| Dataset | |

| Download Paper |

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, first a major health emergency, quickly turned into an unprecedented economic crisis, caused by government-imposed containment measures and shutdown of the economy to curb the spread of the virus. This prompted states to intervene as never before since World War II. In Canada, the first economic interventions came from the Bank of Canada to stabilize a financial system “under extreme stress”.[1] Around the world, central banks’ response to the financial and economic crisis has been aggressive and rapid. On March 4, the Bank of Canada announced the first of three cuts to its benchmark interest rate.

This analysis seeks to recount how Canadian governments have responded, through the economic measures announced until May 15, 2020,[2] to the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. It breaks down the federal and the provinces’ fiscal and budgetary response into two phases: first the emergency measures, then the mitigation measures. The announcements made on March 25 by the Government of Canada represent the pivotal point between the two periods.

A synthesis of the various measures introduced follows, including a discussion of the costs of the governmental support to businesses and individuals. Finally, Canada’s response is briefly compared to measures taken by other OECD countries.

1. Responding to the Virus Outbreak

This first part of the paper identifies government interventions up to March 25, 2020, which focused on the response to the virus outbreak directly. Initially, the priority was to increase the capacity of health systems to face the pandemic. Across the country, resources were mobilized to purchase protective equipment and strengthen testing capacity. On March 11th, the Prime Minister of Canada announced the creation of more than $1 billion fund to finance public health and research spending, including $500 million for the provinces. The message was clear: “Financial considerations should not and will not be an obstacle to hospitals and health systems making the necessary preparations.”[3]

It quickly became apparent that financial considerations would not hinder support for individuals and businesses. A few announcements were made by the federal government on March 11th, but the first substantial measures were revealed the following week. Later, the federal government established that the crisis had begun to affect Canadians as of March 15th by retroactively starting its two main employment support programs on that date.

The provincial governments, which have constitutional jurisdiction over health and education, successively closed elementary and secondary schools and declared a state of emergency.[4] As of March 25th, nonessential businesses were shut down in five provinces, including Ontario and Quebec.

1.1 Income Support for Individuals

The federal government’s first measure to support individuals was to accelerate EI sickness benefits for workers in quarantine or forced to self-isolate. Prime Minister Trudeau indicated that additional help for other affected Canadians was under consideration; these measures were announced seven days later.

In the meantime, provincial measures targeted emergency support, more specifically for workers directed to self-isolate who did not qualify for Employment Insurance (EI) benefits. Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Alberta and Saskatchewan quickly implemented temporary programs to this end. In Alberta and Quebec, the support offered was equal to the maximum amount of EI, but the Alberta program was broader in scope as it extended to workers caring for a dependent in isolation[5].

The support offered by the provinces was very short term and meant to bridge the period until the Government of Canada announced its own program. This federal announcement came on March 18 in the form of two new emergency allowances, the Emergency Care Benefit and Emergency Support Benefit, which were projected to cost up to $10 billion and $5 billion respectively.[6] The first was intended for workers who were sick, quarantined or who had to stay home to care for a family member and it provided $450 a week, for up to 15 weeks. The second targeted non-EI-eligible workers facing unemployment as a result of the pandemic; its parameters were to be comparable to those of EI.

Most of the emergency support programs announced afterwards in British Columbia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia were intended to bridge the gap until those who suffered a loss of income received federal assistance[7].

Broad-based relief measures to reduce pressures on household liquidity have also been put in place by the provinces and the federal government. The most substantial were announced on March 18th, when the federal government extended the filing and payment deadlines of personal income tax returns. Quebec, the only province administering its own income tax, quickly followed suit.[8]

In Alberta, the government cancelled the planned increase in Education property tax rates. Relief was also announced for utility bills in a few provinces.[9]

In response to the pandemic, many cities have delayed property tax payments[10], which represent their largest source of revenue.

Other measures put in place at the beginning of the crisis targeted vulnerable groups. For seniors, the Government of Canada reduced the minimum withdrawal from a Registered Retirement Income Fund (RRIF) by 25%, at an estimated cost of $495 million[11], and Quebec aligned itself with the measure. For Canadians with student debt, the federal government implemented a six-month payment moratorium during which no interest will be calculated ($190 million).[12] Provinces quickly harmonized with this measure for their student loans.[13]

To further increase household liquidity, the maximum annual amount of the GST credit was doubled, a measure estimated to cost $5.5 billion.[14] Simply qualifying for the GST credit was sufficient to receive the special lump-sum payment; no loss of income caused by COVID-19 was necessary. In addition, given the parameters of the measure, 1.5 million new beneficiaries were added.

The federal government’s assistance also targeted families with children. Those eligible to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB) were granted an additional $300 per child benefit, including those with high income or facing no earning losses ($2 billion[15]).

One-time increases in transfers to low and modest-income families, seniors and households were also announced in Ontario, Nova Scotia and British Columbia. In this last province, a measure announced on March 25 targeted lower-income tenants facing income losses and provided rent assistance to their landlords[16].

1.2 Liquidity Support for Businesses

The first measure to preserve economic relationships between workers and firms was introduced by the federal government on March 11th by enhancing the EI Work-Sharing program.[17] While other provinces were about to announce their first support measures for workers, the Newfoundland government announced a “compensation to private employers to ensure continuation of pay”[18] for employees affected by the self-isolation directive for persons returning from abroad. However, most of the measures that followed were intended to support businesses cash flow through increased credit availability and easing measures.

On March 13th, the federal government announced the establishment of the Business Credit Availability Program (BCAP), a $10 billion program to provide financing solutions to businesses, including SMEs. A few days later, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia created or enhanced programs to facilitate small businesses’ access to credit[19]. A new temporary program providing emergency financing to businesses affected by the impacts of COVID-19 was announced in Quebec on March 19th. The Atlantic provinces and Québec also instituted moratoriums for the repayment of government loans.

