Ben Eisen

For the past 35 years, debt aversion has been an organizing principle of Canada’s federal fiscal policy. This commentary demonstrates the fact of fiscal policy continuity focused on debt aversion since the 1980s and asks whether the current surge in debt is simply an emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession or the beginning of a new era of fiscal policy that is markedly less focused on avoiding debt.

Introduction

Since the Mulroney government in the mid-1980s, debt aversion has been a consistent feature of Canadian federal fiscal policy. There have been differences in various governments’ priorities and choices of fiscal anchors. Nevertheless, on whole, the federal government’s approach towards debt accumulation has been generally characterized by policy continuity rather than change in recent decades.

More specifically, successive governments have sought to avoid or run small deficits except in the immediate wake of recessions. When recessions have hit and large deficits emerged, governments have (until very recently) consistently provided forward guidance with target dates for a return to balance. As a corollary, federal fiscal policy has relied on spending restraint to achieve the objective of limiting debt accumulation.

Given the public appetite for additional social spending, governments in democratic countries often find it difficult to maintain spending restraint and avoid debt accumulation over time. The longevity of Canada’s policy approach of spending restraint and debt aversion is therefore remarkable. Recent developments, however, suggest that debt aversion’s lengthy run as an organizing principle of federal fiscal policy may be coming to an end.

This commentary seeks to demonstrate the extent to which debt aversion has been an important feature of federal fiscal policy since the mid-1980s and concludes by discussing recent developments that may herald the end of this fiscal policy era.

Canada’s Era of Debt-Aversion

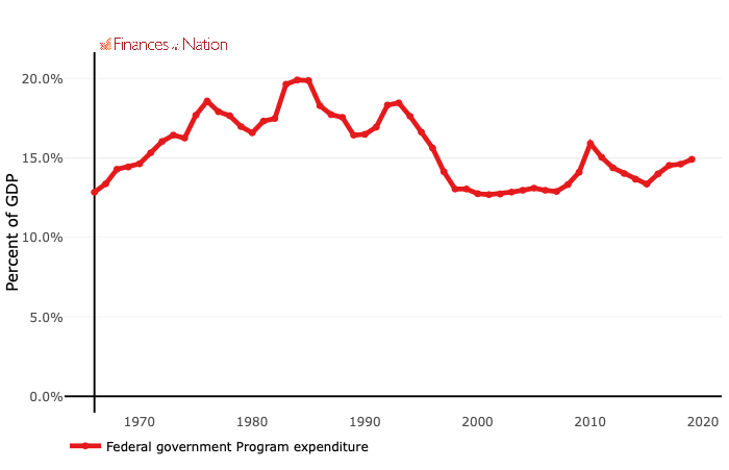

Let’s begin by examining how program spending has evolved over the past 35 years. Figure 1 shows program spending as a share of GDP since 1967.

Figure 1 Program Spending/GDP

Although the 1995 budget is often identified as the starting point of Canada’s late 20th century fiscal consolidation, the process actually began in the mid- 1980s. Program spending fell from 19.9 per cent of GDP in 1985 to a low of 12.7 per cent in 2001. Since then, there has been mild growth, with spending relative to GDP remaining well below the 1985 peak.[1]

Initially, the objective of this spending restraint was to reduce and eventually eliminate the federal deficit. As figure 2 shows, in 1985, the federal deficit stood at 7.8 per cent of GDP. By the time of the 1995 budget, this had been cut nearly in half to 4.6 per cent. In fact, while the 1995 budget tabled by the Chretien government is correctly viewed as a historically important moment in the history of federal fiscal policy, the spending restraint already initiated by the Mulroney government had already all but eliminated the federal deficit, except for interest payments on the debt.

The federal government finally reached a balanced budget in 1998. In the following decade under several prime ministers, the federal government maintained balanced budgets while using extra available fiscal room to either reduce various taxes or explicitly reduce federal debt.

Figure 2 Fiscal Balance as a Share of GDP

A deficit did emerge in the wake of the 2008/09 financial crisis. The Harper government explicitly made a rapid return to balance a primary policy objective and kept spending growth low to pursue this goal. Specifically, the Harper government significantly reduced real per-person spending from 2010 to 2016 in a successful effort to shrink the deficit. By 2016, the deficit had been reduced to almost nothing.

Despite a sharp difference in political rhetoric, the Trudeau government (pre-pandemic) shared the Harper government’s policy of keeping deficits small, as they did not exceed one per cent of GDP between 2015 and 2019.

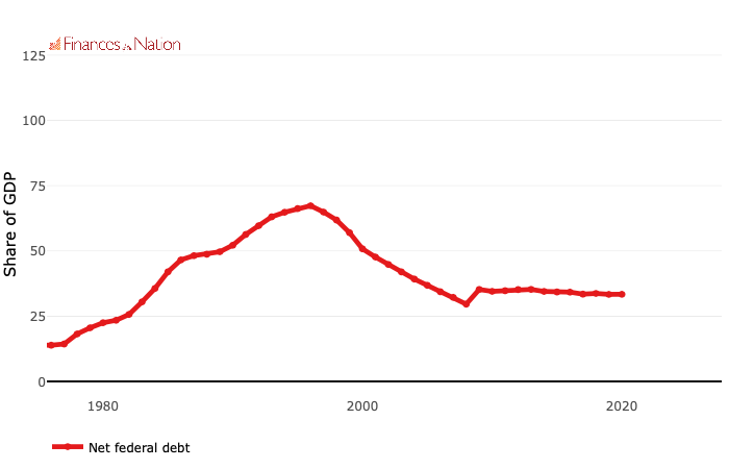

The result of the spending restraint described above, and the avoidance of large deficits by successive federal governments, coupled with a favourable interest rate environment has been a substantial reduction in Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio. Figure 3 shows that net debt peaked at 67 per cent of GDP in 1996 and fell to 29.6 per cent in 2008. This ratio remained virtually unchanged until the COVID-19 recession.

