Miles Corak

This is the second commentary in a three-part series examining ideas for reforming Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) program. This commentary discusses the need for the EI program to provide comprehensive insurance against various forms of income loss. The First commentary, on the need for EI to be better designed to insure against big shocks, can be found here.

The COVID pandemic has fast-forwarded many changes in the way employers manage, monitor, and motivate their employees. The future of work is here and will involve more insecurity for many workers. The Canadian federal government can offer better and more appropriate income insurance by responding with both quick and easy, and with more fundamental changes to the Employment Insurance program.

The 2020 Speech from the Throne boldly claims that “This pandemic has shown that Canada needs an [Employment Insurance] system for the 21st century, including for the self-employed and those in the gig economy.” That is a tall order, a major overhaul of a complicated program in the span of the next couple of months, with little or virtually no consultation of stakeholders or engagement of experts outside of the government. Will Minister Qualtrough, her cabinet colleagues, and of course the Prime Minister, get it right? After all the need for EI reform has long been recognized, with lessons learned well before the onset of COVID19, but always politically convenient to put off. What does the 21st century hold for us? Well, we’ve seen a good deal during its first 20 years, and some big lessons are pretty clear. I draw three lessons, and these should be used to judge what the government has in store. You can read about the first here: Big shocks matter and need a response in real time. This post discusses the second and the reforms it calls for: Lesson 2 is “The future of work has arrived and needs better income insurance for all.”

Lesson 2: The future of work has arrived and needs better income insurance

I often wonder what has happened to Neil Piercey, the 58 year old man from London Ontario who walked, with a certain trepidation, into the Prime Minister’s office to speak to the newly elected Justin Trudeau during those heady days in the aftermath of the 2015 election.

Mr. Piercey was one of ten Canadians to engage “Face to Face with the Prime Minister,” as the CBC billed the televised series, each chosen to focus on a policy issue that touched their lives in a way representative of other citizens.

Mr. Piercey’s concern was “Manufacturing jobs in Canada,” and he may have walked in with trepidiation, but he spoke with a great deal of pluck about his plight as a laid-off factory worker who earned a decent income but now as a fruit delivery driver was struggling to piece together work that would give him some semblance of past security.

Savings exhausted, house sold, family disrupted, hard workers like Mr. Piercy were not well served by the first wave of free trade deals, and its attendant globalization of supply chains and contracting out that restructured many industries, particularly across large swaths of Southern Ontario’s manufacturing belt.

People like Mr. Piercey, those in the middle or tail end of their careers with significant seniority with the only employer they have likely known, took it on the chin and in the pocket book, suffering a permanent loss in their lifetime earnings. They were left carrying the cost of a social decision that benefited many, but left them uncompensated. Social policy makers and Finance Ministers at the time were telling these people that they should be “adjusting to win.”

But this man’s past, even now years later, teaches us important lessons about the “future of work,” lessons that still need to be taken to heart so that government has more to offer the next wave of Neil Pierceys than the Prime Minister could during that January 2016 encounter.

Mr. Piercey’s vote could go populist as easy as it might go progressive, and if the upcoming reforms to Employment insurance promised by the Speech from the Throne do not respond in an important way to his call for employment and income security, the reality of a policy agenda framed around “supporting the middle class and those working hard to join them” will more accurately be portrayed as “disappointing those treading to stay afloat and the middle class likely to join them.”

The Future of Work and the coming insecurity

The Speech from the Throne recognizes that the nature of work is changing and calls for coverage to be extended to the self-employed and to so-called “gig” workers.

With the exception of the COVID pandemic, the “changing nature of work” has to be—right up there with climate change—one of the hottest issues facing Canadians, a big cause of uncertainty and insecurity that underlies the middle class malaise that all political parties are hoping to address.

And quite rightly so. The future of work and globalization should raise a lot of anxiety.

Richard Baldwin’s 2019 book, The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics and the Future of Work, argues that as powerful innovations in digital technology meet globalization many higher paid workers in service jobs will be confronted with the disruptions that workers in manufacturing jobs had to deal with during the first wave of globalization during the 1990s.

