John Lester

The federal government has overcompensated Canadians for their lockdown-related income losses. The amount of money involved is substantial. Although overcompensation does not seem to have been a policy objective at the outset, it has been embraced. This expensive flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic compromises fairness and limits options for using fiscal policy to strengthen the recovery.

Canada is going through its most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression in the 1930s. Such a sharp economic contraction would normally result in a substantial decline in household incomes. However, the pandemic-induced recession was accompanied by such generous income support policies that disposable income rose rather than fell: from January to September 2020, real output was down a cumulative 18% but disposable income rose 23%.[1]

The biggest contribution to this outcome came from transfers under the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which by itself exceeded all earnings losses by about $18 billion. Such overcompensation of income losses appears to have been unplanned but nevertheless welcomed by the federal government as a means of bolstering the recovery. In this commentary, I make the case that overcompensation represents a major flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic primarily because of its impact on fairness. Overcompensation also limits options for using fiscal policy to strengthen the recovery.

Income support programs during the pandemic-induced recession

The federal government has acted aggressively to support incomes during the global economic turmoil arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. The CERB was the largest income support program. It provided replacement income to paid workers and the self-employed from March 15 to September 26. The CERB effectively replaced Employment Insurance (EI) for new applicants but existing beneficiaries continued to receive EI payments. The Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) provides replacement income over two years for students and recent graduates who are not eligible for the CERB or EI. The benefit is $1,250 a month. During the March-June period, households also received supplementary payments under the goods and services tax (GST) credit and enhancements to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). These supplementary payments were intended to offset the cost of setting up home offices, buying equipment for home schooling, and making alternative arrangements for daycare. The payments were in addition to the CERB and the CESB for some individuals and were made to others who may not have suffered an income loss or higher costs.

Overcompensation for income losses

Unlike traditional earnings replacement programs, which link the size of benefits to prior earnings, CERB payments were a fixed amount of $500 a week, or $2,000 per four-week application period, for all recipients. Based on a survey of Quebec residents, Achou et al. (table 11) report that CERB applicants suffered an average earnings loss of $1,616 in April 2020; a fixed $2,000 payment therefore resulted in average excess compensation of almost 25%.[2] Two factors mitigated the scale of income losses. First, claimants could earn $1,000 per four-week claim period without affecting CERB benefits. Second, lockdown-related job losses affected low-income earners more severely. Achou et al. show that slightly more than one-quarter of Quebec CERB applicants earned less than $2,000 per four-week period in 2019.[3]