In this emergency phase, the most significant cash flow support measures took the form of tax payment deferral. The federal government announced the postponement of corporate income taxes and instalments on March 18th, and the provinces that administer their own corporate income tax, namely Alberta and Quebec, quickly aligned with the measures. Saskatchewan and Manitoba were the first to extend deadlines for sales tax remittances, while in British Columbia and Ontario, payment deferrals were introduced for various other indirect taxes. Easing measures for payroll taxes were also implemented in Manitoba, British Columbia and Ontario. Toronto and Montreal announced property tax deferrals for businesses, as did many other local governments throughout the country[20].

Employer payments to the Worker’s Compensation Board (WCB) were quickly deferred in Nova Scotia and Quebec[21]. Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario[22] announced utility bill easing measures for agricultural and commercial customers. On March 20th, Nova Scotia’s Government declared that small businesses would be paid within 5 days instead of 30.

Some provinces also froze or reduced tax rates. British Columbia delayed provincial sales tax changes and the carbon tax increase planned in its 2020 Budget, and lowered school tax rates for commercial properties.[23] In Alberta, small and medium businesses’ WCB premiums for 2020 were reduced by 50% and their payment deferred to 2021 for all employers. In Ontario, the Employer Health Tax exemption was increased for 2020 to include more than 90% of private sector employers.[24]

Canadian governments also introduced new programs to preserve employment ties.One week after the expansion of the EI Work-Sharing program, the Government of Canada announced a 10% wage subsidy to support small businesses experiencing income losses and to “prevent lay-offs.”[25] All businesses benefiting from the Small Business Deduction[26] could quickly obtain this three-month subsidy by reducing their employee’s income tax deduction remittances. On the same day, Prince Edward Island unveiled a temporary allowance paid to the employers of workers facing a reduction in their working hours.

Some early support measures targeted vulnerable industries. For farmers and agri-food businesses struggling with cashflow issues, the Federal Government announced a $5 billion increase in Farm Credit Canada lending capacity. A six-month deferral for farmers with outstanding Advance Payments Program loan as of April 30 was also implemented.

In the oil-producing provinces, the effects of the pandemic were compounded by the drop of commodity prices and further eroded the economic outlook. Unable to borrow the necessary funds “to maintain the operations of government,”[27] the Premier of Newfoundland turned to his federal counterpart on March 20th to call for urgent action. [28]In Alberta, the Government quickly announced relief measures for the energy and mining sectors.[29]

2. Responding to Containment Measures and the Lockdown of the Economy

March 25th was a pivotal date in governments’ response to the crisis, with the Federal Government unveiling the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). This announcement marked the beginning of a second phase of governments’ interventions. From this point, most announcements would expand the scope of the existing measures to prevent containment from causing too much damage to the labour market and the economy’s production capacity.

2.1 Mitigating the Economic Impacts of Containment Measures on Households

One week after introducing the Emergency Care and Support Benefits, the Government of Canada replaced the two programs by the CERB. Delivered through the CRA, it provided a taxable amount of $500 per week for a maximum of 16 weeks to eligible workers who had stopped working for reasons related to COVID-19.

In the days that followed, temporary emergency benefits were introduced in Prince Edward Island[30] and in Nova Scotia to bridge with the CERB. British Columbia announced an increase of $300 per month for all beneficiaries of provincial income support non-eligible for federal emergency programs[31].In response to the implementation of the CERB on April 6th, the governments of Quebec and Alberta terminated their more restrictive emergency support program for workers. Nearly 80,000 workers used the Alberta program ($91 M[32]) compared to 13,000 in Quebec ($14.5 M[33]). It was also on April 6th that the CERB was extended to SME owners who pay themselves through dividends.

Rather quickly, the financial support obtained through the CERB was compared to the income earned by those working at the minimum wage; in Quebec, in April 2020, 40 hours a week were necessary to earn a gross income equivalent to the CERB. Given the possible impacts of lower-income workers’ incentives to work, on April 3rd, the Government of Quebec announced the Incentive Program to Retain Essential Workers (IPREW),[34] a temporary taxable benefit of $100 per week targeting essential services employees earning $550 a week or less[35]. Wage premiums for employees in the health care sector have also been introduced, as in other provinces.[36]

On April 15th, CERB eligibility was extended to seasonal workers as well as those who had exhausted their EI benefits. In addition, it was announced that recipients could earn up to $1,000 per month without losing the benefit. At the same time, the Federal Government indicated that a new transfer would be made to the provinces and territories to share the costs of a temporary wage top-up program for essential low-income workers, such as Quebec’s IPREW. Estimated at $3 billion, the federal participation was to equal 75% of the agreement’s costs, and each province was to determine eligible workers and top-up amounts[37]. In addition to Quebec, Saskatchewan, and Prince Edward Island[38] announced programs for low-wage essential workers. In other provinces, wage premiums were implemented for health care or front-line workers, such as in Nova Scotia and British Columbia[39].

By allowing those who benefit from the CERB to earn up to $1,000 per month, the Government broadened its access, especially to self-employed workers who have suffered significant but not total income losses. However, as provinces gradually relax containment measures, the CERB’s negative effects on incentives to work have been criticized by many.[40] For example, for workers earning less than $3,000 per month, working part-time while benefiting from the CERB is more lucrative than working full-time.[41]

In this second phase of policy responses, new targeted measures for students and seniors were introduced.New Brunswick and Saskatchewan introduced emergency support programs for post-secondary students directly affected by the pandemic who were not eligible for other financial assistance programs.[42] On April 22nd, the Federal Government announced several measures to support post-secondary students, including the creation of the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB), estimated to cost $5,25B[43]. Available from May to August 2020, this measure closely related to the CERB provided $1,250 per month to students and recent graduates unable to find a full-time job due to the pandemic.[44]

A few days before the CESB announcement, the Government of Quebec unveiled a program to support the recruitment of agricultural workers ($45M), including a wage premium of $100 per week.[45] One of the program’s objectives was to encourage the hiring of students. However, the introduction of the CESB, like the CERB, reduced the incentive to earn more than $1,000 a month and partly cancelled the expected effect of the Quebec program.[46]

Furthermore, while the precarious financial situation of many students cannot be denied, the CESB offered them a compensation for an income loss that had not yet materialized. At the same time, some workers facing unemployment due to the pandemic were not eligible for the CERB, for example because their 2019 employment income was under $5,000.