His argument that its “coming faster than most people believe,” has been rendered all the more believable as the COVID pandemic has advanced the pace at which technology is changing our workplaces and families.

Many employers have made dramatic changes in the hard and soft technology of how they manage, monitor, and motivate their workers, learning that working at home may disrupt productivity, but in many cases may do just the opposite if done right. If that is the case, then how long before your boss starts asking: “If you can do your job anywhere, can anyone do your job?“

This is Professor Baldwin’s argument, that advances in communication technology are going to lead to another wave of globalisation and contracting out, but this time moving past manufacturing into the service sector, impacting many white collar workers. Many of them are relatively well-paid but they will likely be brought into head-to-head competition with equally skilled programmers, accountants, purchasing agents in other countries happy to work for a much lower wage.

What then should politicians be doing about this future which COVID has made to look like its just around the corner? Neil Piercey’s experience teaches us that the first step is not more training and exhorting mid-career workers to “adjust to win,” but rather it is to offer better insurance, compensating for the loss of firm-specific skills that have lost their utility when employers have gone belly-up.

Quick and easy reforms for better insurance

Quick and easy reforms to the existing Employment Insurance program involve increasing the fraction of income replaced by benefits in the event of job loss. The “replacement rate” is the result of two dials in the EI program that the federal government can easily notch up: the benefit rate and the maximum insurable earnings.

The benefit rate is currently 55%, meaning that an EI claimant receives 55 cents for every dollar of insurable earnings. This rate has varied from as high as 80% for certain categories of claimants to the current low, and is set by the government with an eye to keeping costs in line, and nominally to promote “work incentives,” encouraging workers to look harder for a job and move more quickly off the EI books. These past priorities don’t serve our present and future well.

There is a long history of legislative changes to this rate. The 1971 legislation introduced a major reform to all aspects of the program, and raised the benefit rate to 66 2/3 % from 40%, even offering a rate of 75% to claimants with children for the first two phases of a five phase benefit period. There were several reforms in the following decades, but the 1996 reforms significantly cut the benefit rate. It has been cut further since, now standing at 55% of insurable earnings. That said, the “Family Supplement” was also re-introduced by this legislation and has varied from as low as 65% to currently as high as 80% for some select groups of low income claimants with families.

My point is that given this history of change that sometimes quite sharply lowered the benefit rate in the name of deficit fighting and work incentives, it is both feasible and timely to raise the benefit rate and offer workers better insurance by covering more of their past earnings. Having roughly half of previous earnings covered is not the support that long-time contributors to the program facing the challenges of the future of work will expect.