Figure 3 Federal Debt to GDP Ratio

The Times, Are They A-Changin’?

Debt aversion’s long-standing place at the centre of federal fiscal policy may be coming to an end. In the years immediately prior to the pandemic the Trudeau government was already taking small steps in a new direction. Specifically, the government increased spending as a share of GDP during a period of mild economic growth. Relatedly, it prioritized the creation of a substantial new welfare state program, the Canada Child Benefit, over tax reductions.

Furthermore, the Trudeau government explicitly abandoned the long-standing balanced budget fiscal anchor/target at least in the short term, replacing it with a less restrictive anchor of avoiding growth in the federal government’s debt-to-GDP ratio. This change was reflected by the publication of federal budgets that did not contain forward planning showing a path towards a balanced budget.

More recent developments have suggested a much larger shift in the federal government’s posture toward debt accumulation may be underway.

The Trudeau government has dramatically increased spending for the 2020 fiscal year to provide income supports and other assistance to governments, households and businesses during the pandemic and the related economic crisis. Of course, Canada is in the midst of an unprecedented fiscal and economic shock, and so it would be a mistake to read too much into the government’s overarching fiscal policy from this year’s large deficit.

More important to the question of whether there will be a lasting shift away from debt aversion is the Trudeau government’s signal that it will pursue additional large-scale deficit financed initiatives likely to require another large deficit next year and likely significant continued deficits after that. The proposed commitments go far beyond emergency funding for COVID-19 emergency programs and short-term stimulus by including new debt-financed spending on potential big-ticket items like national pharmacare, childcare, and ambitious green initiatives.

In short, the Trudeau government has signalled it is willing to accept meaningful growth in the federal debt-to-GDP ratio in the years ahead in order to pursue its key objectives, and that eliminating the deficit quickly will not be a high priority as it was in the years following the 2008-09 recession.

Furthermore, unlike the governments of Chrétien and Martin, the Trudeau government has not yet committed to providing timeline for a return to a balanced budget. No such forward planning is anticipated in the upcoming federal budget.

Despite these developments, there is reason to doubt that the Liberal government is in fact planning to challenge the long-standing federal government commitment to debt aversion. The Prime Minister has stated his government will “absolutely” return to balance at some point. It is possible that the government is simply committed to extensive COVID-related stimulus and then will return to a fiscal policy rooted in debt aversion within a few years.

Conclusion: Should Canadians Welcome Change?

In short, it is too soon to tell whether the Trudeau government’s recent commitment to historically large deficits this year and likely in the immediate following years will mark a lasting change in the federal government’s multi-decade focus on debt aversion. It is not, however, too soon to start asking whether the Trudeau government and/or its successors should adopt a different posture towards federal debt than has prevailed in recent years.

Opinions vary widely on whether such a transformative change in the nature of federal policymaking should be welcomed or condemned. For example, former clerk of the Privy Council and public finance expert Alex Himelfarb welcomes a transformative change. He argues that the federal government’s focus on tax cuts and fiscal restraint has “narrowed our sense of what’s possible, making it seem like big things were out of reach, unaffordable.” He argues that the federal government’s recent interventions have reminded Canadians after a long period of restraint that “government can be a force for good” and argues that the federal government can use debt-financed spending to “build a better world.”

Other analysts have argued that the old consensus served Canada well, allowing for competitive taxes, promoting growth, and reducing the amount of money spent on debt interest payments. Defenders of this approach have also argued that the fiscal policy approach described above is precisely the reason Canada entered the recession with so much fiscal capacity for emergency spending, thereby making it possible for the government to provide relief for individuals and businesses during the pandemic.

This debate is of crucial importance. If Canada’s debt-averse approach has in fact blinded us to policy options that could build a “better world” for Canadians, then a move away from it is something to celebrate. If the historical approach has promoted growth and saved Canada meaningful money on debt interest payments while creating fiscal capacity for emergencies, its disappearance would leave Canada worse off.

This commentary doesn’t seek to answer these questions but rather aims to draw in broad contours the nature of the debate that lies ahead and illustrate the extent to which it is anchored in recent federal fiscal history. The historical question of whether the consensus approach under multiple prime ministers of various political stripes over the past 35 years has served us well should be discussed, and the outcome of that debate will help determine where we go from here.

[1] It should be noted that we are very likely to see significant growth in federal spending relative to GDP in the years ahead because of the federal government’s approach to carbon tax revenue recycling. If large provinces continue to depend on the federal backstop to meet the federal government’s carbon price mandate in the years ahead, government expenditures will increase due to the associated lump sum transfers to households that will be booked as federal expenditures.