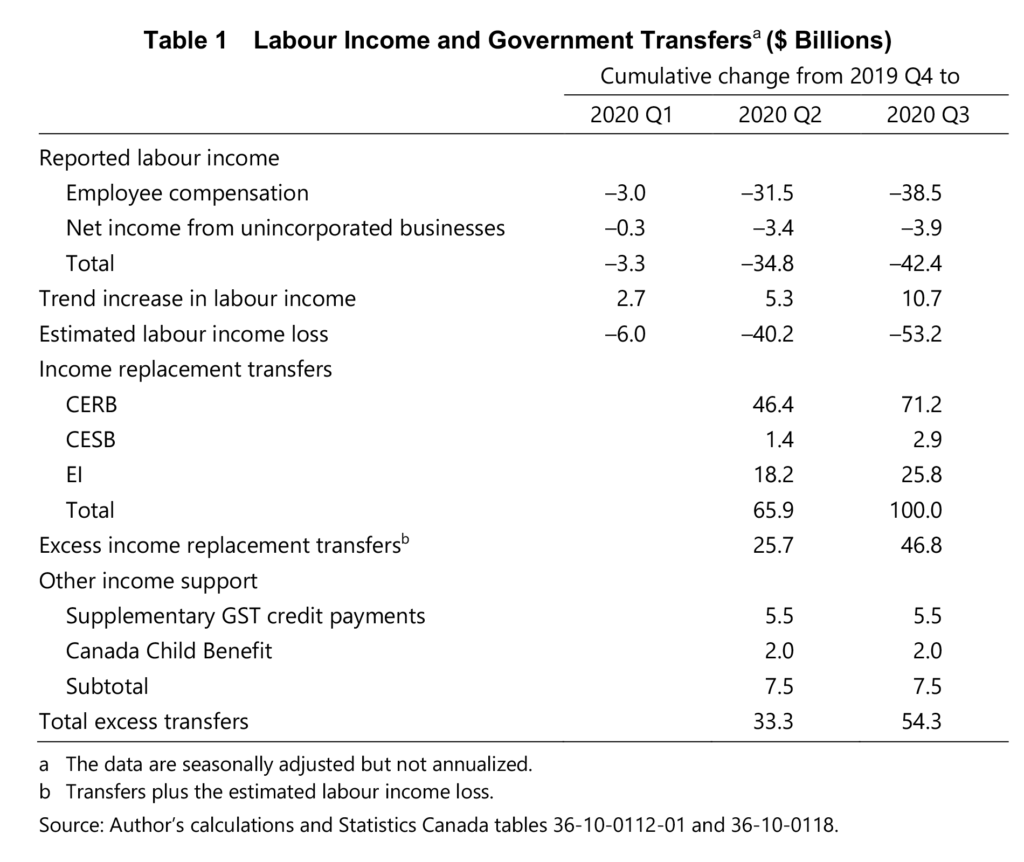

More comprehensive estimates of overcompensation can be developed using data from the national economic accounts; see table 1 below. These accounts show that labour income fell a cumulative $53 billion (actual rate) below its trend value[4] in the first three quarters of 2020. CERB and CESB benefits totalled $74 billion in the second and third quarters, which was just over $20 billion more than the estimated loss in labour income.[5] The economic downturn meant that many EI claimants were unable to find work, so they continued receiving benefits longer than they would have otherwise. In the third quarter, EI benefits were a cumulative $26 billion higher than in the last quarter of 2019. Including EI benefits, income replacement transfers exceeded the cumulative labour income loss by $47 billion. Including the supplementary GST credit and CCB transfers, income supports slightly more than doubled the amount of labour income that has been lost so far during the pandemic-induced recession.[6]

This estimated amount of overcompensation is overstated for three reasons. First, a reduction will occur when 2020 taxes are filed because the CERB and EI payments are taxable. An illustrative calculation suggests that the tax rate on CERB payments will be about 18% at the federal level and about 2.5% in Ontario.[7] If the same rate applies to EI benefits, federal and provincial tax recovery would reduce overcompensation by $20 billion, to $27 billion. Nevertheless, the overcompensation rate – almost $1.90 for each $1 in earnings loss – does not change much if both earnings and transfers are measured after taxes.

Second, eligibility is subject to verification and it is likely that some payments not meeting the prior-income requirements will be found when taxes are filed. In addition, more formal auditing of the programs for ineligible recipients and fraud is also likely to reduce the excess compensation. If unintended payments and fraud account for 5% of CERB and CESB payments, overcompensation would fall by about $4 billion.

Third, the income loss of owners of incorporated businesses is likely too low. Their income consists of wages paid to themselves and, in the longer term, profits earned by the company. Working proprietors may not have reduced their wages by the full amount of the decline in profits. The cumulative decline in corporate sector net operating income so far this year is approximately $95 billion. This estimate includes all non-financial corporations—there is no information by size of firm. However, losses of small businesses primarily owned by working proprietors would have to amount to just over one-third of the total to reverse the finding of net overcompensation.

Policy choice or design flaw?

Overcompensation could have been a deliberate but debatable policy choice or an accidental design flaw. A review of statements, primarily in media releases, made as policies were announced gives no hint that the government set out to transfer more income than necessary to meet ongoing expenses, which suggests that overcompensation resulting from a design flaw was in fact the case. For example, when announcing the top-ups to the CCB and the GST credit and student benefits on March 18, Prime Minister Trudeau was quoted as saying, “Canadians should not have to worry about paying their rent or buying groceries.” When the CERB was announced a week later, Finance Minister Morneau emphasized the need for a speedy response.

In his House of Commons speech tabling the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot (EFS) on July 8, Minister Morneau stated that the three key guiding principles used in setting up the COVID-19 response plan were speed, scale, and simplicity. The decision to make a fixed payment may therefore have been motivated by a desire for speed and simplicity. As documented by Jennifer Robson, timely and comprehensive[8] income support measures meant abandoning the traditional “verify-but-trust” administrative structures in favour of a “trust-but-verify” approach that allowed claimants to affirm eligibility with the understanding that verification could follow at a later date. Tying payments to prior earnings would not have substantially undermined the objective of simplicity and need not have affected timeliness in a trust-but-verify environment: applicants could have self-reported earnings in a previous period subject to later verification.