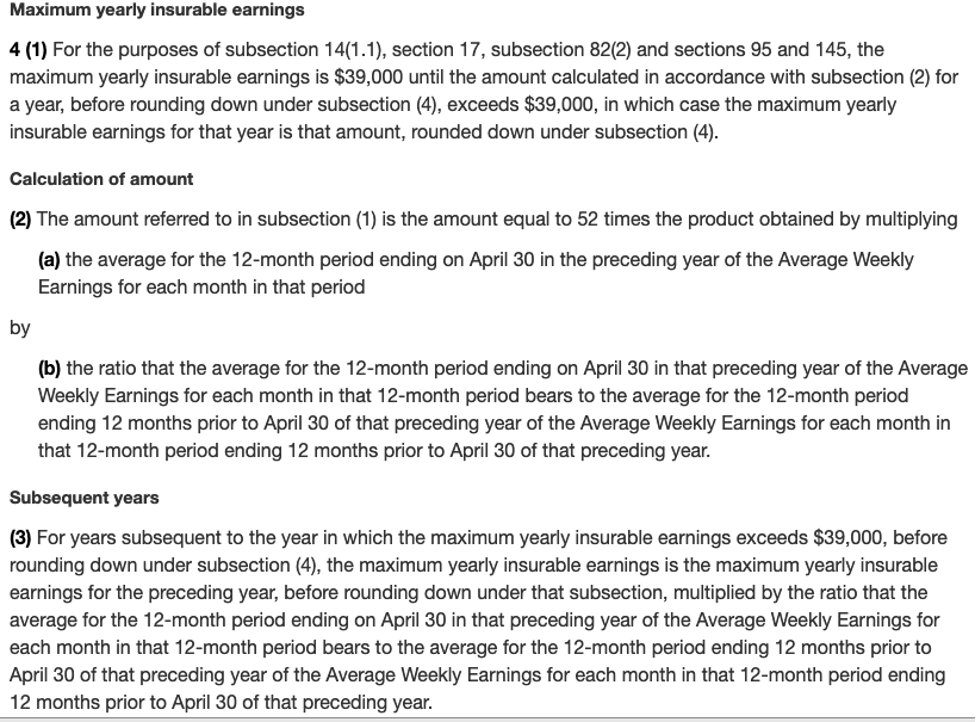

But to suggest that claimants have roughly half of their previous earnings replaced by EI benefits is to overstate things. Earnings are replaced by benefits up to the “Maximum Insurable Earnings,” which is currently an annual income of $56,300. This maximum was set at $39,000 in the 1996 legislation that currently governs the program, and updated annually according to movements in Annual Average Earnings as determined for the “Industrial Aggregate” from a monthly Statistics Canada survey.

So workers making more than the average face even a lower benefit rate, EI likely compensating them for less than half of their accustomed income. In other words, there is a whole bunch of relatively well paid workers, much like the manufacturing workers of Neil Peircey’s time, facing a lot more insecurity in their future, but being offered less than adequate insurance.

The calculation of the maximum insurable earnings is not as complicated as the EI legislation makes it appear: basically take the average weekly earnings last year, and scale it up or down by how much it has changed over the year before that. The point is that it is an easy legislative change to scale it up to be based, say, on one and a half times the average.

Increasing the maximum insurable earnings significantly above the average and raising the benefit rate will increase the replacement rate of incomes and offer workers more complete insurance and foster their sense of security in a more and more uncertain future. These are quick and easy legislative changes the government can make without fuss.

Wage insurance not just employment insurance

An important change that might be a bit more “fuss,” in the sense of requiring more fundamental administrative changes to the EI program, has in fact already been promised by the government in its election platform, and figures in Minister Qualtrough’s original mandate letter:

“Create a new Career Insurance Benefit for workers who have worked for the same employer for five or more years and have lost their job as their employer ceases operation. This new Benefit will begin as Employment Insurance ends and will not be clawed back if other income is earned”

This is an important and very relevant change to Employment Insurance to address the future of work, enhancing regular benefits in a way that will offer insurance not just for the time unemployed in the search of a new job, but also for the income loss from taking a lower paying job.

This is a mild form of “wage insurance“, and will take an innovative step in making Employment Insurance more relevant for many workers, who may never have collected benefits in the past and are laid off from jobs that they have held for at least five years. It involves paying benefits to laid-off workers after they have accepted a job. The benefit would cover some significant fraction of the difference between their current and past incomes, for some significant period of time.

The government should proceed full throttle on this reform, and indeed even enhance it and make it more significant than originally imagined. Giving some workers strong wage insurance for an extended duration will offer them income security, and help many long-tenure mid career workers adjust to a future of lower pay. You could call it, at least in spirit, “Neil’s benefit.”

What I’m trying to say in all of this is that our current Employment Insurance program does a good job at insuring small risks and offering regionally-based income support, but falls short of insuring potentially big losses. That is a major shortcoming as a wave of big losses is likely coming.

As consumers our welfare depends much more on insurance for losses of potentially catostrophic consequences for our assets: we look to solid home insurance, and worry less about our bicycles. And so as workers, facing the transition to a new economy, we will increasingly need comprehensive income insurance, not partial and small scale employment insurance.

The future of work calls for better income insurance.

This is a slightly revised version of a commentary that was originally published on Miles Corak’s personal website.