The Government indicated that efforts would be made to ensure that the CERB and CESB meet their financial support objectives while encouraging employment in all circumstances.[47] It is possible that these benefits will be adapted towards this end in the future, but as of today, nothing has been announced in this regard.

On May 5th, Manitoba introduced a $200 refundable tax credit for seniors. A federal measure to help seniors “get the support they need during the pandemic”[48] was announced the following week: a $300 tax-free lump sum payment to those eligible for the Old Age Security (OAS) pension plus an additional $200 for seniors eligible for the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) ($2.5B).

Like the one-time GST credit and CCB enhancements, no loss of income due to COVID-19 is required to receive the payment; all beneficiaries automatically qualify. The GIS is specifically targeted to low-income seniors, but all Canadians receiving the OAS will receive $300, regardless of their income. In this last case, the nontaxable nature of the amount appears harder to justify.

2.2 Shutting Down the Economy: Strengthening Business Cash Flow and Preserving Productive Capacity

In the second phase of the Government’s response to the pandemic, the measures for businesses became more generous and were extended to a larger number of firms. The priority was to avoid business closings or bankruptcies and to preserve economic relationships. In addition to the support for the agricultural and energy sectors, the measures also targeted economic activities most significantly exposed to the impacts of containment measures and social distancing, such as the tourism and cultural industries.

On March 27th, the Federal Government announced a new 75% wage subsidy, the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS). By relying on the payroll mechanism to support workers’ income, the subsidy aimed to preserve employment ties and to facilitate the recovery of economic activities.

The initial terms and conditions of the CEWS were revealed on April 1st: a 75% taxable wage subsidy targeting companies that had experienced a significant decrease in revenue due to the pandemic, capped at $847 per employee per week, for a maximum period of 12 weeks (then extended by an additional 12 weeks on May 15th)[49]. The 10% wage subsidy remained available, especially for businesses unable to qualify to the CEWS.

At the provincial level, Nova Scotia[50] and Saskatchewan announced one-time grant programs targeting small businesses. The Government of Quebec introduced PACME, a subsidy program to help businesses cover the costs of training their employees, among other things. In Newfoundland, the hiring eligibility and contribution levels of the R&D assistance program was temporarily increased, retroactively to April 1st. Manitoba announced a $7 per hour wage subsidy on April 24th to encourage summer student hiring.[51]

Additional relief measures were announced by the provinces and the government of Canada. On March 27th, the federal government also announced the deferral of GST/HST tax remittances (Quebec did the same for QST). In Quebec, the government has postponed the dates for the remittance of the accommodation tax, a support measure for the tourism and hospitality sectors, which have been particularly affected.

In addition to the easing measures deployed in several cities across the country, New Brunswick and British Columbia have announced relief for the property taxes under their management. At the same time, the relief provided by municipalities will necessarily affect their revenues, and some provinces have taken measures to mitigate this impact.[52] In Manitoba, restaurants have been offered a payment deferral on their liabilities toward Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries.[53] In addition, the Government is accelerating the removal of $75 million of annual provincial sales tax from property insurance, and the Workers’ Compensation Board will return its $37 million surplus to eligible employers as a credit amounting to 20% of contributions paid in 2019.[54]

A first expansion of federal emergency loans was also announced on March 27th. The Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) provides up to $40,000 in interest-free loans to small businesses and non-profit organizations. Upon its initial announcement, the Government indicated that if repayment of the loan is made by December 31, 2022, 25% of the loan would be forgiven, up to a maximum of $10,000. In addition to this $25 billion cash support program[55] there are two SME loan programs, with combined financing opportunities of $40 billion. A few days later, Quebec in turn expanded its business financing offering by introducing a working capital loan program for small and medium-sized enterprises, with an initial envelope of $150 million.

On April 16th, the Federal Government announced that more businesses would qualify for CEBA[56]. The next day, more than $1 billion in funding was announced through two programs for businesses unable to access a loan through CEBA or to qualify for the wage subsidy program.[57] In May, the Large Employer Emergency Financing Facility (LEEFF) was implemented as well as a new expansion of the Business Credit Availability Program to address greater financing needs. On the provincial side, Manitoba and Nova Scotia created loans and grants for businesses that are not eligible for federal measures.[58]

Landlord-tenant relations are a provincial responsibility and as of March 27th, the Nova Scotia government introduced a program to encourage landlords to defer rent payments from their struggling commercial tenants;[59] Prince Edward Island’s program was announced three days later.

On April 16th, the Government of Canada announced the creation of Canada’s Emergency Commercial Rent Assistance (CECRA) and confirmed the following week that an agreement in principle had been reached with the provinces and territories (a 75% federal-25% provincial cost-shared program). This program, administered by the CMHC, combines loans and grants to owners of mortgage-backed commercial buildings to lower the cost of rent for struggling small businesses.[60] Building owners who participate in the program must absorb at least 25% of rental costs.

Additional measures were announced for specific sectors or industries.On March 31st, the Alberta government announced a $1.5B investment in the Keystone XL pipeline project.[61] It subsequently delayed the payment of stumpage fees to support cash flow and employment in forestry companies, as did the Government of British Columbia. Saskatchewan implemented a series of relief measures for the provincial oil and gas sector ($11.4M).[62] To support employment in the energy sector, a federal support of $1.7B in Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia to repair natural environments was announced on April 17, along with the introduction of a $750 million repayable loan program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from conventional and offshore oil and gas companies.[63]

In the wake of those plans, a $500 million emergency fund was also announced for temporary assistance to the cultural, heritage and sports sectors. As for the provinces, Prince Edward Island and Quebec have provided loans and relief to the tourism and agricultural sectors respectively. New Brunswick has launched a program that provides up to $2,000 to support virtual cultural performances by eligible artists, businesses and cultural organizations.

