.

A few caveats are in order. This data does not correspond exactly to the totals reported in the Public Accounts. The monthly Fiscal Monitor data is prepared on a modified cash basis. The Public Accounts make adjustments based on information received after the end of the year, to put the data onto an accrual basis. Such adjustments are usually small — “a few billion” — but in the current environment, they could be large. In 2019-20, for example, the first tranche of COVID-related programs drove spending higher late in the fiscal year, resulting in a $17.5-billion discrepancy between Fiscal Monitor and Public Accounts. As well, this forecast also does not incorporate new measures announced but not yet fully phased in. For example, the latest extension of CEWS and other benefit programs is forecast to add $7.4 billion to the deficit this year. The planned increase to OAS benefits could add still more.

Conclusion

Following a shock as large as COVID was, there is inevitably much economic and fiscal dust left to settle. The projections for federal finances that we’ll see tomorrow will be incredibly valuable. But in between such updates, the monthly Fiscal Monitor data — now available in an accessible format through Finances of the Nation — will add much to our understanding of where we are and where we’re going. The projection we presented here but it illuminates the scale of improvement in federal finances relative to 2020-21. But as we have not yet fully recovered from COVID or normalized our government finances, where we go from here will be important to watch. Near real-time data, and projections based on it, will be an important tool to shape our understanding of Canadian public finances.

Finances of the Nation will be here to share the data, and that insight, whatever might come next.

Image Credit: Adam Scotti (PMO), Official Photo