Although overcompensation does not appear to have been a planned outcome, the government had ample opportunity to adjust the CERB once it became clear that overcompensation was occurring, which suggests that overcompensation was viewed favourably. Finance Canada likely first became aware of the generosity of the CERB shortly after the release of the March Labour Force Survey in early April, which showed how sharply job losses were affecting low-income workers. The CERB was extended with no changes to policy parameters on June 15, from a maximum of 16 weeks to 24 weeks. It is highly likely that Finance Canada had a clear understanding of the extent of overcompensation at that time since an estimate of the amount of overcompensation was included in the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot released on July 8.[9] The CERB was extended for an additional 4 weeks on August 20, with no change to program parameters. Further, the successor programs to the CERB—enhanced access to EI, the Canada Recovery Benefit for persons not eligible for EI, the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, and the Canada Recovery Caregiver Benefit—all feature a minimum payment of $500 a week,[10] which suggests that overcompensation for income losses will be a feature of these programs as well.

The Fall Economic Statement presented on November 30 implicitly defends overcompensation as a means of bolstering the recovery. The generous income support programs contributed to the huge rise in the savings rate, which increased from 2% at the end of 2019 to 27.5% in the second quarter of 2020.[11] The statement describes these additional savings as a “preloaded stimulus that Canadians will be able to deploy once the virus is vanquished and the economy fully reopens” (at 40). Tilting fiscal stimulus toward low-income individuals can be defended on the grounds that they are more likely to spend the transfers—albeit with a lag—than high-income individuals. However, not all low-income earners benefited from overcompensation, so the policy fails a basic fairness test.

Preloading the stimulus is also subject to the criticism that it does not consider how much fiscal stimulus is required. Exactly compensating people for income losses runs no risk of overstimulating the economy, but overcompensation does. The contrast with the plan to carefully assess the need for up to $100 billion in targeted stimulus over the next three years is striking. In contrast to the ad hoc acceptance of overcompensation, the government plans to set up “fiscal guardrails” and use “data-driven” triggers to determine when the planned fiscal stimulus can be wound down.

Overcompensation in the first round of income support measures and a similar outcome in the second round will limit the options that can be considered as part of the government’s targeted stimulus. The fiscal guardrails may come up much sooner than expected, with the result that overcompensation may squeeze out spending that is more highly valued by Canadians.

Concluding remarks

The federal government has overcompensated Canadians for their lockdown-related income losses. The amount of money involved is substantial. Although overcompensation does not seem to have been a policy objective at the outset, it has been embraced. Overcompensation through income replacement programs was about $47 billion in the nine months ending in September. Other transfers to households boosted disposable income by an additional $7.5 billion. This expensive flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic compromises fairness. The economic lockdown caused a loss in income and output that should be shared fairly by Canadians. Fairness is subjective, but few would argue that some members of society—in this case, a subset of low-income earners—should be better off because of the economic lockdown, while others (including some low-income earners) suffer an income loss.

The size of the overcompensation for past income losses and the strong possibility that overcompensation will be a feature of the second round of support measures limit the amount of additional fiscal support needed to ensure a robust recovery. As a result, the government has fewer options for “building back better” and may have made additional fiscal stimulus unnecessary.

[1] Disposable income rose slightly in the 2008-09 recession when real GDP fell almost 5%.

[2] The survey was undertaken in mid-May 2020. There were 3,009 respondents, ranging in age from 25 to 64.

[3] Achou et al. supplied the data points and income thresholds for figure 1 of their study, which shows the distribution of CERB applicants by reported earnings decile. Individuals in the first decile earned less in 2019 than the $5,000 minimum to qualify for the CERB, but small business owners receiving dividends and persons receiving EI maternity or parental leave benefits also qualified.

[4] Trend labour income is assumed to grow 0.83% per quarter in 2020, its average growth rate over the five years ending in 2019.

[5] The $71.2 billion in CERB payments recorded in the national economic accounts is $10.4 billion less than the total payments reported in the Fall Economic Statement (at 44). Some of the discrepancy reflects a lag in processing payments.

[6] This estimate of the overcompensation rate is much smaller than the estimate developed by Patrick Brethour. The estimate in this commentary is based on the cumulative change in employment income and selected government transfers from the last quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2020. Brethour’s estimate is based on the (non-cumulated) change from the first quarter to the third quarter in overall market income and overall government transfers.