On May 5th, the Federal Government announced new support measures for the agri-food sector at a cost of $252M, as well as a $200M increase in the Canadian Dairy Commission’s borrowing limit. For fish harvesters who suffered income losses, emergency loan programs and interest relief programs were put in place in Prince Edward Island. A week later, the Fish Harvester Benefit was unveiled by the Federal Government. This applies to fish harvesters who are not entitled to the CEWS and who are facing a decline of more than 25% in their fishing income. The Federal Government also announced a grant program of up to $10,000 for self-employed fish harvesters who are not eligible for CEBA or equivalent measures.[64]

3. Cost of Support Measures

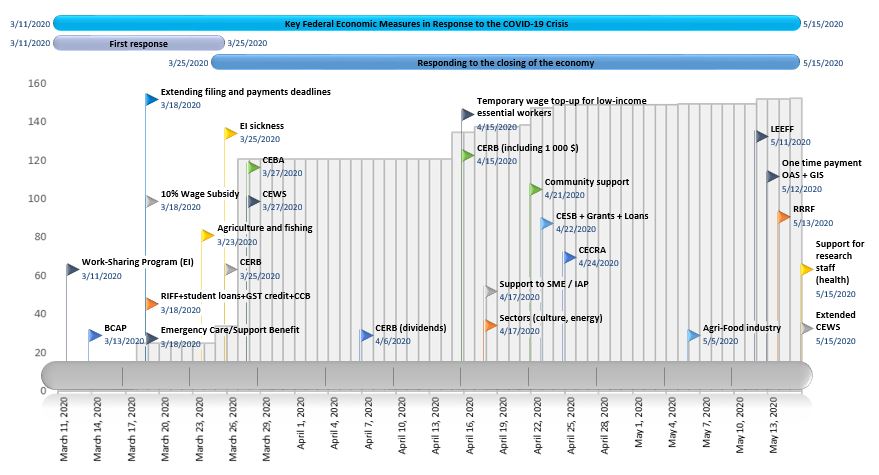

As of May 15, 2020, the Government of Canada had announced more than $150 billion in direct assistance measures for businesses and households. Figure 1 displays numerous federal announcements made since March 11th. In the background, a graph shows the cumulative day-to-day costs of programs, when this information is available.

Figure 1: Timeline and cumulative costs (G$) of key federal economic measures

The largest jumps on the curve reflect the cost of the CERB announcement on March 25th, part of which was announced on March 18th with the two emergency benefits, as well as the CEWS announcement on March 27th. No cost is added for measures facilitating businesses’ access to credit or for deferrals of tax payments unless they were assessed by the Federal Government.[65]

Easing measures. Table 1 presents the main tax easing measures announced; the dates shown refer to the first announcements.

Table 1. Summary of easing measures

| Individuals | Businesses | ||||||

| Income tax | Income tax | Sales taxes | Other indirect taxes | Payroll taxes | Social contributions | Others [1] | |

| FED | March 18 | March 18 | March 27 | ||||

| BC | March 23 | March 23 | March 26 | April 16: School taxes April 28: Timber dues | |||

| AB | March 18 | March 23 | April 4: Timber dues | ||||

| SK | March 20 | March 30 | |||||

| MB | March 22 | March 22 | April 3 | ||||

| ON | March 25 | March 25 | March 25 | April 6: Property taxes | |||

| QC | March 17 | March 17 | March 27 | April 9 [2] | March 20 | ||

| NB | March 26 | March 26: Property taxes | |||||

| NS | March 20 | ||||||

| PE | March 24 | April 3: Property taxes | |||||

| NL | April 9 [3] | April 7 | March 24 |

For major federal easing measures, deferrals granted to support taxpayers’ liquidity are estimated at $85 billion, or $55 billion for income tax[66] and up to $30 billion for GST and duties.[67] However, since these are deferrals, the final tax loss will be minimal relative to the amount announced. The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) estimates this loss at $679[68] million for income taxes and $92 million for GST[69]. The cost essentially reflects borrowing cost for the Government, interest and penalties not collected during the deferral period as well as additional defaults resulting from the crisis.

In Quebec, the deferred payment of personal and corporate income taxes is estimated at $8.6B, the deferral of QST remittances is estimated at $7.3B, and accelerated payments of some business tax credits, at $600M.[70] In Ontario, business carry forwards are estimated at $7.9B.[71]

In addition to tax relief measures, some provinces have frozen or reduced taxes that mainly affect businesses. Table 2 summarizes the estimated cost of these measures.

Table 2. Provincial Tax Freezes and Reductions

| Sales taxes | Other indirect taxes | Payroll taxes | Social contributions | Others | |

| FED | May 6 : $281M [1] | ||||

| BC | March 23 [2] | March 23 [2] | March 23: $700M | ||

| AB | March 23: $350M | March 23: $87M [3] | |||

| MB | April 3: $75M [3] | April 21: $37M | |||

| ON | March 25: $355M [4] |

Measures for businesses. Table 3 presents other support measures for businesses. Costs in dollars ($M or $B) reflect preliminary governments’ estimates of the direct costs of measures. The amounts in parentheses correspond to the financing offered to businesses through various loan or loan guarantee instruments. As in the case of carry forwards, much of the money available to businesses is not equivalent to government spending. For interest-bearing loans, the net effect could be positive due to additional interest revenue.[72]