[7] The calculation assumes that the distribution of benefits in Quebec reported by Achou et al. applies across Canada; that workers claim the CERB for the full 28 weeks; that workers earn employment income when not claiming the CERB; and that individuals, when filing taxes, claim the basic personal amount, the employment amount, and credits for CPP/QPP and EI. I further assumed that CERB transfers count as income when determining the value of the Canada Workers Benefit and the GST/HST credit. If workers are assumed to claim the CERB for 14 weeks, and to work for 38 weeks, the federal tax rate rises to almost 20% and the Ontario rate rises to 6.5%.

[8] The minister responsible for Employment Insurance testified in Parliament that it would have taken 12 to 18 months to process the EI claims associated with the economic lockdown. In addition, restricting eligibility to EI would have substantially reduced the number of beneficiaries: just over one-third of the unemployed did not qualify for EI in 2018 (Statistics Canada).

[9] The Economic and Fiscal Snapshot (chart 2.17) estimated that from March to June, employees received $10.7 billion more in CERB and CESB transfers than they lost in employment income. The percentage overcompensation is almost 25%. Including the supplementary GST credit and CCB payments, income support for individuals and families from March to June was about $18 billion more than the estimated decline in labour income.

[10] The Canadian Recovery Benefit is subject to a 10% withholding tax and is clawed back at 50 cents for every dollar by which net income exceeds $38,000. Neither of these features affects the potential for overcompensation.

[11] In the downturns of the mid-1970s, the early 1980s, the early 1990s, and the Great Recession of 2008-09, the maximum increase in the household savings rate was about 8 percentage points.

Overcompensation of Income Losses: A Major Flaw in Canada’s Pandemic Response

By adminJohn Lester

The federal government has overcompensated Canadians for their lockdown-related income losses. The amount of money involved is substantial. Although overcompensation does not seem to have been a policy objective at the outset, it has been embraced. This expensive flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic compromises fairness and limits options for using fiscal policy to strengthen the recovery.

Canada is going through its most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression in the 1930s. Such a sharp economic contraction would normally result in a substantial decline in household incomes. However, the pandemic-induced recession was accompanied by such generous income support policies that disposable income rose rather than fell: from January to September 2020, real output was down a cumulative 18% but disposable income rose 23%.[1]

The biggest contribution to this outcome came from transfers under the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which by itself exceeded all earnings losses by about $18 billion. Such overcompensation of income losses appears to have been unplanned but nevertheless welcomed by the federal government as a means of bolstering the recovery. In this commentary, I make the case that overcompensation represents a major flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic primarily because of its impact on fairness. Overcompensation also limits options for using fiscal policy to strengthen the recovery.

Income support programs during the pandemic-induced recession

The federal government has acted aggressively to support incomes during the global economic turmoil arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. The CERB was the largest income support program. It provided replacement income to paid workers and the self-employed from March 15 to September 26. The CERB effectively replaced Employment Insurance (EI) for new applicants but existing beneficiaries continued to receive EI payments. The Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) provides replacement income over two years for students and recent graduates who are not eligible for the CERB or EI. The benefit is $1,250 a month. During the March-June period, households also received supplementary payments under the goods and services tax (GST) credit and enhancements to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). These supplementary payments were intended to offset the cost of setting up home offices, buying equipment for home schooling, and making alternative arrangements for daycare. The payments were in addition to the CERB and the CESB for some individuals and were made to others who may not have suffered an income loss or higher costs.

Overcompensation for income losses

Unlike traditional earnings replacement programs, which link the size of benefits to prior earnings, CERB payments were a fixed amount of $500 a week, or $2,000 per four-week application period, for all recipients. Based on a survey of Quebec residents, Achou et al. (table 11) report that CERB applicants suffered an average earnings loss of $1,616 in April 2020; a fixed $2,000 payment therefore resulted in average excess compensation of almost 25%.[2] Two factors mitigated the scale of income losses. First, claimants could earn $1,000 per four-week claim period without affecting CERB benefits. Second, lockdown-related job losses affected low-income earners more severely. Achou et al. show that slightly more than one-quarter of Quebec CERB applicants earned less than $2,000 per four-week period in 2019.[3]

More comprehensive estimates of overcompensation can be developed using data from the national economic accounts; see table 1 below. These accounts show that labour income fell a cumulative $53 billion (actual rate) below its trend value[4] in the first three quarters of 2020. CERB and CESB benefits totalled $74 billion in the second and third quarters, which was just over $20 billion more than the estimated loss in labour income.[5] The economic downturn meant that many EI claimants were unable to find work, so they continued receiving benefits longer than they would have otherwise. In the third quarter, EI benefits were a cumulative $26 billion higher than in the last quarter of 2019. Including EI benefits, income replacement transfers exceeded the cumulative labour income loss by $47 billion. Including the supplementary GST credit and CCB transfers, income supports slightly more than doubled the amount of labour income that has been lost so far during the pandemic-induced recession.[6]

This estimated amount of overcompensation is overstated for three reasons. First, a reduction will occur when 2020 taxes are filed because the CERB and EI payments are taxable. An illustrative calculation suggests that the tax rate on CERB payments will be about 18% at the federal level and about 2.5% in Ontario.[7] If the same rate applies to EI benefits, federal and provincial tax recovery would reduce overcompensation by $20 billion, to $27 billion. Nevertheless, the overcompensation rate – almost $1.90 for each $1 in earnings loss – does not change much if both earnings and transfers are measured after taxes.

Second, eligibility is subject to verification and it is likely that some payments not meeting the prior-income requirements will be found when taxes are filed. In addition, more formal auditing of the programs for ineligible recipients and fraud is also likely to reduce the excess compensation. If unintended payments and fraud account for 5% of CERB and CESB payments, overcompensation would fall by about $4 billion.

Third, the income loss of owners of incorporated businesses is likely too low. Their income consists of wages paid to themselves and, in the longer term, profits earned by the company. Working proprietors may not have reduced their wages by the full amount of the decline in profits. The cumulative decline in corporate sector net operating income so far this year is approximately $95 billion. This estimate includes all non-financial corporations—there is no information by size of firm. However, losses of small businesses primarily owned by working proprietors would have to amount to just over one-third of the total to reverse the finding of net overcompensation.

Policy choice or design flaw?

Overcompensation could have been a deliberate but debatable policy choice or an accidental design flaw. A review of statements, primarily in media releases, made as policies were announced gives no hint that the government set out to transfer more income than necessary to meet ongoing expenses, which suggests that overcompensation resulting from a design flaw was in fact the case. For example, when announcing the top-ups to the CCB and the GST credit and student benefits on March 18, Prime Minister Trudeau was quoted as saying, “Canadians should not have to worry about paying their rent or buying groceries.” When the CERB was announced a week later, Finance Minister Morneau emphasized the need for a speedy response.

In his House of Commons speech tabling the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot (EFS) on July 8, Minister Morneau stated that the three key guiding principles used in setting up the COVID-19 response plan were speed, scale, and simplicity. The decision to make a fixed payment may therefore have been motivated by a desire for speed and simplicity. As documented by Jennifer Robson, timely and comprehensive[8] income support measures meant abandoning the traditional “verify-but-trust” administrative structures in favour of a “trust-but-verify” approach that allowed claimants to affirm eligibility with the understanding that verification could follow at a later date. Tying payments to prior earnings would not have substantially undermined the objective of simplicity and need not have affected timeliness in a trust-but-verify environment: applicants could have self-reported earnings in a previous period subject to later verification.

Although overcompensation does not appear to have been a planned outcome, the government had ample opportunity to adjust the CERB once it became clear that overcompensation was occurring, which suggests that overcompensation was viewed favourably. Finance Canada likely first became aware of the generosity of the CERB shortly after the release of the March Labour Force Survey in early April, which showed how sharply job losses were affecting low-income workers. The CERB was extended with no changes to policy parameters on June 15, from a maximum of 16 weeks to 24 weeks. It is highly likely that Finance Canada had a clear understanding of the extent of overcompensation at that time since an estimate of the amount of overcompensation was included in the Economic and Fiscal Snapshot released on July 8.[9] The CERB was extended for an additional 4 weeks on August 20, with no change to program parameters. Further, the successor programs to the CERB—enhanced access to EI, the Canada Recovery Benefit for persons not eligible for EI, the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, and the Canada Recovery Caregiver Benefit—all feature a minimum payment of $500 a week,[10] which suggests that overcompensation for income losses will be a feature of these programs as well.

The Fall Economic Statement presented on November 30 implicitly defends overcompensation as a means of bolstering the recovery. The generous income support programs contributed to the huge rise in the savings rate, which increased from 2% at the end of 2019 to 27.5% in the second quarter of 2020.[11] The statement describes these additional savings as a “preloaded stimulus that Canadians will be able to deploy once the virus is vanquished and the economy fully reopens” (at 40). Tilting fiscal stimulus toward low-income individuals can be defended on the grounds that they are more likely to spend the transfers—albeit with a lag—than high-income individuals. However, not all low-income earners benefited from overcompensation, so the policy fails a basic fairness test.