Table 3. Summary of Business Support Measures

| Access to financing | Other liquidity support measures | Job support | Business support | Commercial leases | ||

| FED | BCAP (81.3B) CEBA: $13.8B LEEFF RRRF (962M) | IRAP: $250M | EI: $12M 10% WS: $1B CEWS [1]: $45B | Agriculture (5.2B): $252M Energy (0.8B): $1.7B Culture: $500M Fish harvesters: $469M Research: $450M | CECRA : $3B | |

| BC | CECRA: $80M | |||||

| AB | Invoices | Energy (113M): $1.5B Mining agreements | CECRA | |||

| SK | SSBEP: $50M Invoices | Energy: $11.4M | CECRA | |||

| MB | Subsidy: $120M Invoices | Student jobs: $120M | CECRA | |||

| ON | Electricity rate: $1.5B [2] | CECRA: $241M | ||||

| QC | PACTE (2.5B) Emergency aid to SMB (150M) | Deferrals | PACME: $200M | Agriculture | CECRA: $137M | |

| NB | Working capital loans (50M): $19M | Deferrals | Culture | CECRA | ||

| NS | Loan guarantees (161M) SBCSP (20M): $3M | SBIG: $20M Deferrals Delays | Rent deferral CECRA: $9M | |||

| PE | Working capital loans CBDC (4.5 M) | Deferrals | Emergency relief | Tourism (50M) Fisheries (250M) | Rent deferral: $1.5M CECRA | |

| NL | Deferrals Invoices: $2.5M [2] | Self-isolation Grants for student jobs R&D | CECRA | |||

However, the interest-free loans offered will result in interest charges to the Government, plus, in the case of CEBA, the cost of writing off 25% of the loans repaid by December 31, 2022 ($13.75 billion).[73]

The direct cost of federal measures totals more than $64 billion, including $45 billion attributable to Canada’s Emergency Wage Subsidy.[74] As of June 1, 2020, $9.4B had been paid to businesses in wage subsidies, covering over 2.5 million workers.[75]

In the provinces, cost estimates are not available for all programs, but some provinces have indicated overall amounts. In Prince Edward Island, on May 14th, the Government estimated the cost of business assistance measures at $40 million.

Table 4 summarizes the various measures to support individuals. The assistance comes mainly in the form of payments to workers affected by COVID-19 or as lump sum enhancements of existing transfers. Costs are indicated based on availability of information.

The CERB is at the heart of federal assistance to households affected by COVID-19, and accounts for most of the cost of the direct support measures for individuals announced as of May 15th. While on March 18th, the cost of the two emergency benefits was estimated at $15 billion or less, the estimated cost of the CERB reached $24 billion on March 25th, $35 billion a month later[76] and $60 billion on May 28th,[77] bringing the total cost of support measures to more than $82 billion.

Table 4. Summary of measures to support individuals

| Emergency support | For eligible families or individuals | For students | For the elderly | For essential workers [1] | Rental assistance | |

| FED | CERB [1]: $60B | CCB: $1.9B GST: $5.5B | Existing loans: $0.2B CESB: $5.3B Canadian loans: $1.9B Grants: $0.9B Youth employment: $0.7B | RRIF: $0.5B OAS/GIS: $2.5B | $3B | |

| BC | Emergency Benefit for Workers | Climate Action Crisis Supplement Special Needs | Existing loans | Crisis Supplement | X | Rental Supplement |

| AB | $91M | Existing loans | X | |||

| SK | $10M | Existing loans: $4M Emergency support: $1M | $56M | |||

| MB | Existing loans | $45M | ||||

| ON | $300M | Existing Loans | $75M | X | ||

| QC | $14.5M | Existing loans: $48M | RRIF | IPREW: $890M Agricultural: $45M | SHQ Temporary housing | |

| NB | $4.5M | Existing loans Emergency support | ||||

| NS | Bridge Fund: $20M | $2.2M | Existing loans | $13M | ||

| PE | Income Relief Income Support Special Situations: $1M | Existing loans Farm Team | $17M | $1M | ||

| NL | Existing loans |

4. How Does Canada’s Response Compare to Other Jurisdictions: An Overview

According to the PBO[79], the federal government’s deficit could reach more than $252 billion in 2020-2021 or 12.7% of GDP, up nearly 12 percentage points since the previous projection. In many countries, public deficits are at historic levels. The Italian government estimates its deficit at 10.4% of GDP[80]. In the United Kingdom, public sector net borrowing is estimated at 15.2% for 2020-21[81], while in the United States, the federal deficit alone could total 17.9% of GDP[82].

In Canada, the federal economic response was built around two measures designed to support workers’ income: the CERB, for those who had lost most of their income, and the CEWS, to provide support to businesses suffering from revenue losses and help them keep their employees on the payroll. As of May 6th, 34 of the 37 OECD member countries had implemented some form of support intended for employees or self-employed workers facing income losses[83], while 22 of them offered wage subsidies for businesses[84].

However, the CERB, a made-in-Canada response to the crisis, is almost unique.[85] Many countries that already had an unemployment insurance system achieved a similar result to the CERB by changing their existing rules. The main objectives of the changes were to temporarily extend eligibility to self-employed workers, to relax the insurable hours criteria or their equivalent, to eliminate the waiting period, to increase the maximum benefit level, to exclude the crisis period from the duration of regular benefits or to extend the benefit period, to eliminate the criterion of active job search during the crisis. In short, many other countries did what Canada could have done if its EI system had been able to deal with an explosion of claims.

Some countries opted for a lump-sum payment or a specific program for self-employed workers rather than extending EI. A few countries paid lump sums to taxpayers who had suffered a loss of income or to all individuals below a certain income threshold, such as the United States.

In the case of the CEWS, which targeted companies facing revenue losses, it is comparable to measures implemented in a handful of OECD countries. In Australia and New Zealand, subsidies were fixed. In the United States, Ireland and the Netherlands, they are based on compensation paid, like in Canada.

Sixteen OECD countries offered other types of wage subsidies to businesses. They took the form of subsidies specifically targeting employees with COVID-19, of compensation related to the payment of hours not worked, or of subsidies based on revenue losses and payroll.

The Government of Canada has also enhanced existing transfer programs (GST, CCB, OAS and GIS) to provide direct support to their beneficiaries, regardless of whether they had experienced a loss of income or not. This practice does not appear to be widespread in OECD countries, but Australia and the United Kingdom have made additional payments to individuals and families already receiving certain benefits.

The vast majority of OECD countries have adopted tax relief measures. Thirty countries, including Canada, have deferred the production or payment of personal income taxes[86]. Businesses have benefited from a wider range of easing measures.[87] Of the 37 OECD member countries, 34 allowed a deferral of corporate income tax payments. Also, 18 countries, including Canada, granted a delay in the payment of consumption taxes. In addition, 20 countries offered relief measures for the payment of payroll taxes. Some countries have announced the acceleration of direct or indirect tax refunds by implementing new mechanisms or by allowing changes to the reporting schedule.

Finally,[88] in OECD countries where property taxes account for the lion’s share of local government revenues, cities’ response has taken the form of deferred property tax payment, as it did in numerous Canadian cities. Other major actions generally resulted from funding from another level of government.[89]

Conclusion

The economic response of Canadian governments to the COVID-19 crisis unfolded in two parts: first to deal with the health emergency and then to respond to the shutdown of the economy. This analysis shows that Canadian governments have acted quite rapidly and that, by expanding emergency measures, they have tried to help just about everyone. More often than not, the interventions of both levels of government were complementary, but some contradictions arose.

Overall, Canada’s response is consistent with the trends observed in most OECD countries. The information available on the costs remains fragmented and these will have to be better documented at the time of the final assessment. However, the importance of this aid is undeniable. On April 30th, the PBO estimated that federal spending alone in response to COVID-19 was over $150 billion or 7.7% of GDP. That does not take into account the expenditures announced since then or those made by the provinces. Additional spending will be needed for economic recovery, but also for a possible second wave of the virus.

On May 15th, when Bill Morneau announced the extension of the CEWS, he indicated that all upcoming adjustments would aim to “Promote jobs, promote growth.” Future actions must send a clear message about the need to gradually return to a more “normal” pace, with everyone’s participation. The support measures that will inevitably remain in place will need to be better targeted.

Finally, governments must eventually review the interventions implemented to respond to the emergency in order to identify what went well and what did not. They also have to carry out audits to make sure the money went where it was supposed to go. Learning from this unprecedented situation will be critical to improve the resilience of the fiscal system and to ensure we do better next time. By summarizing the governments’ response, this text can serve as a basis for this upcoming review.

[1] Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report – April 2020, 2020, at 5.

[2] But does not pretend to be exhaustive.

[3] Canada, Prime Minister outlines Canada’s COVID-19 response, March 11, 2020. https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2020/03/11/prime-minister-outlines-canadas-covid-19-response

[4] Quebec was the first province to declare a state of emergency, on Saturday, March 14th. Nova Scotia was the last one to do so, on March 22nd. Charles Breton and Mohy-Dean Tabbara, How the provinces compare in their COVID-19 responses, April 22, 2020. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2020/how-the-provinces-compare-in-their-covid-19-responses/

[5] Information from press releases. In general, when the information comes from press releases, the reference is not indicated. If necessary, contact the authors.

[6] Government of Canada, Prime Minister announces more support for workers and businesses through Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, March 18, 2020.

[7] British Columbia announced a lump sum payment of $1,000 for individuals who suffered a loss of income in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, including those who were eligible for federal programs. Up to April 30th, New Brunswick offered $900.

[8] Quebec first announced on March 17th the postponements of income tax filing and payment dates; it harmonized its deadlines with the federal government on the 19th.

[9] In addition, those who have lost their jobs, are sick or have suffered wage losses as a result of COVID-19 can receive up to $600 in financial assistance from the BC Hydro Customer Crisis Fund. In Alberta, the government announced on March 18th that residential customers would be able to defer payment of their electricity and natural gas bills. Also, a 45-day electricity pricing suspension by the time of use for residential customers, businesses, and farm operators. In addition, the relief provided for electricity costs for eligible residential consumers, farms and small businesses is increased by $1.5 billion from the 2019 budget. On May 14th, Newfoundland announced $2.5M in funding to cancel interest on overdue electricity bills for residential and business customers for a 15-month period starting June 1, 2020.

[10] The announcements came particularly quickly in Montreal and Toronto, which also delayed the payment of utility bills. In Calgary, the decision was made on April 16th and about two weeks afterwards in Vancouver.

[11] Governement of Canada, Prime Minister announces more support for workers and businesses through Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, March 18, 2020.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Alberta was the first to announce it on the 18th. One week later, all other provinces had aligned themselves except for Manitoba, where it was announced on April 7th.

[14] Government of Canada, Prime Minister announces more support for workers and businesses through Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, March 18, 2020.

[15] Ibid.

[16] On March 30th, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced a similar measure. In Quebec, on April 29th, the government announced the availability of interest-free loans of $1,500, repayable in August 2021, for tenants whose incomes have decreased. Financial assistance is also available to those who need to postpone their move to their main residence.

[17] The program provides benefits to workers who agree to reduce their work hours due to circumstances beyond the control of their employer, these replace 55% of lost wages.

[18] The details of this compensation were only available on April 29th, with a maximum payment of $500 per week per employee, in coordination with federal assistance.

[19] New Brunswick later announced a working capital loan program (on March 26th).

[20] After March 25th, the property tax deadline was extended by three months in Calgary and 60 days in Vancouver.

[21] From March 23rd (in Alberta) to April 3rd (in Manitoba), WCB premium payments were delayed in all the provinces that had not previously announced it.

[22] Supra note 13.

[23] A further reduction in school tax rates for commercial properties was announced on April 16th, resulting in most businesses getting a 25% reduction in total property taxes.

[24] In addition, the Government has introduced a refundable tax credit (at a rate of 10%, and up to $45,000) for investment in regional development (construction, renovation or purchase of buildings in designated areas).

[25] Government of Canada, Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan: Support for Canadians and Businesses – Backgrounder, March 18, 2020.

[26] As well as not-for-profit organizations and charitable organizations.