Preloading the stimulus is also subject to the criticism that it does not consider how much fiscal stimulus is required. Exactly compensating people for income losses runs no risk of overstimulating the economy, but overcompensation does. The contrast with the plan to carefully assess the need for up to $100 billion in targeted stimulus over the next three years is striking. In contrast to the ad hoc acceptance of overcompensation, the government plans to set up “fiscal guardrails” and use “data-driven” triggers to determine when the planned fiscal stimulus can be wound down.

Overcompensation in the first round of income support measures and a similar outcome in the second round will limit the options that can be considered as part of the government’s targeted stimulus. The fiscal guardrails may come up much sooner than expected, with the result that overcompensation may squeeze out spending that is more highly valued by Canadians.

Concluding remarks

The federal government has overcompensated Canadians for their lockdown-related income losses. The amount of money involved is substantial. Although overcompensation does not seem to have been a policy objective at the outset, it has been embraced. Overcompensation through income replacement programs was about $47 billion in the nine months ending in September. Other transfers to households boosted disposable income by an additional $7.5 billion. This expensive flaw in Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic compromises fairness. The economic lockdown caused a loss in income and output that should be shared fairly by Canadians. Fairness is subjective, but few would argue that some members of society—in this case, a subset of low-income earners—should be better off because of the economic lockdown, while others (including some low-income earners) suffer an income loss.

The size of the overcompensation for past income losses and the strong possibility that overcompensation will be a feature of the second round of support measures limit the amount of additional fiscal support needed to ensure a robust recovery. As a result, the government has fewer options for “building back better” and may have made additional fiscal stimulus unnecessary.

[1] Disposable income rose slightly in the 2008-09 recession when real GDP fell almost 5%.

[2] The survey was undertaken in mid-May 2020. There were 3,009 respondents, ranging in age from 25 to 64.

[3] Achou et al. supplied the data points and income thresholds for figure 1 of their study, which shows the distribution of CERB applicants by reported earnings decile. Individuals in the first decile earned less in 2019 than the $5,000 minimum to qualify for the CERB, but small business owners receiving dividends and persons receiving EI maternity or parental leave benefits also qualified.

[4] Trend labour income is assumed to grow 0.83% per quarter in 2020, its average growth rate over the five years ending in 2019.

[5] The $71.2 billion in CERB payments recorded in the national economic accounts is $10.4 billion less than the total payments reported in the Fall Economic Statement (at 44). Some of the discrepancy reflects a lag in processing payments.

[6] This estimate of the overcompensation rate is much smaller than the estimate developed by Patrick Brethour. The estimate in this commentary is based on the cumulative change in employment income and selected government transfers from the last quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2020. Brethour’s estimate is based on the (non-cumulated) change from the first quarter to the third quarter in overall market income and overall government transfers.

[7] The calculation assumes that the distribution of benefits in Quebec reported by Achou et al. applies across Canada; that workers claim the CERB for the full 28 weeks; that workers earn employment income when not claiming the CERB; and that individuals, when filing taxes, claim the basic personal amount, the employment amount, and credits for CPP/QPP and EI. I further assumed that CERB transfers count as income when determining the value of the Canada Workers Benefit and the GST/HST credit. If workers are assumed to claim the CERB for 14 weeks, and to work for 38 weeks, the federal tax rate rises to almost 20% and the Ontario rate rises to 6.5%.

[8] The minister responsible for Employment Insurance testified in Parliament that it would have taken 12 to 18 months to process the EI claims associated with the economic lockdown. In addition, restricting eligibility to EI would have substantially reduced the number of beneficiaries: just over one-third of the unemployed did not qualify for EI in 2018 (Statistics Canada).

[9] The Economic and Fiscal Snapshot (chart 2.17) estimated that from March to June, employees received $10.7 billion more in CERB and CESB transfers than they lost in employment income. The percentage overcompensation is almost 25%. Including the supplementary GST credit and CCB payments, income support for individuals and families from March to June was about $18 billion more than the estimated decline in labour income.

[10] The Canadian Recovery Benefit is subject to a 10% withholding tax and is clawed back at 50 cents for every dollar by which net income exceeds $38,000. Neither of these features affects the potential for overcompensation.

[11] In the downturns of the mid-1970s, the early 1980s, the early 1990s, and the Great Recession of 2008-09, the maximum increase in the household savings rate was about 8 percentage points.

Post navigation