[27] Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Office of the Premier, Letter to the Prime Minister of Canada, March 20, 2020. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6823548-Letter-to-Prime-Minister.html

[28] Bank of Canada actions in the days that followed allowed the Government to borrow more than $2 billion to finance its operations. See Newfoundland and Labrador, Urgent Legislative Sitting Supports Social and Economic Well-Being of Newfoundlanders and Labradorians, March 26, 2020. https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2020/exec/0326n03/

[29] The Alberta Government also established an economic council chaired by Jack Mintz to find ways to protect jobs during the economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent collapse of energy prices. The Council will also focus on long-term recovery strategies for the crisis, including efforts to accelerate the diversification of Alberta’s economy.

[30] In Prince Edward Island, the program targeted workers who no longer qualified for employment insurance. The province also introduced a maximum benefit of $1,000, available until June 16th, for those not eligible for any assistance.

[31] The province also announced that for a three-month period, the CERP or EI benefits would not affect the aid delivered through its income support programs.

[32] MyAlberta, Emergency Isolation Support. https://emergencyisolationsupport.alberta.ca/ (page visited on May 26, 2020).

[33] Government of Quebec, Pandemic of COVID-19 – Positive assessment of the implementation of the Temporary Aid for Workers Program, April 9, 2020. https://www2.gouv.qc.ca/entreprises/portail/quebec/actualites?lang=fr&x=actualites&e=4258004408 (Page visited on May 26, 2020).

[34] These workers must earn a gross salary of $550 per week or less, have an annual working income of at least $5,000 and a total annual income of $28,600 or less, calculated before the benefit.

[35] Available for a maximum of 16 weeks, these workers must earn a gross salary of $550 per week or less, have an annual working income of at least $5,000 and a total annual income of $28,600 or less, calculated before the benefit.

[36] This was announced in Alberta and Ontario on April 16th and 25th, respectively.

[37] The announcement was made on April 15th, but it was not until May 7th that the Federal Government confirmed that all provinces and territories had presented, or were in the process of presenting, a cost-sharing plan to improve the wages of their essential workers.

[38] In Prince Edward Island, the program targets essential workers earning less than $3,000 per 4-week period; they will receive a premium of $1,000 per period through their employer.

[39] In Nova Scotia, the program targets employees within the health system, and the program offers up to $2,000 after 4 months of work. In British Columbia, front-line workers in the health-care system, social services and corrections will receive a lump-sum payment of about $4 per hour for a 16-week period, starting on March 15.

[40] That includes the Premiers of Manitoba and New Brunswick, in addition to Quebec. Hélène Buzetti and Marie Vastel, Un employé peut refuser de travailler et toucher la PCU, confirme Ottawa, May 12, 2020, Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/canada/578761/un-employe-peut-refuser-de-travailler-et-toucher-la-pcu-confirme-ottawa

[41] By adding $1,000 per month earned while working part-time to the $2,000 under the CERB, the total income is $3,000; at $20 per hour, an employee must work over 37.5 hours per week to earn more.

[42] The April 9th press release from the Government of Saskatchewan added: “Adjustments may be made to the program once details of any federal assistance are announced.”

[43] Government of Canada, Support for Students and Recent Graduates Impacted by COVID-19 – Backgrounder, April 22, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2020/04/support-for-students-and-recent-graduates-impacted-by-covid-19.html

[44] Eligible students will be able to receive the benefit while earning up to $1,000 per month. Eligible students with dependents or disabilities will receive $2,000 per month, the same amount as the CERB.

[45] For a minimum benefit of 25 hours per week.

[46] On May 5th, Prince Edward Island doubled the grants available to students to encourage them to work in the agricultural sector during the summer.

[47] During debates in the House of Commons on April 29, 2020, when the CESB legislation was passed.

[48] Government of Canada, Prime Minister announces additional support for Canadian seniors, May 12, 2020.https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2020/05/12/prime-minister-announces-additional-support-canadian-seniors

[49] The Government also provides a full refund of certain employer payroll taxes related to the compensation of employees who do not do any work. In Quebec, the Government announced a tax credit for employees on forced leave.

[50] This program has been terminated.

[51] In Newfoundland, a subsidy of up to $3,500 per full-time job is available to help hire students to help seniors and vulnerable people facing social isolation.

[52] British Columbia announced on April 16th that local governments were allowed to borrow interest-free from their reserve funds to finance their operating expenses. Nova Scotia implemented a $380 million municipal loan program. Saskatchewan announced the acceleration of municipal revenue sharing, and Manitoba announced the acceleration of its operating grants to municipalities.

[53] The Newfoundland and Labrador Liquor Corporation introduced various relief measures for local businesses and announced investments to increase the production capacity of small producers. In British Columbia, payment of liquor licence renewal fees has been deferred for most licence holders.

[54] In Manitoba and Newfoundland, other government agencies have announced the return of surplus funds to eligible businesses and individuals. The Manitoba Public Insurance Corporation will redistribute its surplus due in part to a decrease in claims during the pandemic. Insured persons will receive an amount based on payments made last year. In Newfoundland, commercial and residential customers whose electricity rates are based on the fuel costs of the Holyrood Generating Station will receive a variable credit based on their consumption; the expected fuel savings at the plant are therefore provided on an accelerated basis to residential and commercial consumers.

[55] On April 22nd CEBA funding was increased to $41.25B.

[56] Initially, these were companies with a total paid payroll in 2019 of between $50,000 and $1 million. The expansion means that the total paid payroll to be considered must now be between $20,000 and $1.5M.

[57] Particularly through a temporary wage subsidy program for innovative firms that are not yet generating revenue or are in the early stages of development, funded with other measures, through an investment of $250M in the Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP). A sum of $287M in funding was also provided to the Community Futures Network of Canada, as well as $675M to the Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) for businesses not eligible for existing measures, resulting in the creation of the Regional Relief and Recovery Fund.

[58] In Nova Scotia, eligible businesses will have access to a loan (up to $25,000), a grant of up to $1,500 and a contribution of up to $1,500 for consulting services.

[59] Landlords who defer rent payments to commercial tenants whose operations are suspended or limited due to the pandemic may be eligible for coverage (up to $50,000 per landlord and $15,000 per tenant) if are unable to recover the deferred rent amount.

[60] The CMHC website, which administers the program, indicates as of April 30th that they would be working on another mechanism for building owners who do not have mortgage loans. On April 30th, the Prime Minister announced that there may soon be a program for businesses paying monthly rent over $50,000.

[61] Alberta, Provincial response to COVID-19 outbreak, March 29 – April 4. https://www.alberta.ca/release.cfm?xID=70006F59C34A1-DAA3-C970-FA8F91A676395591

[62] Saskatchewan, Provincial Support for Saskatchewan’s Oil Industry, April 14, 2020. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2020/april/14/oil-industry-support

[63] Government of Canada, Prime Minister announces new support to protect Canadian jobs, April 17, 2020. https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2020/04/17/prime-minister-announces-new-support-protect-canadian-jobs

[64] The Government also proposed changes to EI for fish harvesters (self-employed or otherwise).

[65] Such as the cost of possible write-offs of 25% of CEBA loans.

[66] Government of Canada, Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan: Support for Canadians and Businesses – Backgrounder, March 18, 2020.

[67] Government of Canada, Prime Minister announces support for small businesses facing impacts of COVID‑ 19, March 27, 2020. https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2020/03/27/prime-minister-announces-support-small-businesses-facing-impacts

[68] Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, April 9, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-008-S/LEG-2021-008-S_en.pdf

[69] Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, April 28, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-016-S/LEG-2021-016-S_en.pdf

[70] Quebec, Government of Quebec announces new measures to help citizens and businesses, March 27, 2020. http://www.finances.gouv.qc.ca/documents/Communiques/fr/COMFR_20200327.pdf

[71] As well, the deferral of payments by municipalities to school boards amounts to $1.8 billion in Ontario. See Ontario, Ontario’s Action Plan Against COVID-19, March 25, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/mof/fr/2020/03/plan-daction-de-lontario-contre-la-covid-19.html

[72] For example, in the case of the SME joint loan program, which increased the lending capacity of the Business Development Bank of Canada by $20 billion, the PBO calculates a positive financial impact of $389 million. Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-009-S/LEG-2021-009-S_en.pdf

[73] On April 24th, the PBO estimated the cost of the measure at $9.1 billion. See Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, April 24, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-013-S/LEG-2021-013-S_en.pdf

[74] This estimate does not include the impact of the 12-week extension announced on May 15th. On May 28th, the Government of Canada unveiled new estimates of the total impact of support measures, including significant revisions to the estimated cost of the CEWS, which decreased to $45 billion, compared to $73 billion on April 22nd. On April 30th, the PBO estimated the cost of the measure at $76 billion. See Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, April 30, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-018-S/LEG-2021-018-S_en.pdf

[75] Canada, Claims to date – Canada emergency wage subsidy (CEWS), June 2, 2020.

https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/subsidy/emergency-wage-subsidy/cews-statistics.html

[76] The $35 billion estimate was consistent with that of the PBO. See Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Legislative Costing Note, April 30, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/LEG/LEG-2021-019-S/LEG-2021-019-S_en.pdf

[77] As of June 7, 2020, the gross cost of CERB payments to more than 8.4 million Canadians was $44.6B. Government of Canada, Canada Emergency Response Benefit statistics, June 8th, 2020.

https://www.canada.ca/fr/services/prestations/ae/reclamations-rapport.html

[78] These amounts include funds dedicated to support measures for vulnerable groups and the organizations that support them, measures that are not discussed in this text but that have been announced by other provinces, as well as by the Federal Government. In New Brunswick, the government expects the deficit to reach $299.2 million in 2020-21; last March, a budget surplus of $92.4 million was projected. The pandemic and containment measures will result in an estimated $291.4 million drop in revenues, as well as an estimated $100.2 million increase in spending, of which $39.5 million will be offset by increased federal transfers.

[79] Office of the Parliamentay Budget Officer, The PBO’s COVID-19 Analysis, April 28, 2020. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/en/covid-19

[80] An increase of 8.2 percentage points since the Budget unveiled in December 2019. William Hoke, Italian Government’s €55 Billion Stimulus Plan Offers Tax Breaks, Tax Analysts, May 15, 2020. https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-international/budgets/italian-governments-eu55-billion-stimulus-plan-offers-tax-breaks/2020/05/15/2cjfl?highlight=deficit (Retrieved on May 29, 2020).

[81] It was evaluated at 2.4% of GDP in the latest budget forecast. Office for Budget Responsibility, Coronavirus analysis–Policy Monitoring. May 14, 2020. https://obr.uk/download/coronavirus-policy-monitoring-database-14-may-2020/ (Data retrieved on May 29, 2020).

[82] For the fiscal year ending September 30, 2020. In 2019, the deficit was at 4,6% of GDP. Congressional Budget Office, CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021, April 24, 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56335 (Page retrieved on May 29, 2020).

[83] Data from the OECD, Policy response to the COVID-19 crisis, Employment and social policy responses by country, updated as of May 6, 2020.

[84] Data from “Wage Subsidy Benchmarking and Related Measures” updated April 27, 2020 on the Chaire de recherche en fiscalité et en finances publiques website.

[85] Ireland established its COVID-19 Pandemic Unemployment Payment, available to all employees and self-employed workers who lose their income as a result of COVID-19. The program is 12 weeks long and provides access to a uniform payment of €350 per week.

[86] In one of the remaining countries, the date was in March; in three others, the taxes are due in October. Australia and the United States have also allowed the withdrawal of pension funds without penalty.

[87] Data from a “Comparative Analysis of Business Tax Easing Measures” updated May 1, 2020 on the Chaire de recherche en fiscalité et en finances publiques website.

[88] The finding comes from a “Comparative Analysis of Municipal Business Assistance Measures” updated on May 1, 2020, on the Chaire de recherche en fiscalité et en finances publiques website.

[89] An analysis of the response to COVID-19 from sub-national governments in federal states would certainly be useful to compare the response of Canadian provinces, but currently the available data is too fragmented to provide a clear picture of the situation.